On Russian Beeznessmen, Fear, Despair, Safes and $100 Bills

A couple of weeks ago, The Washington Post’s Zachary Goldfarb was musing over the fact that our increasing usage of virtual money — credit and debit cards, Square-like services and other types of mobile payments, PayPal, etc. — has failed to slow down the proliferation of paper money. On the contrary, in recent years the quantity of greenbacks in circulation has been growing at an accelerating rate. How could that be? Well, Goldfarb’s explanation is that the trend is driven by fear — people in the U.S. and abroad stuffing their mattresses with $100 bills, because they don’t trust the banks. Then Paul Krugman weighed in, offering a different — and I think more plausible — explanation. The mattress-stuffing exercise, Krugman argued, is motivated by despair — people have nothing better to invest in.

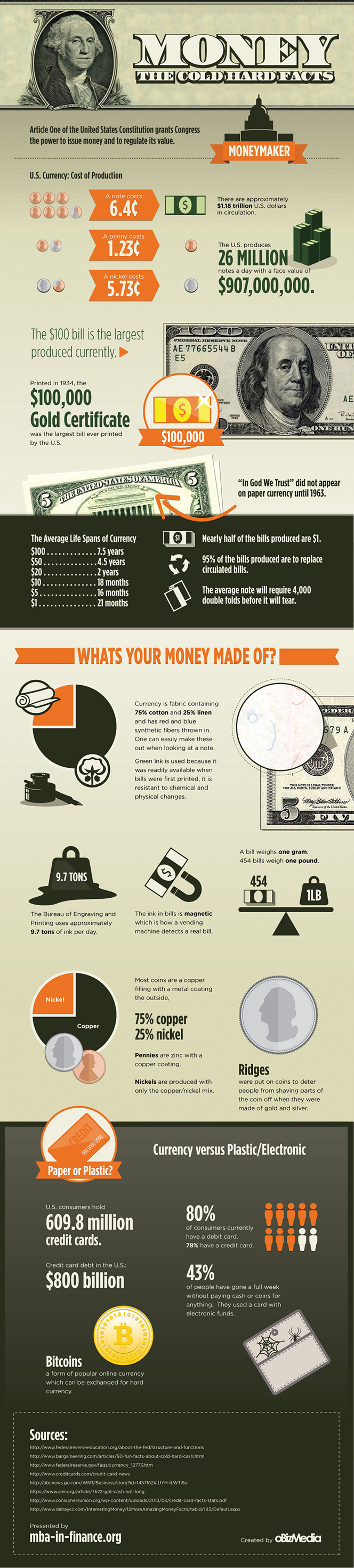

This morning I was reminded of the discussion by an infographic a correspondent had sent to me. Its name — “Money: The Cold Hard Facts” — tells you what it is about, but what you don’t know until you see it is just how thoroughly the authors have researched the subject and how good of a job they’ve done representing the data visually. So I thought I’d offer a summary of what the three pieces tell us about the state of cash in 2013.

Is Fear Driving the Rise of Cash?

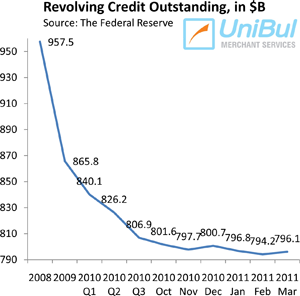

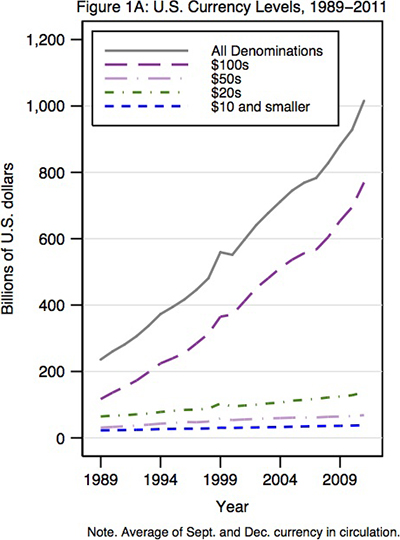

Below is an updated version of Goldfarb’s chart tracking the amount of U.S. currency in circulation, showing that, as of July 17, 2013, the total had reached an all-time high of $1.2 trillion, up by 45 percent from the $830 billion total of five years ago (July 16, 2008) — on the eve of the financial crisis that was about to plunge us into the deepest recession since the Great Depression.

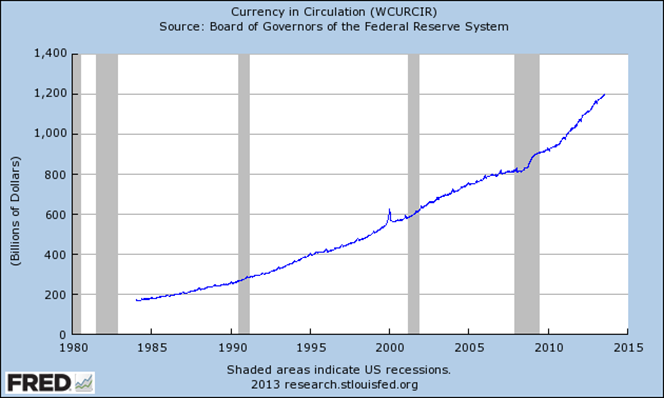

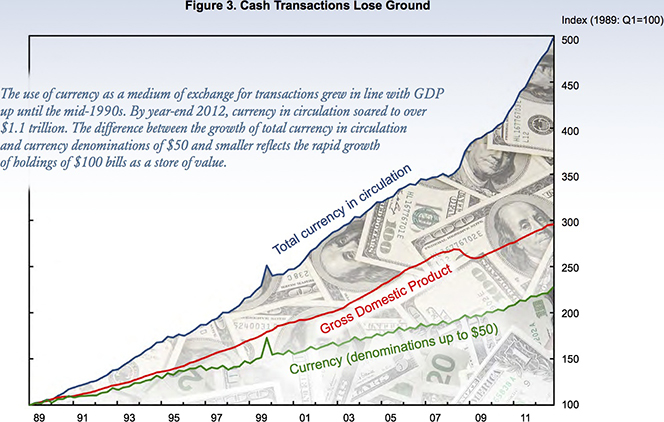

Goldfarb also gave us a fascinating chart comparing the growth of currency in circulation with the growth of GDP. Up until 1990, cash grew in line with GDP, but, as you can see, since then currency in circulation has been growing at an ever faster pace. However, not all cash is created equal: there is a huge difference between the growth of total currency in circulation and that of currency denominations of $50 and smaller (which, in fact, have been growing at a slower pace than GDP).

So all of the currency growth has come from the rapidly accelerating increase of the amount of $100 bills in circulation, as shown in more detail below.

Looking at all these graphs, Goldfarb concludes that people are just storing cash “in safety deposit boxes, under mattresses, in wallets”, rather than invest money in things or just keep it in the bank. But that explanation doesn’t convince me. If fear has been driving the rise of cash holdings since the Great Recession started, why was the growth of cash outpacing that of GDP in the booming 90s, too?

On Russian Beeznessmen and Safes

Krugman offers a different take, actually a couple of them. The first one has to do with circumventing the law:

The motives for holding cash, especially in the form of $100 bills, have been around for a long time; in large part it’s about evading taxes, and the law in general. (Latin American drug lords hoard high-denomination dollar currency; Russian beeznessmen do the same with big euro notes).

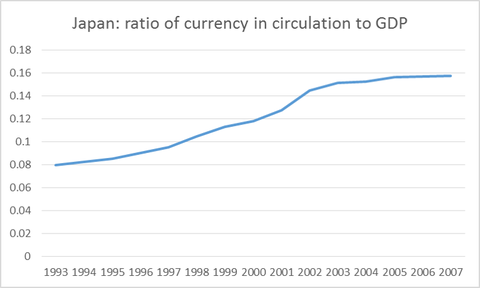

That is much more convincing than Goldfarb’s explanation, but Krugman doesn’t stop there. He notes that the near-zero interest rates, which we’ve had since 2008, have greatly reduced the opportunity cost of holding cash and proceeds to bolster his case by telling one of his favorite jokes — that back in the 1990s, when Japan was struggling with low growth and deflation, the only durable good selling well was safes. Sure enough, as Japan was grappling with its liquidity trap, the amount of its currency in circulation grew substantially in relation to GDP:

I think that would explain the quickening pace of currency growth in the U.S. since the financial crisis as well.

What Do We Know about Cash?

Now let’s turn our attention to the infographic I mentioned at the beginning. The author — MBA-in-Finance.org — has done a lot of work compiling all kinds of data to tell us, among other things that:

- The U.S. produces 26 million notes a day with a face value of around $907 million.

- “In God We Trust” did not appear on paper currency until 1963.

- The average life span of currency notes are as follows:

- $100 – 7.5 years.

- $50 – 4.5 years.

- $20 – 2 years.

- $10 – 18 months.

- $5 – 16 months.

- $1 – 21 months.

- Until 1804, no coin had their value on them. The size was the determination of the value.

- A penny costs 1.23 cents to make and the nickel 5.73 cents.

- The paper bills are made of a fabric containing 75 percent cotton and 25 percent linen and have red and blue synthetic fibers thrown in.

- Green ink is used because it was readily available when bills were first printed, it is resistant to chemical and physical changes, and the public associates it with strong and stable credit.

Without further ado, here is the infographic:

Image credit: Flickr / scriptingnews.