Prepaid Cards Are Getting Better, Much Better

That is the main takeaway from the latest report on the subject released by the Pew Charitable Trusts. Actually, this is the second part of Pew’s prepaid card report, the first of which — covering consumers’ attitudes toward the product — we reviewed last week. The first installment told us that, far from being a niche market serving America’s unbanked population, prepaid cards are being the payment product of choice for an already large and increasing number of consumers with access to bank accounts and credit and debit cards. The primary reason for prepaid’s growing popularity, the researchers found, was that for most users, “prepaid cards are a mechanism to avoid the temptations and problems of the past”.

Well, the report’s second part strongly suggests that many of those prepaid users who have access to other payment products, but have nevertheless chosen prepaid, have made the right choice. The costs of using prepaid cards can be lower than the costs of using checking accounts and the debit cards attached to them and, unlike credit card users, prepaid users cannot incur any interest charges. Furthermore, most prepaid issuers, and particularly the large banks which have entered the market over the past couple of years, protect their prepaid users with FDIC insurance, even though they are not required to do so. Of course, the researchers warn of some still-existing risks of using prepaid, but the inescapable conclusion is that the product has improved immensely. Let’s take a look at the report.

The Prepaid Market Is Changing

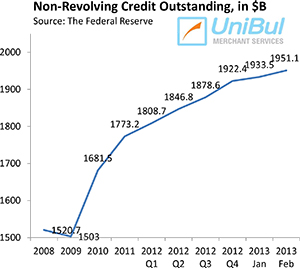

U.S. consumers have loaded $64.5 billion onto general purpose reloadable (GPR) prepaid cards in 2012, the researchers remind us, up from $56.8 billion in 2011. Pew defines a GPR prepaid card as a product that allows consumers to load funds via cash and direct deposit, and provides the ability to spend money at “unaffiliated merchants”, as opposed to a particular merchant, and to access funds through ATMs. These cards bear the logo of a payment network, such as Visa or MasterCard, and can be used anywhere that network’s cards are accepted.

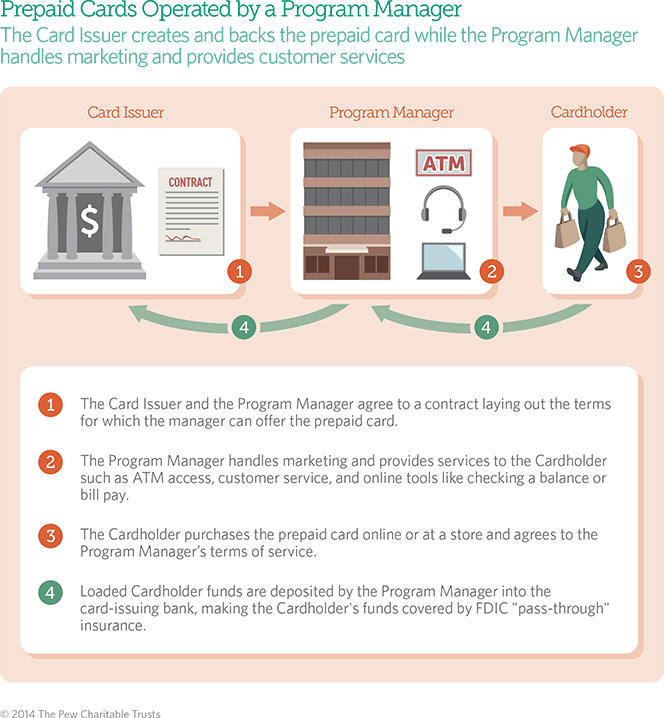

The huge growth in GPR volumes is still dominated by a few non-bank companies, such as Green Dot Corp. and NetSpend Corp. In fact, the five biggest such non-bank companies (“program managers”, as the researchers call them), have accounted for about 76 percent of the total volume loaded on GPR prepaid cards in 2012. However, the second half of the top 10 GPR prepaid cards by load volume now includes three large banking institutions — JPMorgan Chase, Regions Financial Corp. and BB&T — none of which was there in 2011.

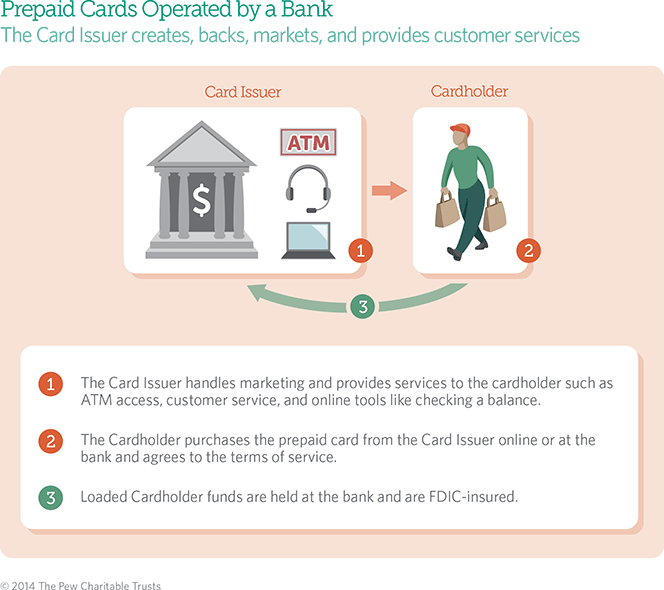

As the report notes, given their size and bank name recognition, if the big banks chose to aggressively invest in and promote their prepaid programs (which seems to be their intention), they could quickly capture a much larger share of the market. Furthermore, a bank-powered prepaid program is a much more straightforward affair than a non-bank one, as it eliminates the “program manager” layer, which is not at all necessary and it only adds to the program, and the end users’, costs. Here is a visual representation of the two programs, which makes the difference quite clear. First, the non-bank type:

And here is the direct type of prepaid program:

Prepaid Cards Are Getting Cheaper and Better

Prepaid’s traditional fee structure is changing and is now more closely resembling traditional checking accounts, the report finds. More prepaid cards are now charging monthly fees but not charging transaction-based fees, such as point-of-sale or customer service fees. More importantly, Pew finds that in 2013 prepaid cards were slightly cheaper than they were in 2012.

The researchers have created three model consumers — savvy, basic and inexperienced — to measure the cost of prepaid cards based on three distinct behavior patterns, as described in the table below:

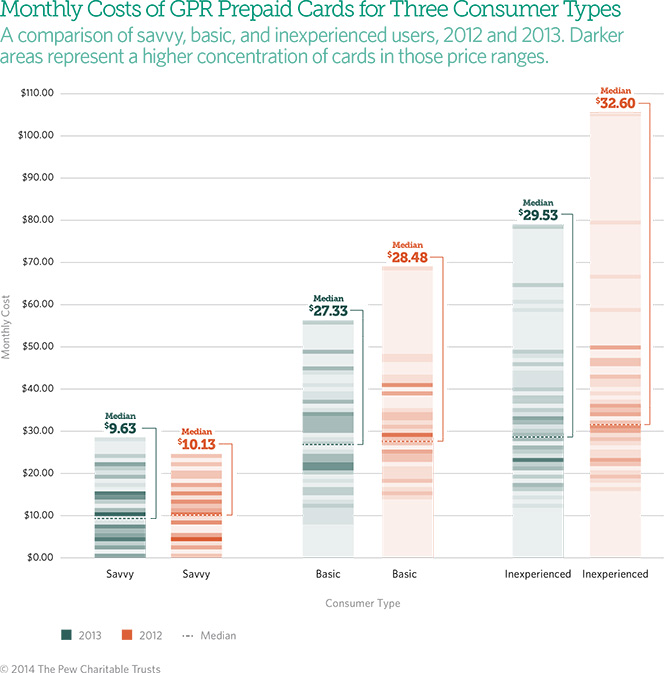

The researchers find that the cost of using GPR prepaid cards has decreased slightly in 2013 from 2012. The median cost for the savvy and basic consumer has each declined by less than $2 and the median cost for the inexperienced consumer has gone down by more than $3. The minimum and maximum fees have not changed greatly.

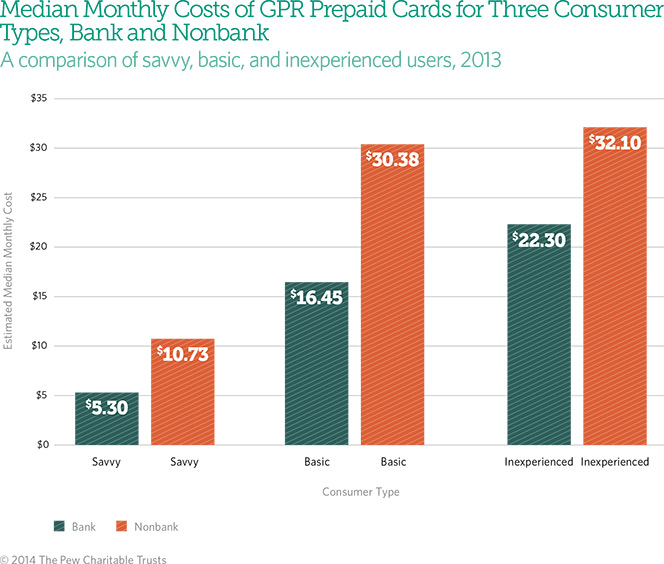

Furthermore, for each of the three models, the 10 card programs managed by banks are significantly cheaper when looking at the medians. For the savvy consumer, bank GPR prepaid cards have a median cost of $5.30, compared with $10.73 for non-bank cards. For the basic consumer, the two medians are $16.45 and $30.38, respectively. And for the inexperienced consumer, the two medians are $22.30 and $32.10, respectively.

Bank-managed prepaid cards are much less likely to charge for transactions other than out-of-network ATM withdrawals, which make them appealing to all consumer types. Furthermore, the savvy consumer is not paying many fees. In fact, for most cards, the only fee incurred by savvy consumers is the monthly fee, which tends to be lower for bank-managed than non-bank-managed programs. For the basic and inexperienced consumers, the availability of a bank network of physical locations where they can use their bank-managed cards at low costs or none at all means the cards are much less expensive.

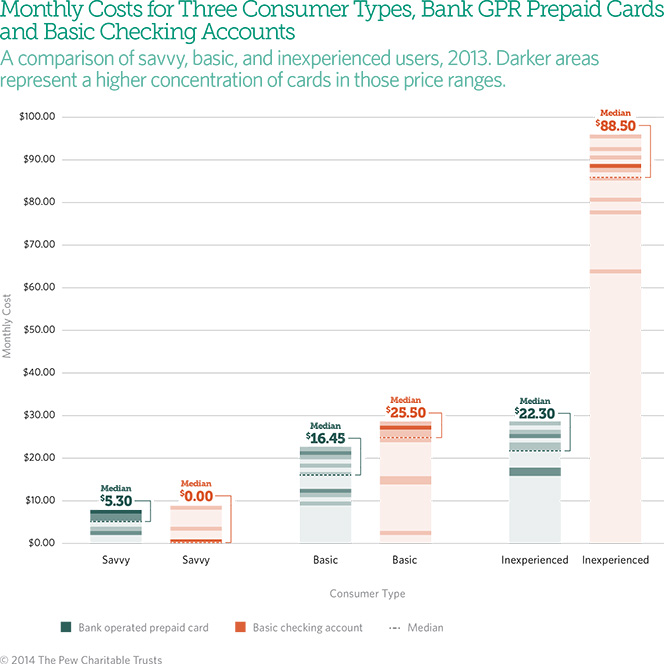

Considering all these findings, you may not be surprised to learn that, for many consumers, the researchers find the GPR prepaid card to be a better deal for reducing costs than the most basic checking account offered by a large financial institution. The biggest saving offered by these bank GPR cards is avoiding overdraft and penalty fees that cover lack of funds.

Other key findings are:

- GPR prepaid cards generally do not offer consumers the limited liability protection required by federal law for checking accounts.

- Almost all GPR prepaid cards explicitly state that cardholders’ funds are covered by Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) insurance, with the disclosure being much clearer in 2013 than it was in 2012.

- Arbitration agreements that require cardholders to settle any dispute using a private, third-party, decision maker are increasingly part of GPR prepaid cardholder terms.

Now, the researchers are continually referring to overdraft fees as a possible unwelcome addition to the otherwise very good and improving new prepaid card entrants. However, as they themselves seem to realize, that is unlikely to take place. As the report notes, the biggest reason large banks have entered the prepaid market in the first place is that the Durbin Amendment made debit cards a much less profitable line of business for them. Prepaid cards are not covered by the amendment, but only under certain circumstances, the most relevant of which prohibits charging “a fee for an overdraft, including a shortage of funds or a transaction processed for an amount exceeding the account balance”. So I just don’t see any possibility that a large issuer would introduce an overdraft feature to its prepaid offering.

However, the Durbin Amendment still manages to cause damage even in this payment card sector by prohibiting large banks from offering online bill payment features with their prepaid cards, that is if they want to keep the exemption from the Durbin Amendment, which of course they do. Yet, as we have previously noted, this requirement does not apply to American Express, which gives the company’s great Bluebird prepaid card offering a huge competitive advantage. Note that AmEx, whose overall payment card operations are bigger than, say, Chase’s, can and does offer bill payments on its prepaid cards, even as Chase is prevented from doing so, because of its size! The difference that matters here, however, is that American Express doesn’t issue debit cards, while Chase does.

The Takeaway

So prepaid cards issued by large banks are clearly better than the more traditional alternatives and, as we have seen, there are good reasons for that. The Pew researchers have made suggestions on how to make prepaid cards even better and some of these make good sense, but most of them, such as FDIC insurance and proper disclosure of the terms of service, have already been implemented by the big issuers, as we’ve just seen. Moreover, and as already noted, Pew’s overdraft obsession is really unwarranted. So, yes, prepaid cards have come of age and are now a genuinely good alternative to checking accounts.

Image credit: Pewstates.org.