Overdraft by the Numbers

The U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has just released a report on the issue of overdraft fees. You may recall that in February of last year the consumer watchdog launched an inquiry into bank overdraft practices and proposed a “penalty fee box” — a disclosure on consumers’ checking account statements that would “highlight” the overdrawn amount for the month and the related penalty fees. As I said back then, that penalty box was not needed at all — all penalty fees were already listed on all checking account statements even under existing rules, but “highlighting” seemed to be the only thing the CFPB could have thought of. And anyway, did the CFPB guys think that people didn’t know how much they paid in overdraft fees, so the amount should be highlighted for them?

The highlighting thing went nowhere and this year the bureau seems to have changed course. Richard Cordray, the CFPB’s director, tells us in a statement that, even though “overdraft protection can, in some instances, create greater risk of consumer harm”, banks should nonetheless not be “precluded from offering overdraft coverage”. Of course, he promised to keep looking into the issue. The report is valuable in that it gives us a lot of interesting data to look at and I thought I’d share it with you.

U.S. Consumers Charged $32B in Overdraft Fees in 2012

An overdraft program can be triggered when a consumer attempts to spend or withdraw funds from their checking account in an amount that exceeds the account’s available funds. At this point, the bank can choose to process or reject the transaction and if it decides to process the payment, the consumer may be charged an overdraft fee. Now, it should be noted that, for overdraft purposes, there is a difference between transactions initiated by check or ACH and debit card transactions. Whereas the CARD Act of 2009 required that consumers explicitly opt-in for overdraft protection, before they can be enrolled into it, the requirement covers only debit card transactions, but it does not apply to check and ACH payments. So, to give you an example, your bank wouldn’t need your permission to process an ACH payment on an e-commerce website when you didn’t have enough money in your checking account to cover it, but would need one if you chose to use your debit card, even though both payments were funded from the same bank account. Of course, in the former instance you would still be charged an overdraft fee, typically called a non-sufficient funds (NSF) fee (an NSF fee would not be charged if the bank rejected the transaction).

An overdraft program can be triggered when a consumer attempts to spend or withdraw funds from their checking account in an amount that exceeds the account’s available funds. At this point, the bank can choose to process or reject the transaction and if it decides to process the payment, the consumer may be charged an overdraft fee. Now, it should be noted that, for overdraft purposes, there is a difference between transactions initiated by check or ACH and debit card transactions. Whereas the CARD Act of 2009 required that consumers explicitly opt-in for overdraft protection, before they can be enrolled into it, the requirement covers only debit card transactions, but it does not apply to check and ACH payments. So, to give you an example, your bank wouldn’t need your permission to process an ACH payment on an e-commerce website when you didn’t have enough money in your checking account to cover it, but would need one if you chose to use your debit card, even though both payments were funded from the same bank account. Of course, in the former instance you would still be charged an overdraft fee, typically called a non-sufficient funds (NSF) fee (an NSF fee would not be charged if the bank rejected the transaction).

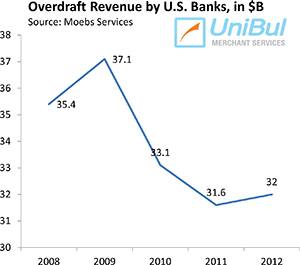

It turns out that overdraft fees are a huge source of revenue for U.S. banks. According to research firm Moebs Services, in 2012 U.S. banks collected $32 billion dollars in revenue from overdraft fees, a 1.3 percent increase over the 2011 total, but still 13.7 percent below the peak of $37.1 billion reached in 2009.

Overdraft by the Numbers

The CFPB’s report finds, unsurprisingly, that overdraft programs can be costly for consumers who use them, but there is much more to it than that. Here are the reports main findings:

1. Overdraft is costly:

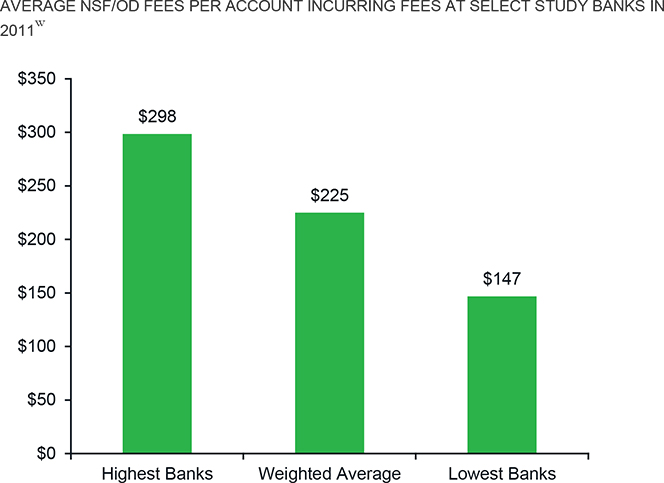

Costly service: The banks in the study used different methodologies for measuring the incidence of accounts that incurred overdraft and non-sufficient funds (NSF) fees. The percentage of accounts experiencing at least one overdraft or NSF transaction in 2011 was 27% for study banks that tracked all incidences for all accounts opened at any time during 2011 and 20% for study banks utilizing other methods. The average overdraft- and NSF-related fees paid by all study bank accounts that had one or more overdraft transactions in 2011 was $225 and varied by as much as $201 between study banks.

The chart below shows the range of NSF or overdraft (OD) fees charged to accounts with at least one NSF / OD transaction that were open at any point in 2011.

Now, if the calculation is done for accounts that were active as of the end of the year, as opposed to being active at any point during the year, the average NSF / OD fee for the surveyed banks becomes $301 and it ranges from under $250 to over $350.

2. Heavy users:

Heavy overdrafters: A small percentage of consumer checking accounts incur a substantial number of overdrafts. The proportion of consumer checking accounts with at least one overdraft or NSF that were heavy overdrafters (defined for purposes of this paper as consumers incurring more than 10 non-sufficient funds or overdraft transactions during 2011) was 27.8% for study banks that tracked all incidences for all accounts opened at any time during 2011 and 13.5% for other study banks.

3. Opting in:

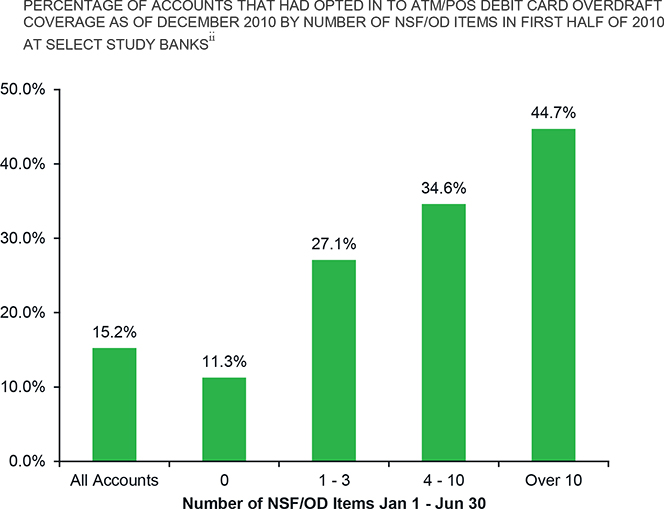

Overdrafters who did and did not opt in: Consumers’ overdraft experiences before and after the implementation of the opt-in requirement provide some insight into the impact of the new opt-in requirement. While a majority of accounts that were the heaviest overdrafters (with more than 10 overdraft or NSF transactions in the first half of 2010) did not opt in, these accountholders opted in at a higher rate than accounts overall (44.7% compared to 15.2% of all accountholders among the sample of banks). While both heavy overdrafters who did and did not opt in experienced a reduction in fees per account in the second half of 2010, the reduction in fees for those who did not opt in was $347 greater, on average, than for those who did opt in.

The average opt-in rate in the CFPB’a sample is 16.1 percent, but it ranged widely among the studied banks. The highest opt-in rate was associated with accounts with heavy overdraft history. As shown in the chart below, 44.7 percent of accounts with more than 10 NSF / OD items during the first six months of 2010 chose to opt into the program by the year’s end:

4. Account closures:

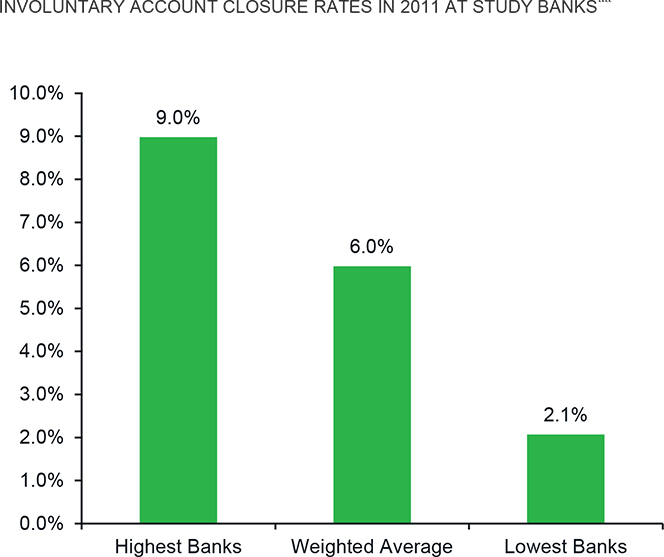

Involuntary account closures: Some banks close consumer checking accounts at significant rates, mostly due to unpaid negative balances. Study banks involuntarily closed 6.0% of consumer checking accounts that were open or opened during 2011. Involuntary closure rates varied widely; the study bank with the highest involuntary rate closed 14 times more of its accounts in 2011 than the bank with the lowest involuntary closure rate. While not all negative balances are caused by overdraft, the majority of negative balance incidents result when consumers overdraw their accounts.

Here is the chart:

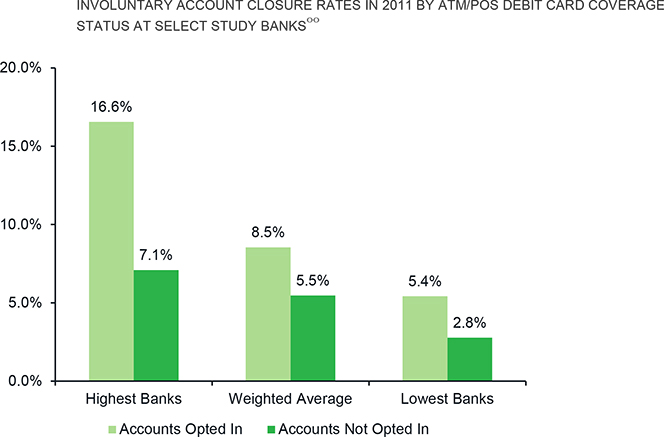

At each of the surveyed banks, opted-in accounts had higher rates of involuntary closure — 8.5 percent — than accounts that had not opted in — 5.5 percent. Here is the chart:

The Takeaway

It is clear that overdraft is an issue for a relatively small group of consumers who incur a disproportionately high number of overdrafts. Yet, these are also the consumers who are most likely to opt into the service — meaning that they are most likely to give their bank permission to process payments for which there are not enough funds in their bank account, even though they know that overdrawing their account is costly (up to $35 per instance). So what’s the issue then?

Image credit: afagen.