What the Debit Card Interchange Fee Reform Has Achieved

A recent paper by Fumiko Hayashi from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City is examining the current state of the debit card market and is looking into how that market was shaped by the legislative changes that were introduced over the past couple of years. The interventions by Congress and the Justice Department, the author reminds us, were intended to “advance consumer welfare by promoting competition within the payment card industry”. An admirable objective, to be sure, but was it achieved?

Well, though Hayashi can’t quite bring herself to say it, the answer to this question seems quite clear. On the one hand, merchants have certainly benefited hugely from “new rules [that] cap certain fees” and make it easier to “choose among rival card networks”. Card issuers, on the other hand, have lost billions of dollars of debit interchange revenues, which, the author points out, could cause consumers to “see rewards programs vanish and may face higher banking fees as their banks try to offset lost revenue“. Well, as Hayashi herself acknowledges, that’s already happened. So consumer welfare has certainly not been well served. But let’s take a look at the data Hayashi has compiled for us.

Changing Incentives and Increased Competition

Here is how Hayashi summarizes her findings:

A detailed review of how the new rules have affected card networks and banks—and how they have begun to respond—shows that fee structures have adjusted, incentives within the industry have shifted, and the market shares of the top card networks have changed. Early signs suggest the interventions achieved some of their intended purpose, fostering increased competition in some areas of the industry. But whether the broader public reaps benefit in the long run will depend, in part, on the results of new revenue-generating strategies adopted by key players in the industry.

I would add that any benefit-reaping by the public would also depend on the legislators not forcing said key players to introduce new fees and on the merchants’ willingness to share some of the windfall with their customers, but that is by the by. Now here are the data.

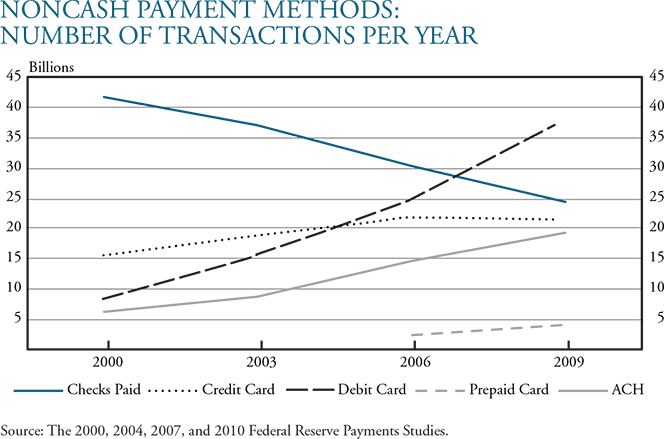

The Rise of Debit

This chart is striking. Also, note that ACH payments, whose share is also on the rise, are very much like debit card payments — the funding source (the user’s checking account) is the same and the only difference is the set of numbers you provide at the time of the transactions.

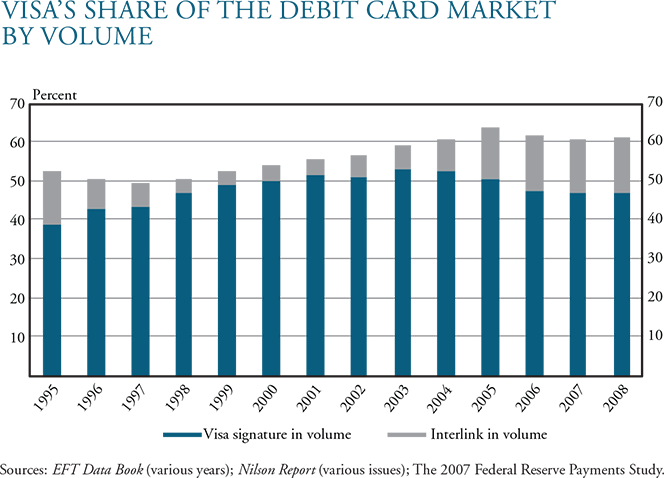

Visa’s Domination

Visa has always owned the dominant share of the U.S. debit card market, Hayashi tells us. Based on transaction volume, Visa’s share of the debit market — the sum of the signature and PIN transaction components — has been greater than 60 percent since 2004, we learn.

Moreover, Visa also owns more than 60 percent of the market when measured in terms of transaction value.

Top Debit Issuers: Bank of America, Wells Fargo, and JPMorgan Chase

On the debit card issuing front, three big banks — Bank of America, Wells Fargo, and JPMorgan Chase — have been the dominant players since 2008 when each one of them gobbled up another large debit card issuer (Merrill Lynch, Wachovia, and Washington Mutual, respectively). Together, these three banks accounted for 39 percent of the market in 2008, measured by debit card transaction value, falling slightly to 37 percent in 2010. U.S. Bank ranked a distant fourth.

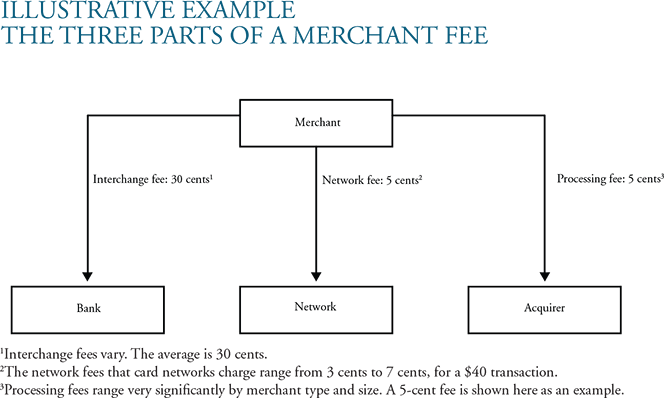

Merchant Fees

Now we come to the most interesting part. Between 2000 and 2009, debit card use — measured by transaction volume — grew by a factor of 4.75 — from 8 billion to 38 billion. Even as the volume spiked, Hayashi tells us, so did the processing fees charged to merchants. Between 2004 and 2010, processing fees charged on signature debit purchases increased from an average of 1.39 percent of the transaction value to 1.85 percent. The corresponding numbers for PIN debit purchases were 0.61 percent and 0.72 percent.

Now, debit processing fees are made up of three components, collected by the debit payment network, the card issuer and the payment processor. By far the largest of these constituents is the fee collected by the card issuer — the interchange fee. Here is a sample breakdown:

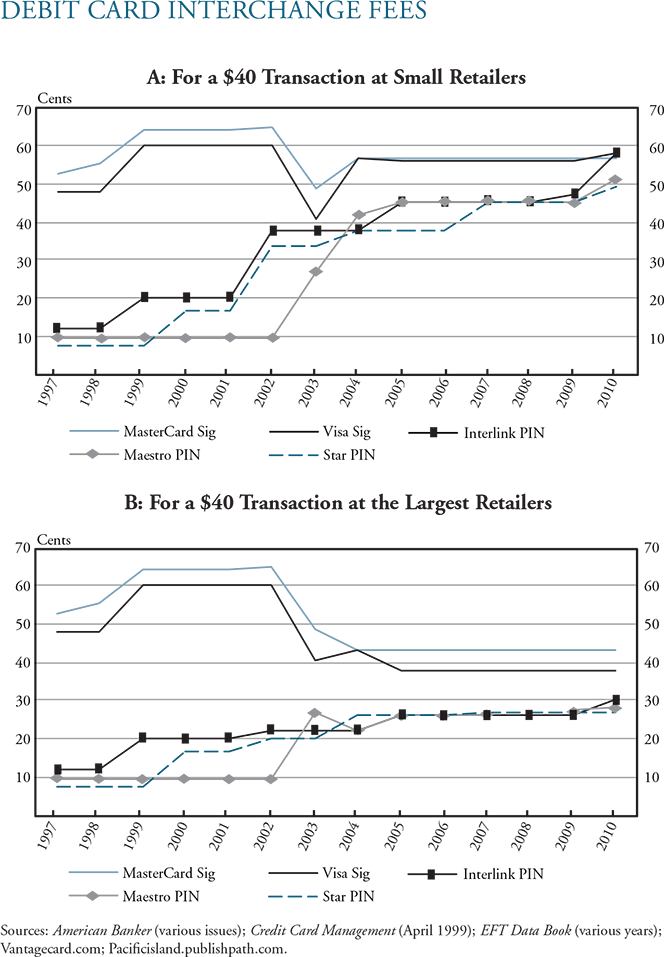

The Durbin Effect

Hayashi offers a striking comparison of the pre-Durbin debit interchange fees paid by “small retailers” and “the largest retailers” (no definitions are given). Here it is:

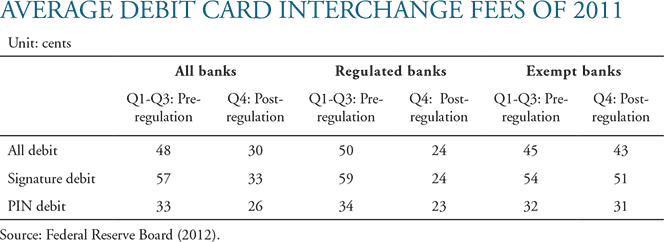

Then, in June 2011, the Federal Reserve, acting on a mandate received from the Durbin Amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act, limited the size of the debit interchange fee that can be collected by banks with assets of $10 billion or more to a maximum of 21 cents per transaction plus 0.05 percent of a transaction’s amount, plus one cent for certified fraud-prevention programs. Smaller banks were exempted from the new rule. Hayashi tells us that “in the fourth quarter of 2011, the regulated banks were collectively generating 67 percent of the country’s signature debit transactions and 60 percent of its PIN debit transactions, for a combined total of 64 percent of all debit card transactions”. Here are the numbers:

Ban on ‘Network Exclusivity’

As already noted, the Durbin Amendment also sought to make the payment processing field more competitive. Here is the measure that was meant to achieve that objective:

Regulation II [the Durbin Amendment] also seeks to ensure that merchants will have some degree of freedom to choose among networks. It does this through its provision that prohibits “network exclusivity” arrangements, requiring all banks to make at least two, unaffiliated networks available for processing the transactions of any given debit card. Under this rule, a bank may comply by having two networks available for signature debit, or by having two networks available for PIN debit, or by having one network available for signature debit and a second, unaffiliated one available for PIN debit.

A choice of multiple PIN debit networks was always made available by most processors I know of, but here it is, anyway.

The Takeaway

Hayashi goes into further details to illustrate the effect the Durbin Amendment had on debit card networks and banks, but more interesting is her account of the varied issuers’ responses to the reduction in interchange revenue:

The regulatory changes have prompted a variety of responses by regulated banks, ranging from the termination of debit card rewards programs to the introduction of new monthly fees either for debit cards or for checking accounts. Some community banks and credit unions, exempt from the interchange fee cap, have reacted to the larger banks’ moves by going in the opposite direction: introducing new rewards for debit card purchases or for opening checking accounts—and in some cases these smaller banks have gained a significant number of new checking account customers.

Yet, the trend quickly tapered off and it is doubtful whether the smaller banks will be able to hold on to the gains they’ve made. And anyway, the huge numbers of consumers who do remain big-bank customers will still suffer the consequences of the Durbin Amendment.

Image credit: Flickr / MoneyBlogNewz.

nice