Chip-and-PIN Adoption vs. Credit Card Fraud

“The forces of change in the U.S. payments system have never been more plentiful”, Kansas City Fed economists Fumiko Hayashi and Richard J. Sullivan remind us in a recent paper. “Payment card fraud is on the rise. Mobile banking is on the rise. Payments through new social media are swelling. Bank regulations have changed. Lines of competition in the payment card industry have been drawn and redrawn.”

The two economists have focused their attention on two “separate areas of change” — crime and competition. More specifically, Hayashi and Sullivan have looked into the evidence for fraud trends in countries where computer-chip cards have been adopted and have examined the proposition that recent debit card regulations will promote competition for merchants within the payment card industry, as well as the effects of regulations on consumer welfare and payments system efficiency. For my part, I will focus on the authors’ findings on the link between EMV adoption and fraud. Let’s take a look at what they have to tell us.

The Case for U.S. Adoption of EMV

The transition in the U.S. from the older magnetic-stripe technology to the chip-based EMV, known as chip-and-PIN in the U.K. has already begun, but will take years to complete, as both the payment cards we carry in our wallets will have to be replaced and the point-of-sale terminals will need to be retrofitted or (more likely) replaced to be able to become compatible. Once the switch is complete, “[t]he fraudsters, phishers, hackers, and pickpockets who thrive off payment card fraud may… have their work cut out for them”, Hayashi and Sullivan predict. “Compared with the magnetic-stripe cards carried by millions of consumers”, the authors remind us, “the new chip cards will offer stronger defenses against fraud. But they certainly will not put an end to it.” The authors warn against “any prolonged accommodation of older card technology during a transition to computer-chip cards”, for it can “allow fraudsters to exploit weak links in security.”

Another reason for the U.S. to quicken the pace of the transition is that, as Douglas King from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta told us more than a year ago and then a Europol report confirmed his findings several months ago, once they realized just how difficult it had become to commit credit card fraud in Europe following the wholesale EMV adoption, fraudsters decided to take the stolen European cards to the U.S. and take advantage of the older mag-stripe technology while it’s still the norm there. Here is the essence of the Europol report:

Payment card fraud is a low risk and highly profitable criminal activity which brings organised crime groups originating from the EU a yearly income of around 1.5 billion euros. These criminal assets can be invested in further developing criminal techniques or can be used to finance other criminal activities or start legal businesses.

The EU is increasingly exposed to the threat of illegal transactions undertaken overseas and should develop more efficient solutions to help law enforcement authorities (LEAs) combat the fraud.…

The majority of illegal face-to-face card transactions (skimming-related) affecting the European Union take place overseas, mainly in the United States.

So the case for switching to EMV seems compelling.

The U.K. Experience

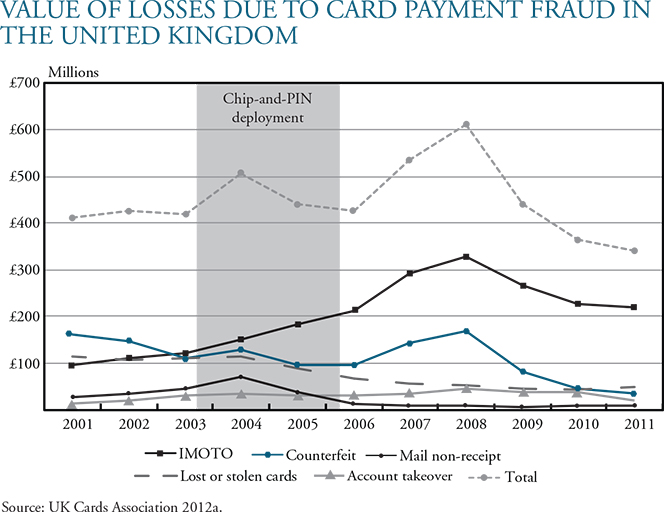

Hayashi and Sullivan have looked into the experience of the U.K. — one of the first countries to make the transition to EMV and concluded that “[t]he benefits of the computer-chip cards were apparent as early as 2005 when fraud losses due to lost or stolen cards began to decline (see Chart 1). Both the added fraud protection due to the computer-chip and the required use of a PIN for transactions successfully limited the ability of anyone who possessed a lost or stolen card to create a fraudulent payment.”

However, the two economists second King’s findings for the spillage effect, noting that, following EMV adoption, “payment fraud soon migrated to channels in the UK with weaker authentication, such as cards still using magnetic stripes and purchases made over the Internet, mail order and telephone order (IMOTO) purchases. For backward compatibility, during the transition period, new computer-chip cards had both computer chips and magnetic stripes. Fraudsters could then make counterfeit magnetic-stripe payment cards and use them wherever merchants or ATMs still accepted the cards, especially outside the UK [read U.S.]. As a result, fraud losses on counterfeit cards in the UK grew from £97 million in 2005 to £170 million in 2008. The move to computer-chip payment cards also left authentication unchanged for IMOTO transactions, making them another attractive outlet for fraudsters. Fraud on IMOTO transactions grew rapidly, from £183 million in 2005 to £328 million in 2008.”

In the years after 2008, fraud declined due to two factors, Hayashi and Sullivan tell us. To begin with, a wider EMV adoption in Europe sharply reduced the number of locations where counterfeit cards could be used. Secondly, merchants in the U.K. increasingly began to adopt “3D Secure Systems”, which are developed by Visa and MasterCard and offered to customers and merchants as the Verified by Visa and MasterCard SecureCode services. “In 2007”, the authors inform us, “only 25 percent of respondents to a survey of UK Internet merchants reported that they accepted 3D secure payments, but the same survey found at least 59 percent of respondents accepted 3D secure in 2011. Total fraud losses on payment cards in the UK fell significantly, from a peak of £620 million in 2008 to £321 million in 2011.” Now, it should be said that, from a merchant’s perspective, the use of a 3D Secure-type of a credit card processing service carries a very significant disadvantage in the shape of an excessively high ratio of declined transactions and it is far from clear whether the trade-off is worth it. Still, as far as fraud alone is concerned, 3D Secure does work.

The Takeaway

Hayashi and Sullivan are cautiously optimistic for the implications for U.S. payment card fraud of what is going to be a years-long transition to EMV:

As the United States begins its transition to computer-chip payment cards, the country will reap the benefits of the dynamic data authentication processes that are not possible on magnetic-stripe cards but can be performed by computer-chip cards. The chip cards are also much harder to counterfeit. Some sources of payment fraud, such as counterfeit cards, will decrease. However, the experience in the UK and other countries also shows that other sources of fraud are likely to increase. Thus the prospects for reducing overall card payment authorization protocols continue, such as signatures for card payments rather than PINs, the degree of fraud reduction that can be achieved will be limited. Similarly, unless authentication protocols are improved for IMOTO transactions, such transactions will become a weak link in the defenses against fraud, and IMOTO fraud will likely increase.

The payment industry must also be alert to new forms of fraud as attackers probe for security weaknesses and exploit them. Fraudsters have strong incentives to commit payment fraud and will continue to test security measures and sometimes defeat them. Card issuers, in turn, will need to reevaluate their choices of authorization and authentication methods periodically, as new trends in fraud emerge.

Image credit: Chipandpin.co.uk.