Prepaid Cards: the Bank Accounts of the Unbanked

Sanjay Poonen, a senior executive at software giant SAP, argues in today’s Financial Times that “emerging markets have created a successful model for the unbanked that developed economies could follow”. To make his case, Poonen enlists the help of a number of companies in developing countries, which have found innovative ways to serve the financial needs of people with no access to traditional bank services and argues that companies in the U.S. and other high-income countries should follow their lead. “Since mobile financial services in emerging markets are successful”, Poonen asks, “why not apply the same models in established markets and provide clear pathway into more formal banking?”

Well, as I’ve argued on this blog before, alternative financial models that work well in developing markets are simply not well-suited to serve consumers in high-income countries. For example, the type of mobile money transfer service provided by M-Pesa in Kenya and elsewhere could never be successfully implemented in the U.S. simply because there are so many alternatives here, at least some of which are either cheaper or more convenient, or both. However, somewhat contradictory to his argument, having told us to look for the emerging markets for guidance, Poonen nevertheless points to a product that has been in use in the U.S. for decades, which he identifies as a perfect fit for the unbanked — prepaid cards. He is right, of course — prepaid cards were indeed designed with the unbanked in mind. Moreover, the best prepaid cards today are better than most checking accounts. Unsurprisingly, prepaid use in the U.S. has been soaring.

Unbanked in the U.S.

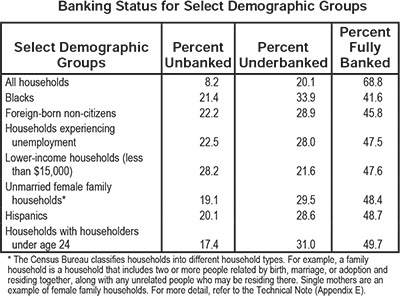

To give us a sense of the size of the unbanked segment of the population, Poonen cites data from an FDIC report issued in September of last year (although, perplexingly, the author does not identify his source). According to that survey, more than a quarter of American households (28.3 percent) are either unbanked or underbanked, which means that they rely on alternative financial services, such as prepaid cards and payday loans, for some or all of their financial transactions. The FDIC found that most likely to fall into one of these categories are groups that include non-Asian minorities, foreign-born non-citizens, unmarried families, less educated households, younger households, unemployed households, non-homeowners, and lower-income households.

Here are the survey’s key findings:

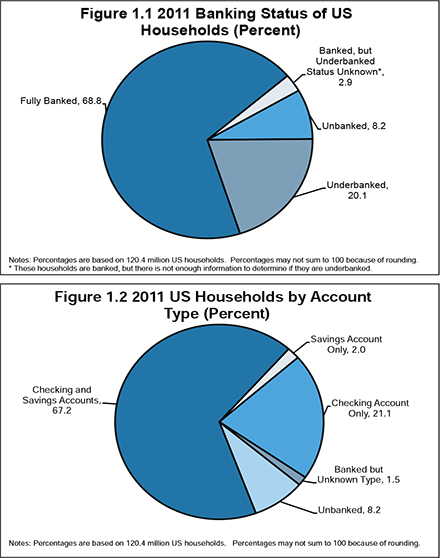

- 8.2 percent of U.S. households are unbanked — 10 million households, in which live approximately 17 million adults who lack any kind of deposit accounts.

- 20.1 percent of U.S. households are underbanked — 24 million households, in which live 51 million adults, do have a bank account, but also rely on alternative financial service providers.

- 29.3 percent of households do not have a savings account.

- 10 percent of households do not have a checking account.

- 67.2 percent of households have both checking and savings accounts.

So consumers relying on non-traditional services for at least a part of their financial transactions make up a sizable chunk of the U.S. population. But what are their options?

Serving the Unbanked

Poonen praises the successes of developing-world financial service stars like M-Pesa and Bangladesh-based Dutch Bangla-Bank Limited (DBBL) and urges that the same models are applied in developed markets. He then points to the increasing popularity in the U.S. of prepaid cards and finds what he is looking for. Prepaid cards, the author informs us, are not only offered by “[p]ioneering banks”, but are “using a business model similar to the one that has worked in emerging markets: a simple account accepted by a wide range of merchants.” Now, I am really struggling to make a meaningful parallel between the M-Pesa model and the prepaid-card one, but some new-age prepaid cards are nevertheless an ideal fit for the needs of the unbanked.

Curiously, the most prominent of the “pioneering banks” in question in the U.S. are Chase and American Express, which over the course of the past couple of years or so launched several incredibly good prepaid cards: Chase Liquid, the American Express Prepaid Card and Bluebird. We reviewed Bluebird when it was launched in October of last year and here is the gist:

Not only does Bluebird come with no monthly fee and is virtually free of other charges, but it offers something no other prepaid card does: cardholders can deposit checks into their prepaid accounts via the Bluebird mobile app. Furthermore, as Bluebird is built on the American Express?áServe?áplatform, it incorporates a host of capabilities that are not to be found in other prepaid cards. So, unless you still write paper checks to pay your bills, you should seriously consider replacing — or supplementing — your existing checking account with Bluebird.

Much the same can be said about Liquid, whose only disadvantage when compared to Bluebird is that it comes with a monthly fee of $4.95. A year ago American Express went as far as to launch a program, called Make Your Move, to allow prepaid users with good track records to eventually upgrade to a charge card, irrespective of the cardholder’s overall credit history.

The Takeaway

So, yes, the new-age prepaid cards are better than most checking accounts and there is no surprise that their popularity is rising as fast as it is — prepaid card usage in the U.S. is growing faster than the use of credit and debit cards. And I expect that this trend will continue in the years ahead, as more and more unbanked Americans discover that prepaid cards offer a great way for them to enter the mainstream financial system.

Image credit: Mybanktracker.com.