Financial Education Makes Prepaid Cards Cheaper for the Unbanked

The U.S. federal government runs some of the largest payment card programs in the world, with just the commercial segment doing about $30 billion in annual transaction volume in 2011. Most of the U.S. states are also running card programs, moving an additional $7 billion annually to electronic card payments in the process. The biggest reason for the transition to payment cards is that using them is much cheaper than using paper checks, which used to be the standard. On average, “the fully allocated cost of an electronic transaction is $19 versus $50 to $60 for a check payment”, Susan Herbst-Murphy from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia had calculated. Furthermore, card usage brought fraud and misuse to a historic low.

But there is another reason why payment cards — and prepaid cards in particular — are a better way for disbursing the government’s money: they benefit the recipients in a number of ways, including convenience, immediacy of fund availability and simplicity. Moreover, in theory at least, prepaid cards offer consumers a cheaper way to manage money than paper checks, which most recipients cash for a fee. However, the challenge has been that many recipients of governmental funds have not used their prepaid cards in the best possible way, incurring unnecessary fees along the way.

Well, it turns out that earlier this year the U.S. Department of Treasury, which runs the Direct Express prepaid card offering, had launched a financial capability program through PayPerks to help low- and middle-income consumers optimize their use of prepaid cards. Now a new paper from Herbst-Murphy analyzes the program’s early results.

Teaching the Unbanked

As already noted, there has been a shift toward providing reloadable prepaid cards to recipients of government benefits who do not have a checking or savings account capable of receiving electronic direct deposits — the unbanked. The early experience has “demonstrated that beneficiaries are 125 times more likely to have a problem with a paper check than with an electronic payment.”

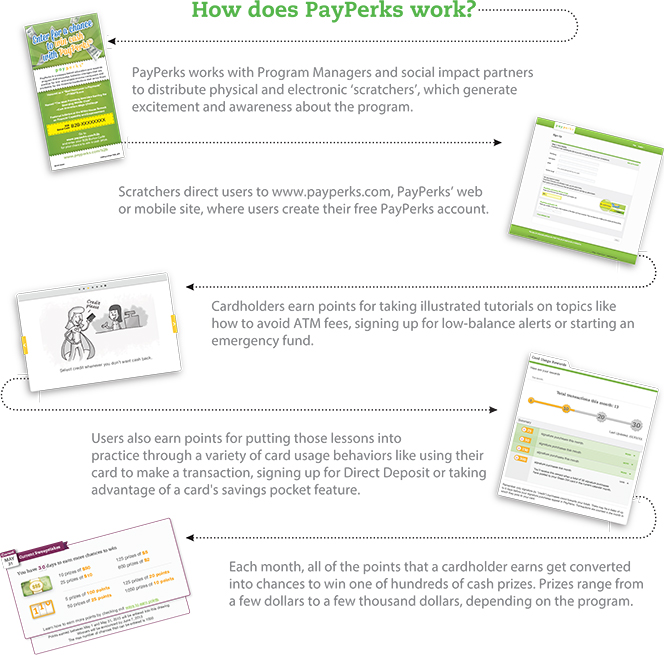

Not surprisingly, however, there have been issues when consumers who may never before have used a bank card were issued general-purpose prepaid cards. Some recipients were using their cards in ways that inflated the associated costs. To help modify such consumers’ behaviors, the government contacted PayPerks — a start-up whose platform merges online education with sweepstakes-type incentives to stimulate positive changes in consumers’ use of financial products. PayPerks’ initial focus has been on prepaid cards and educating cardholders on how to use them in ways that keep costs at a minimum. Here is how PayPerks’ program works:

After completing each module, participants are asked two questions. If a question is answered incorrectly, the member is given feedback explaining why the answer was wrong. A retest can be taken at any time.

People are awarded points for completing modules, for correctly answering questions about what they learned from the modules, and for demonstrating behavior that was learned in the modules. Points are awarded for having pay loaded onto the card, for using the card to make five purchases in one week (no matter how small since the goal is to encourage use, not overspending), for referring a friend to the PayPerks educational website, and for using the card at a gas pump (after completing the module explaining how to do that). Points can also be earned by participating in surveys designed to get demographic and attitudinal information (e.g., marital status, feelings about one’s finances) that allow for segmentation analysis.

Participants are then entered into sweepstakes, where points can be converted into cash.

Here is a visual representation of the PayPerks process:

People Are Interested

The first lesson from PayPerks’ pilot was that the target market had access to the internet –about 70 percent of the target population had regular access to the web. By accident, the researchers also discovered the importance of viral marketing. When a second round of invitations was sent out to a group of consumers, a number of those who initially passed on the program enrolled in it. It turned out that some consumers were dubious the first time around, but then heard good reports about the program from their early adopter co-workers. This positive feedback encouraged people to take action when given another chance to do so and PayPerks started repeatedly reaching out to them.

Close to a third of the pilot participants completed the surveys. They had no problem with sharing personal information, including gender and income. The researchers saw no obvious differences across age and geography — for example, forgetting passwords was consistent across all age groups.

The Takeaway

Unfortunately, Herbst-Murphy doesn’t go into details about the educational effects of PayPerks’ program on the participants, which, after all, is the most important criterion for assessing its effectiveness. Still, educating card users is the right approach and we cannot expect results to be achieved overnight. There is no question that prepaid cards are far superior to paper checks when it comes to making payments to the unbanked, as this and previous researches make clear. And, by the way, this is true for disbursing private, as well as public funds, even though some media would have us believe otherwise.

Image credit: YouTube / PayPerks.