Banks Abandon Debit Card Fees, Will Find More Subtle Ways to Raise Revenue

Bank of America was the last big bank to abandon its plans to charge a fee for debit card use. Yesterday’s announcement came on the heels of similar statements from JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, SunTrust and Regions. Citigroup and U.S. Bancorp had already decided against the idea.

So where does that leave us? Will the banks, humbled by popular outcry and intimidated by politicians’ threats, really give up on their plans to make up for the huge revenue losses they will suffer as a result of the passing of the Durbin Amendment? No, they won’t. What will happen instead is that the banks will find other, more subtle ways to get what they want.

Why Are Banks Doing It?

BofA and its peers knew perfectly well that any debit-related fees would be extremely unpopular. Charging a customer for carrying a debit card even sounds awkward. Here is what Richard Hunt, president of the Consumer Bankers Association, had to say on the subject, as quoted by the Washington Post:

We knew when we had to increase the fees that it would not be popular… We had millions of Americans never paying a fee in the first place. Americans are just not accustomed to paying for a checking account or debit cards. There’s a generation of Americans who have never done that.

Yet, they went ahead and did it anyway. Why? Here is Hunt again:

We would never have charged a penny for debit cards had Durbin not interfered… Maybe we should just go to Dick Durbin and ask him how to run a business. Since he’s got all the answers, since the government’s been so good about balancing their budget.

That about sums it up. Prior to the inclusion of Sen. Durbin’s eponymous amendment into the sweeping Dodd-Frank financial reform bill, banking was mostly free and there was not a hint of a debit-related fee. So how did the Durbin Amendment change the status quo?

Banks Are Looking for Ways to Fill a $7B Hole

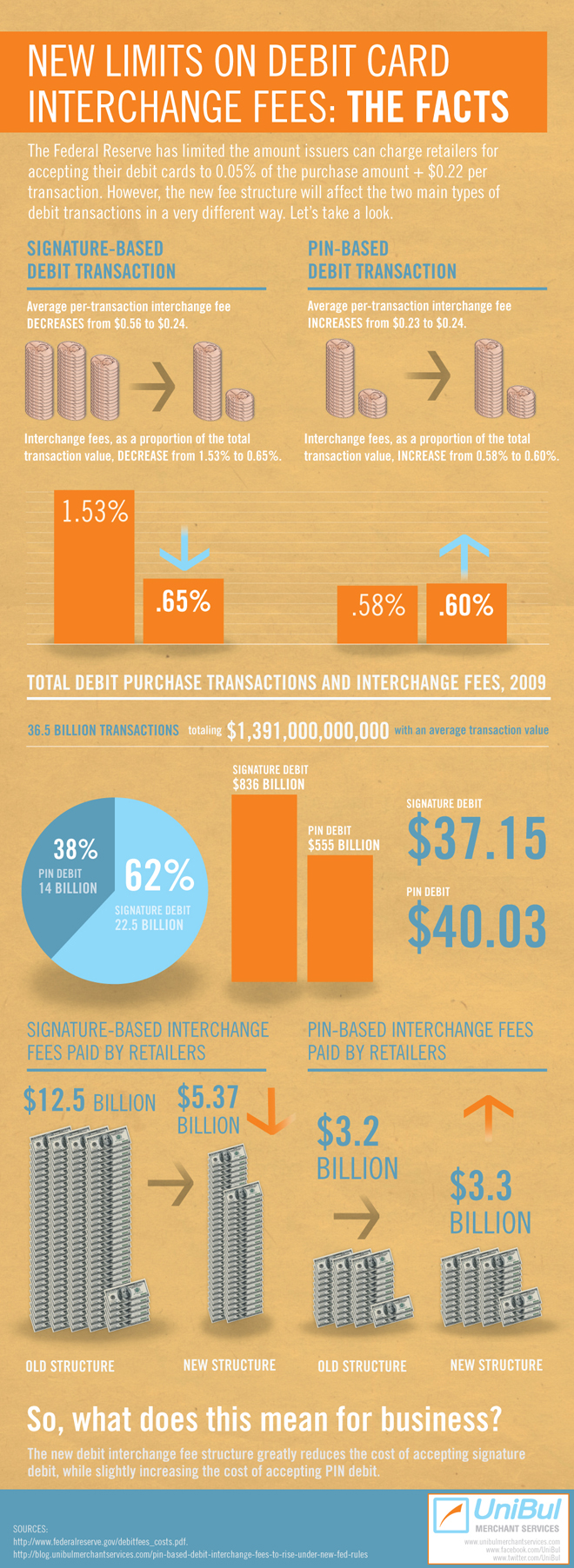

The Durbin Amendment charged the Federal Reserve with the task of ensuring that debit interchange fees, paid by merchants to card issuers for every debit card transaction, were “reasonable and proportional.”

The Fed initially proposed an interchange limit of $0.12 per transaction, but the banks were able to eventually get it lifted to a compound rate of $0.21 plus 0.05 percent and allowed issuers to charge additional $0.01 for fraud prevention measures.

All that translated into an average per-transaction interchange of $0.24, a 45 percent decrease from the pre-Durbin average of $0.44. As a result, banks stand to lose about $7 billion dollars in annual revenues. The infographic below illustrates the effects of the Fed’s rule on debit card issuers:

What Should Banks Do?

Sen. Durbin is, of course, well aware of the fact that his amendment is costing banks billions of dollars a year, but he doesn’t think that they should’ve had such high interchange revenues in the first place. Here is how he put it in a letter to Bank of America:

[Y]ou did not earn these fees by bettering your competitors in a free market, which is how Main Street businesses have to make their money. Rather, you earned these billions because the Visa and MasterCard duopoly fixed the same high swipe fee rates for your bank that they did for every other bank, thereby immunizing this revenue stream from competitive pressures that would hold fees at a reasonable level.

So the banks were making billions, because the system was rigged in their favor. Having made this point clear, Sen. Durbin made it plain what he thought of the banks’ efforts to make up for lost interchange revenues in a letter to Wells Fargo:

It is disingenuous for banks to claim they are somehow entitled to make up reductions to a revenue stream that they never would have received in the first place in a transparent and competitive market.

There it is. Sen. Durbin is telling Wells Fargo and its peers to just accept the huge losses and move on.

Well, the problem with this advice is that it cannot possibly be heeded. The banks Sen. Durbin is dictating to are businesses that exist to make money for their shareholders. If they can’t do that, their shareholders will go elsewhere. So the banks have no choice but to find ways to make up for the lost interchange revenues.

The Takeaway

The bottom line is that, one way or another, the banks will find ways to offset their losses. They will learn from the debit card fee debacle and devise more subtle tactics to achieve their objective. As Richard Hunt puts it:

Unfortunately, we have to look at all sources of revenue to recoup the fees… We’re trying to satisfy the customer and at the same time remain solvent. It’s a tricky situation.

New revenue sources will eventually be found and banks will recoup their losses. When the dust settles, what the Durbin Amendment will have achieved is an increase of revenue for retailers, due to lower card acceptance fees, at the expense of consumers who will be paying higher bank fees. The card issuers will not be worse off than before the changes took place.

Image credit: Avaloncreditcard.com.