Why the Debit Interchange Limit Is Especially Bad for Low-Income Consumers

We have previously elaborated in some detail on our view that the recent Federal Reserve rule limiting the amount of fees issuers can charge merchants for accepting their debit cards for payment, known as interchange fees, ultimately hurts consumers. We wrote that, in order to make up for lost revenue, banks will start “creating new or expanding existing revenue sources.” That process, which began before the rule was even finalized, is now manifesting itself in the elimination of free checking accounts, the introduction of new bank fees and the increase of old ones, the slashing of rewards and, my personal favorite – the charging a fee for simply having a debit card.

But there is something else that I’ve been meaning to touch on for some time and it is that the brunt of this new bank revenue-generating push will be borne disproportionately by those who can least afford it — low-income households. Let me explain.

Debit or Credit: It Is Largely Determined by Your Income

According to a recent article by Federal Reserve Bank of Boston researchers Benjamin Levinger and Michael A. Zabek:

[L]ow- and moderate-income consumers tend to use debit cards much more often than they use credit cards. LMI consumers are more likely to own a debit card than a credit card, they are nearly twice as likely to use one for a given transaction, and in general, they tend to rate them as being better payment instruments. This fact should be an important consideration for everyone who works with credit or debit cards.

Levinger and Zabek then proceed to offer some data:

More than 75 percent of LMI consumers have a debit card, whereas only 62 percent have a credit card. Higher-income consumers are more likely to have a credit card. In fact, 90 percent of higher-income consumers have a credit card, and 84 percent have a debit card.

LMI consumers’ preference for debit cards over credit cards is also reflected in how often they use their cards. A look at the volume of debit and credit card payments as a percentage of total monthly payments shows that LMI consumers use debit cards for 29 percent of their payments, whereas they use credit cards for only 13 percent. Higher- income consumers also use debit cards more frequently than credit cards, but the difference is much smaller (27 percent versus 24 percent). (See “Shares of All Payments Made with Credit and Debit Cards.”) Interestingly, debit card payments make up a larger share of all payments for LMI consumers than for higher-income consumers.

Levinger and Zabek then delve into the reasons for the lower-income consumers’ preference for debit cards, but the point is that they do rely on them much more heavily than their more affluent counterparts.

Why not Switch to Credit Cards?

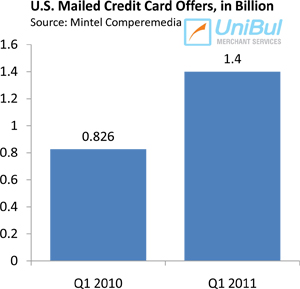

So, if debit card usage is becoming more expensive, why not switch to credit cards? After all, credit card offers are now more numerous and attractive than they’ve been in a long time and anyway, we are told, issuers are already trying to steer customers away from using debit and into credit. Moreover, the CARD Act now ensures consumer protection against unfair practices used by card companies.

So, if debit card usage is becoming more expensive, why not switch to credit cards? After all, credit card offers are now more numerous and attractive than they’ve been in a long time and anyway, we are told, issuers are already trying to steer customers away from using debit and into credit. Moreover, the CARD Act now ensures consumer protection against unfair practices used by card companies.

Well, for one thing, there is the issue of perception. To begin with, Levinger and Zabek tell us that LMI consumers “strongly prefer the setup, security, and control of debit cards,” in addition to perceiving them as less costly to use than credit cards. As the researchers point out, these perceptions are not always well founded, but they are there.

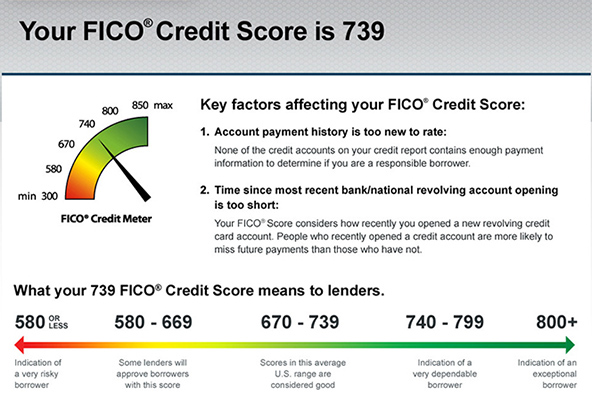

Additionally, even as credit card offers are on the rebound, most of them go to consumers with high credit scores, which also tend to be more affluent.?áNot to mention that LMI consumers are virtually excluded from offers containing incentives (sign-up bonuses, promotional interest rates, etc.).

Then there is also the not-too-trivial issue of managing credit, which can be a daunting task for income-constrained consumers.

So switching to credit, even if it were genuinely available as an option, may not necessarily be more advantageous for LMI consumers than sticking to debit.

The Takeaway

The age of no-fee checking is behind us and we need to adjust to the new reality. In the short run issuers will be testing various debit-related fees, until they identify the ones that work best, both in generating revenue and in least antagonizing customers.

This adjustment process will be more difficult for low-income consumers, as they have at their disposal fewer means for coping with changing financial circumstances, than more affluent Americans. Yet, there are things that can be done and above all, you should pay attention to the terms and conditions of using your debit card and checking account. Often there are provisions for avoiding particular fees, if you comply with certain requirements. For example, my Bank of America checking account is free if I use my BofA credit card at least once a month or if I maintain an average daily balance of $5,000 (otherwise it costs me $15). As a result, I make it a point of using my credit card once a month. Make sure you know these provisions and take advantage of them, when possible.

So do yourself a favor and read all of the letters your bank sends you before throwing them away. You just may save yourself a few bucks (not to mention the nagging feeling that you’ve been taken advantage of) in the process.

Image credit: Larepublica.co.