What Does the Future of Virtual Banking Look Like?

That is the question tackled by The Economist in a recent article and Accenture — a consultancy — in a new paper. And it is a very fashionable topic, one that is only likely to attract ever more interest in the coming years. Both The Economist and Accenture note — and this is the generally-accepted view — that a revolution is under way that is transforming the way banking is done. Accenture predicts that “by 2020 an estimated 15 percent of traditional banks’ revenues could shift to online-only players, including branchless banks and new technology entrants”. That is huge and yet it may well turn out that the researchers’ prediction falls short of the real figure.

But the more interesting question, to me at least, is who stands to benefit the most from the ongoing banking revolution. Well, here too the views of The Economist and Accenture converge. On the one hand we have a host of nimble start-ups, like Simple, which are flooding the digital banking space, signing up huge numbers of very active users under the banks’ very noses. At the same time, the traditional players already have millions of users who, as The Economist reminds us, tend to stay put. Moreover, the barriers to replicating digital banking technology are low, which means that the cool new apps developed by Simple and other start-ups can be (and often are) quickly copied by banks.

Naturally then, both reports conclude that a winning strategy would involve some kind of a merger of the strengths of the two sides of the conflict. The most likely scenario — and the one outlined in The Economist’s piece — would involve the acquisition by an established player (BBVA, Spain’s second-largest bank, in the article’s example) of a promising upstart (Simple, in the same example).

But isn’t it possible that a well-capitalized start-up may be able to take on the banks on its own and succeed? Well, it is certainly not impossible: PayPal did it a decade and a half ago in the payment processing space and Square is now following in its footsteps (although Jack Dorsey’s start-up may now be in trouble). Yet, these two names (one and a half, really) have all but depleted our list of success stories on the scale we are discussing here. Moreover, there isn’t a purely banking start-up that I know of, which is anywhere close to being as well-capitalized and ambitious as the two just mentioned. So, with that in mind, let’s take a look at how a winning combination would look like.

Simplifying Banking

So, The Economist tells us that BBVA, a bank with ?é¼607 billion in assets and 50 million customers worldwide (its U.S. operations are run through Compass, a subsidiary) “believes that traditional banks will soon lose their monopoly on banking”. And lest the implications were somehow lost on people, its chairman warned in The Financial Times last year that “banks faced certain death unless they took on the likes of Amazon or Google”. Well, if you hold such believes, you are highly likely to take bold defensive actions and in BBVA’s case these took the shape of a $117 million acquisition of a fast-growing virtual rival — Simple.

And Simple, The Economist tells us, has had quite a lot to sell. Not only did the start-up have 100,000-strong (and young) user base, which had grown by 330 percent in a year, but its services were heavily used. Its clients, we are told, log into their accounts 2.4 times a day, compared, as the article reminds as, to “the mere handful of interactions most customers have with bank branches in a year”. But there is more:

[Simple’s] app allows users to work out how much it is “safe to spend” instead of simply providing a current balance. And it allows them to extract complex information easily by asking, for instance, how much they had spent on coffee and taxis in New York over the past month.

But didn’t we just mention that, cool though they may be, such apps are incredibly easy to replicate? So why wouldn’t BBVA just copy the thing, rather than spend so much money on buying it? The Economist’s explanation:

Time may be one factor. Another may be culture. Carlos Torres, head of BBVA’s strategy and corporate development, says it is hard for a large organisation to replicate the entrepreneurial talent of an upstart.

I agree. Crucially, however, the pesky, Simple-like, start-ups have a rather big weakness of their own: they don’t quite know how to translate their fast-growing user base into profits. Not to mention that, as they themselves are not regulated as banks, they need one to move their users’ money around anyway. So, yes, this seems to be a match made in Heaven.

The Way Forward

More personalized service and faster problem resolution are the key reasons for switching banks, cited by the respondents in Accenture’s survey. Well, these happen to be the capabilities at which the best digital banking innovators excel. What makes them so good at this is their usage of Big Data and analytics, which help them learn what their customers want — “often before the customer does”. The best virtual banking services “can anticipate customer needs and engage with them to fulfill those needs in real time”. Here is how Accenture’s report puts it:

Digital, in short, is critical to the more agile and innovative operating model that traditional providers now also require. They can invest in digital to transform their IT platforms, overcoming rigid legacy technology in the back office. They can also power an analytics-driven front office, equipped with deeper understanding of customer needs and thus able to develop a more compelling product set — especially for the high-margin products that customers currently seek from others.

Positioning more products in digital channels can also help make operating costs both lower and more flexible. And it can cut distribution costs, just as it has in the retail industry2. Digital banks will spend less on new account acquisition, and new, digital accounts will, in turn, generate more sales.

The digital model can also improve branch performance. Digital channels allow banks to track customer transaction experiences, for example, including at the branch. And the cost advantages of investing in digital channels can be re-invested in upgrading branches. Digital, furthermore, can complement the cross-selling opportunities that are currently being lost at the branch.

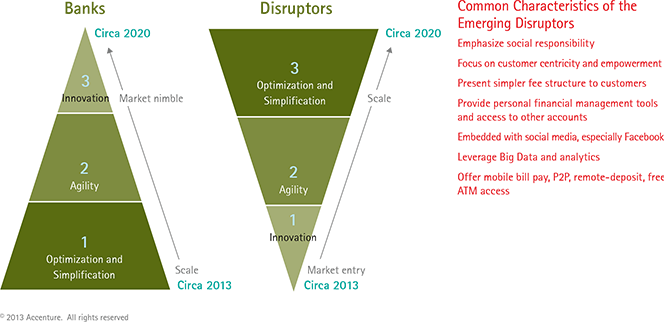

Here is Accenture’s representation of the advantages the best new virtual banking services have over their traditional rivals:

Looked from that angle, it seems inevitable that the traditional banks will keep buying up the digital upstarts and avail themselves of all the nifty new tools — Big Data, analytics, etc. — that make the newcomers so successful.

The Takeaway

It is quite clear, in my mind at least, that for the traditional players, the road to success in the bold new digital banking world goes through the adoption of the technologies that are now feverishly being developed by their new virtual-only rivals. That could be achieved through internal development or, which is more likely to be the case, through acquisitions.

The far more interesting question, however, is whether or not we will see a PayPal-like, independent digital banking champion to emerge from the fray. And there is a lot of interest in building such an outfit. As The Economist tells us, one venture capitalists has remarked that he is “dying to fund a disruptive bank”. There can be little doubt that plenty of start-ups have the ambition to do so. Whether they’ll be able to turn that ambition into reality is yet to be seen.

Image credit: Simple.