Debit Card Fee Limit Lifted to 24 Cents, Consumers Will Still Pay for It

The Federal Reserve has issued the latest version of its final rule on the debit card interchange fee limit that retailers and issuers have been furiously fighting over for years. Fed’s decision has left both warring parties unhappy — the retailers will be paying higher fees than they thought they would and the issuers will be collecting fees that are twice lower than their current level.

For consumers, however, nothing changes. The Fed’s final rule makes it even less likely that retailers will pass any of their (now lower) savings on to consumers, which was probably not going to happen anyway, while issuers will still have to make up for their diminished debit transaction fee revenues by charging more elsewhere and they are already doing it.

Fed Lifts Debit Interchange Cap to 0.05% + $0.22

Wednesday’s rule places the limit on what issuers can charge for debit card transactions at 21 cents per transaction plus 0.05 percent of the transaction’s amount. Issuers can charge an additional cent per transaction for fraud prevention measures they have implemented.

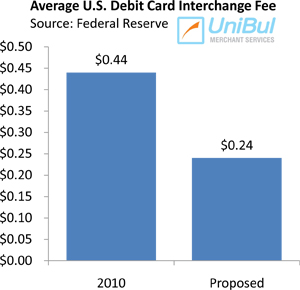

Once the new rule takes place in October (provided no more changes are made), the average debit transaction, which the Fed estimates to be $38, will generate for issuers an interchange fee in the amount of $0.21 + $0.01 + $38 x 0.05% = $0.239. At present, issuers collect 44 cents on average from a debit transaction, according to the Federal Reserve’s own calculations. So the new limit will translate into close to a 46 percent reduction in the amount issuers can collect in interchange fees.

Once the new rule takes place in October (provided no more changes are made), the average debit transaction, which the Fed estimates to be $38, will generate for issuers an interchange fee in the amount of $0.21 + $0.01 + $38 x 0.05% = $0.239. At present, issuers collect 44 cents on average from a debit transaction, according to the Federal Reserve’s own calculations. So the new limit will translate into close to a 46 percent reduction in the amount issuers can collect in interchange fees.

As with the previous version of the rule, issuers with assets of $10 billion or less will be exempt from the debit card interchange limit and will continue to charge whatever Visa and MasterCard decide is appropriate.

Who Will Benefit from the Fed’s Rule?

It is important to emphasize that the debit interchange fee reduction, whatever its final form, will not necessarily benefit all merchants. The only way your fees will go down automatically is if your pricing model is based on the interchange-plus pricing structure. Let me explain.

There are several different types of pricing models currently in use. With each of them the transaction fee merchants are charged is the sum of the interchange fee, collected by the issuer, an Association fee, collected by Visa and MasterCard and a fee charged by the payment processing bank.

The problem is that most pricing models simply bundle all these fees together and charge you a single fee, say $0.25 + 2.25% of the transaction amount. If this is your pricing model, what is going to happen is that, once the Fed rule is in place, the interchange reduction will automatically translate into an equal increase in the processor’s fee, so you will not see any difference. The beneficiary will be your processor.

In the case of the interchange-plus pricing structure, the three components of the transaction processing fee are kept separate and changes into any one of them have no effect on the others. So an interchange reduction will not be compensated by an increase elsewhere and the merchant will pocket the savings.

The Takeaway

The latest version of the Fed’s final debit interchange rule has not changed much. It is still good news for retailers and bad one for issuers. It is also still bad news for consumers who are already feeling the rule’s side effects, even before it has taken effect. Anticipating lower revenues, banks have begun creating new or expanding existing revenue sources. As a result, free checking accounts are going away, new bank fees are being introduced and old ones increased, interest rates are being hiked, rewards are being slashed, etc.

So the damage to consumers is already done and it will not be reversed, even if the Fed eventually decided not to change the interchange status quo after all. What we have here is a government-mandated redistribution of revenues from one industry to another, something it has no business doing.

Image credit: Kasasa.com.

I keep getting the impression that the government is trying to cause our economy to crash, the the houseing incentives to banks that put us into the economic state we are in now and this which I understand the reason for it but was not thought out enough before putting in place. While my bank for now is not charging to have a debit card it seems to be unavoidable that it was eventually happen. The real question is who put Senator Dick Durbin in this position when he didn’t seem to have an ideal this would happen and yes I have read his reason in the NY-Times but to use the excuse to goto a smaller bank does not help if all the Bank of America customers moved, excuding the people with mortgages with them, then the new bank will be in the same position as Bank of America was.

I am skeptic of the need to replace this lost revenue on the issuer side. This only affects large banks with assets over $10B? Well lately the bigger banks have been consolidating, and either buying smaller banks or pushing them out of business. So we now have a handful of extremely large banks basically running the whole system, with nothing but their ex- and future-employees in all the key positions in Washington, raking in literally hundreds of billions every year in profits despite the depression the rest of the country is mired in.

So my question is, when you’re already gouging the populace at this level, what difference does a few hundred million make? Keep in mind that banks originally made their money by aggregating their customers’ deposits and using it to invest or make loans with interest. Which they still do. Now, due to Republican-demanded deregulation, they are able to make gigantic profits on just about anything they can dream up and swindle us with.

I told U.S. Bank yesterday that if they even consider charging me a single cent for my checking account or debit card, I will simply take my business to another bank that is happy with the enormous pile of cash they already make on my money sitting in their hands.

Whether or not the banks have a “right” to make up for lost revenues is a mute point. The reality is that they will try and keep trying until they eventually succeed in finding the least conspicuous ways to do it. When it’s all said and done, banks will not be worse off, merchants (especially large ones) will have tapped into a whole new revenue stream and consumers will be footing the bill.