Regulating Prepaid Cards, Again

Over the course of the past few months, regular readers of this blog have been subjected to an interminable string of articles aimed at pinning down the essence of prepaid cards and identifying the differences among the three major payment card types (the other two being credit and debit). If you thought that there was no need for such an exercise, you should read yesterday’s headlines in the nation’s two leading newspapers about the latest efforts to regulate prepaid. The Wall Street Journal’s was “New Rules for Prepaid Credit Card Companies” and the New York Times’ was “New Rules for Prepaid Debit Cards.” Of course, because you read UniBul’s blog every day, you know perfectly well that prepaid cards are neither debit nor credit cards, but a unique payment product (a modest dose of self-satisfaction is certainly allowed).

But today I’d like to talk about the new regulatory efforts in question. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has begun a process of creating new rules that would apply to a subset of the prepaid card category known as “general purpose reloadable” (GPR) cards. What you should know is that in August 2010, the Federal Reserve, acting under a mandate given by the CARD Act of 2009, enacted a set of rules that applied to the other major prepaid sub-category — gift cards — but left the GPR cards unaffected. Now the CFPB is considering whether all or “only certain” aspects of these rules should be applied to GPR cards as well. I suspect that, when it’s all said and done, the GPR cards will get the same, or at least very similar, treatment. With that in mind, let’s take a look at what the Fed did for gift cards a couple of years ago.

How Gift Cards Were Regulated

Before I begin, let me remind you that gift cards are non-reloadable prepaid cards that can be used at a particular store or group of stores or, if they display a Visa, MasterCard, American Express or Discover brand logo, they can be used anywhere this brand is accepted.

Here are the Federal Reserve rules that have applied to all gift cards since August 2010:

- Limits on expiration dates. The money on your gift card will be good for at least five years from the date the card is purchased. Any money that might be added to the card at a later date must also be good for at least five years.

- Replacement cards. If your gift card has an expiration date you still may be able to use unspent money that is left on the card after the card expires. For example, the card may expire in five years but the money may not expire for seven. If your card expires and there is unspent money, you can request a replacement card at no charge. Check your card to see if expiration dates apply.

- Fees disclosed. All fees must be clearly disclosed on the gift card or its packaging.

- Limits on fees.Gift card fees typically are subtracted from the money on the card. Under the new rules, many gift card fees are limited. Generally, fees can be charged if

- you haven’t used your card for at least one year, and

- you are only charged one fee per month.

These restrictions apply to fees such as:

- dormancy or inactivity fees for not using your card,

- fees for using your card (sometimes called usage fees),

- fees for adding money to your card, and

- maintenance fees.

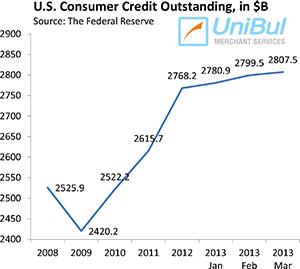

Crucially, branded non-gift prepaid cards that are “intended to be used like a checking account substitute” — like the American Express one or Chase Liquid — were not covered by these rules and this is the shortcoming the CFPB is addressing with the proposed rules. The watchdog’s attention was attracted by the very fast growth of prepaid in general and the GPR segment in particular. In its notice the agency cites a report, according to which the number of active GPR cards issued by the two largest U.S. issuers have more than doubled, from about 3.4 million in the first quarter of 2009 to over 7 million in the first quarter of 2012. Moreover, as CFPB chief Richard Cordray told the NYT, GPR users are “in many instances, the most vulnerable among us.”

The Takeaway

There can be no question what the outcome of this initiative will be. The CFPB tells us on its website that it “intends to extend federal consumer protections to prepaid cards” and will do just that. This is the right thing to do and I support it. I only hope that the agency doesn’t overreach and make it more difficult and / or expensive for issuers to run prepaid programs. Over the past year many mainstream issuers have entered a market that used to be dominated by largely unknown companies and as a result prepaid cards have become vastly better. The CFPB should do its best to keep the evolution going in the same direction.

Image credit: MyBankTracker.com.

Why not just issue debit cards with checking accounts, rather than deal with prepaid? It’s pretty much the same thing and there is no way for cardholders to get in debt. What’s more, the checking accounts are regulated, covered by FDIC insurance and some of they pay interest. It would be checaper than having to go through a whole new regulatory process.

Some of the people who use prepaid cards cannot open checking accounts because of past issues. So prepaid is not an option, it’s a necessity and need to be properly regulated just as other cards are. They should be also FDIC insured too.

There is no amount of regulation that will protect people from their own stupidity. Prepaid cards are very well protected as they are. This is just a waste of government money.

This has nothing to do with people’s stupidity. No amount of intellect will protect you from losing all of the money you have in your prepaid card if you lose it and the issuer refuses to issue a replacement card with the remaining balance. These are the kinds of things we are talking about and they are needed.

If the banks were playing by the rules and were not trying to scam us as all of them do, then there wouldn’t be any need for regulation. As it is, however, and given the lessons from the recent past, we can’t trust them but have to monitor them very closely.

People need to look at the disclosure on the card’s package when they buy it. It’s all there: activation fees, monthly fees, ATM fees, inactivity fees, etc. Actually, if you just go online, you can find all these fees there, compare cards and choose the best one for you.

Card issuers are not required to disclose all terms and conditions of their prepaid programs and that is what the CFPB wants to make them do, as they should. Why is that a problem?

If you buy from verified sellers, like Suze Orman’s webiste for example, everything is fully disclosed and in much more details than you would find on many credit card websites. Information is not the issue, it’s all out there for everyone who wants to see it. The question is whether people bother to read the terms and regulation can’t help you if you don’t.

Suze Orman’s card is actually a case in point for why prepaid needs to be regulated. She keeps saying that her card helps people build their credit score, which is simply not true. This is one of the things the CFPB is trying to do – to ensure that issuers are not misleading consumers.

Prepaid cards are used primarily by the unbanked, including immigrants and college students. These are people who can’t get a debit card for whatever reason but they deserve to have access to a card that doesn’t rob them of their cash. So this is a step in the right direction.

Prepaid cards have been steadily improving and many of them now are practically fee-free and some of them are better than most debit cards. So why does the government need to interfere right now? More likely than not, they will do something stupid and force the issuers to charge new fees.

This is another proof that the CFPB should not exist at all. They are just looking for things to regulate, even if there is no need for it. Prepaid cards are fine as they are, no need to fix something that isn’t broken. But that’s not how Cordray sees it.