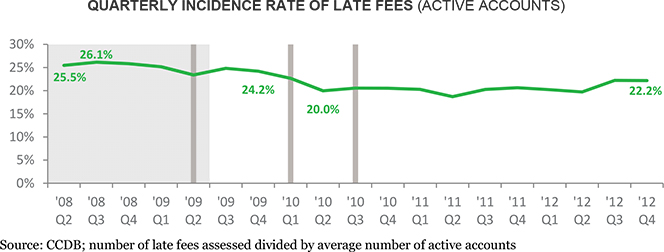

The CARD Act Has Made Credit Cards Cheaper

Earlier this week I reviewed a new NBER paper, which had found that the limits on credit card fees imposed by the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure (CARD) Act of 2009 have reduced Americans’ overall borrowing costs by 2.8 percent of their average daily balances, saving us $21 billion a year in the process. In fact, the same conclusion was reached by the American Bankers Association (ABA) in a newly-released report, which I reviewed last week.

Well, not to be undone, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has just released its own report on the matter, concluding that the CARD Act has indeed had a hugely beneficial effect to American consumers. The CFPB has found that the total cost of credit cards has declined by almost two percentage points between 2008, the last full year before the Act’s gradual implementation began, and 2012. The Bureau’s report is much longer than the other two and there is a lot to go over, but I will only focus on its examination of the movements of the various categories of credit card fees.

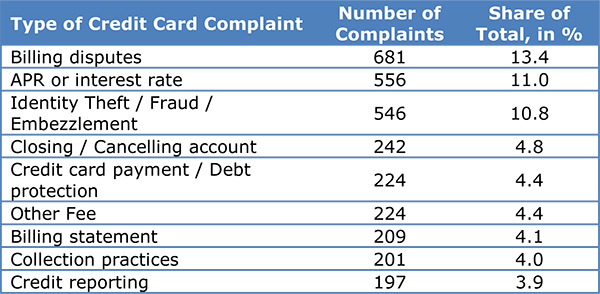

CARD Act Eliminates Over-the-Limit Fees

The CFPB notes that the CARD Act has been directly responsible for the virtual elimination of over-the-limit (overlimit) fees as a source of cost to consumers and revenue to issuers. During the period between the mid-1990s and 2005, the fees charged for over-the-limit transactions had more than doubled, increasing from under $15 to over $30, we are reminded. The CFPB has calculated that, by 2008, the average over-the-limit charge was $34.80.

Then the CARD Act required that over-the-limit fees are “reasonable and proportional” to the violation. Lest anyone wondered what that meant in practice, the Act spelled it out for the issuers: caps were placed on the over-the-limit charges: $25 for a first violation and $35 for each subsequent violation within the next six months. Most credit card issuers responded by simply discontinuing over-the-limit fees altogether. The upshot was a sharp reduction in the over-the-limit incidence rate, as shown in the chart below.

Had the over-the-limit incidence rate remained at 2007 levels and had its average amount remained at its 2008 level, consumers would have paid $2.5 billion more in over-the-limit fees in 2012 than they actually paid, the CFPB has calculated.

Late Fees Go Down

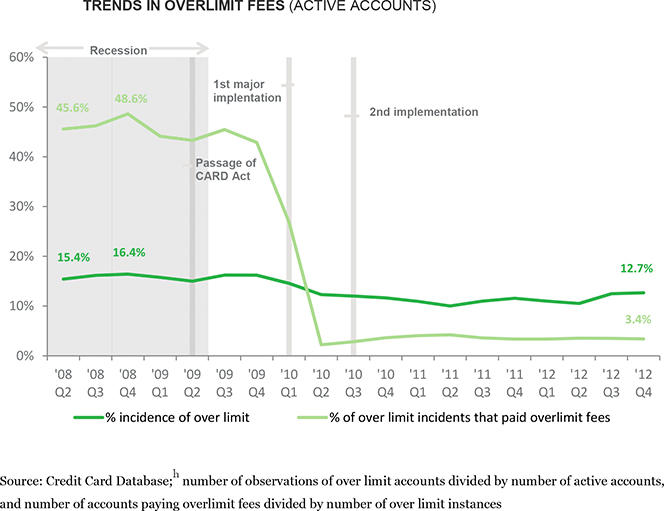

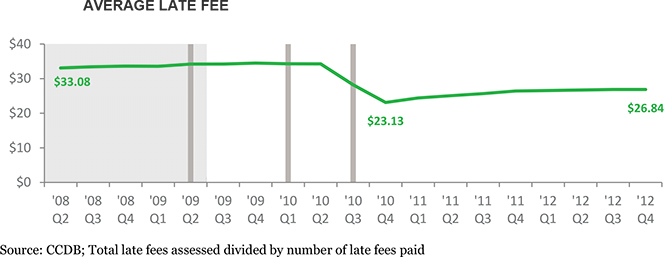

The Act has also caused the dollar amount of late fees to go down. Similarly to over-the-limit fees, the level of late fees rose sharply between the mid-1990s and 2005 — from under $15 to over $30. The CFPB has calculated that the average late fee in 2008 was $33.08.

Then the CARD Act restricted the circumstance under which late fees could be charged. For example, a payment could no longer be considered as late if the payment due date fell on a day on which the issuer did not receive or accept payments by mail (e.g. weekend or holiday) and the payment was instead received on the next business day after the due date. Furthermore, the Act required that the payment due date be on the same day each month, that the billing statements be mailed at least 21 days before that due date and that the statements include a warning of the amount of the late fee and any penalty rate that will be assessed if a payment is late. Finally, the “reasonable and proportional” rule also applied: $25 for a first violation and $35 for each subsequent violation within the next six months. As a result, as seen in the chart below, the average late fee fell from $33.08 in 2008 Q2 to $23.13 in 2010 Q4. By the fourth quarter of 2012, the average late fee had increased by $3.71, reaching $26.84, but it’s still well below pre-Act levels.

The Bureau calculates that the $6 decrease in the average late fee has saved American consumers a total of $1.5 billion. Furthermore, the incidence of late fees has fallen from a high of 26.1 percent in Q3 2008 to a low of 20.0 percent in 2010 Q2, although it had increased to 22.2 percent in 2012 Q4, where it has remained since then.

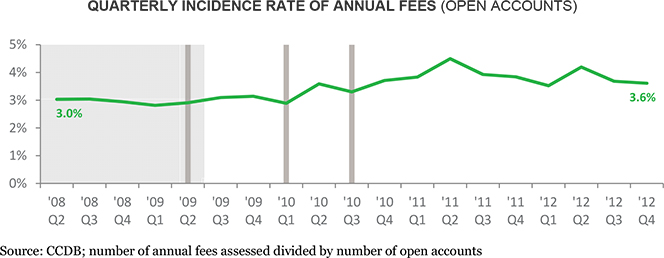

Annual Fees Go Up

The CFPB has also looked into the annual fees and has found that these have increased slightly — from an average of $32.48 in 2008 to $34.19 in 2012 — which has cost American consumers an additional $475 million in annual fees in the latter year.

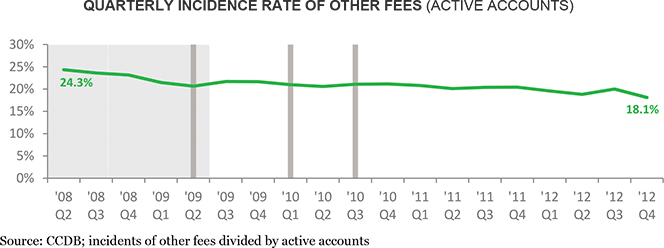

Other Fees Down by $3.5 Billion Annually

However, the increase in annual fees has been more than offset by a decrease in the “other fees” category, which includes charges for debt suspension (these make up about 45 percent of all “other fees”), balance transfers (25 percent), cash advances (20 percent), returned payments and other transactions. The other fees have declined from $2.0 billion per quarter in 2008 to $1.1 billion per quarter in 2012, for an annual decrease of more than $3.5 billion. I think I may take a closer look into this category in a future post.

The incidence rate of other fees has also declined quite substantially: from 24.3 percent in 2008 Q2 to 18.1 percent in 2012 Q4.

The Takeaway

Unsurprisingly, given all the data, the CFPB’s assessment of the CARD Act’s effectiveness is quite positive:

The end result is a market in which shopping for a credit card and comparing costs is far more straightforward than it was prior to enactment of the Act. Many credit card agreements have become shorter and easier to understand, though it is not clear how much of these changes can be attributed directly to the CARD Act since it did not explicitly mandate changes to the length and form of credit card agreements. Limitations on “back-end” fees, along with restrictions on an issuer’s ability to raise interest rates, have simplified a consumer’s cost calculations. Credit card costs are now more closely related to the clearly disclosed annual fees and interest rates. This greater transparency means a consumer deciding whether to charge a purchase can now make that decision with far more confidence that costs will be a function of the current interest rate rather than some yet-to-be determined interest rate that could be reassessed at any time and for any reason by the issuer.

Image credit: Flickr / GuySie.