It Is a Phone and a Bank

“Is it a phone, is it a bank?”, asks The Economists in its report on the latest financial service to be offered by Kenya’s Safaricom — the telecommunications company behind M-Pesa — the hugely successful mobile transfer service. M-Shwari — as the new service is called — is a full-fledged bank account, which offers access to micro loans and it is all managed from the account holder’s mobile phone.

It seems to me that M-Shwari can justifiably lay claim to being the first true mobile banking service. All other products to which the term has been applied, in developed countries or elsewhere, have actually referred to mere additions to more traditional financial products. In fact, I’ve always had an issue with the prevailing definition of mobile banking. For example, the act of accessing your account through a phone to check your available balance is considered banking, whereas I think that it should be classified as information gathering. Similarly, receiving a text alert from your bank reminding you that you had scheduled a utility payment for tomorrow is not mobile banking; it is an e-calendar feature. The way I see it, banking — mobile or otherwise — has to do with managing money and moving it from one place to another. And that is precisely what M-Shwari does. Let’s take a look at the service.

What Is M-Shwari?

M-Shwari is a financial service offered by Safaricom to its 19 million Kenyan subscribers, almost 15 million of whom, The Economist reminds us, are already M-Pesa users. Safaricom describes M-Shwari as “a paperless banking service offered through M-Pesa” that enables users to:

- Open and operate an M-Shwari bank account through their mobile phones, without the need to visit any bank to fill out bank account opening forms.

- Move money in and out of their M-Shwari savings accounts to their M-Pesa accounts at no charge.

- Earn interest on their savings balance. The savings interest rate depends on the deposited amount and varies from 2 percent for amounts of up to 10,000 Kenyan shillings (KSh) ($116.8) to 5 percent for amounts of more than 50,000 KSh ($584.1).

- Get a micro credit and receive the loan instantly in their M-Pesa accounts. The minimum loan amount is 100 KSh ($1.2) and “the maximum amount is dependent on your loan amount limit”, Safaricom tells us. There is no interest on the loan, but there is a one-time “loan facilitation fee” of 7.5 percent of the borrowed amount. However, considering that loans are payable within 30 days, the set-up fee is not at all a trivial one.

All this is done through the user’s mobile phone. There are no minimum balance requirements and the regular M-Pesa transaction fees apply. The banking component of the service is managed by the Commercial Bank of Africa.

Off to a Fast Start

M-Shwari’s marketing “leans heavily on a rags-to-middle-class dream”, The Economist tells us, giving us the following example:

A television advertisement shows one of Kenya’s many penniless backstreet car mechanics toiling away under an old banger. He uses the service to save for a $60 box of tools and ends up with a garage equipped with computers and staff in overalls.

The same uplifting message is conveyed through M-Shwari’s official video:

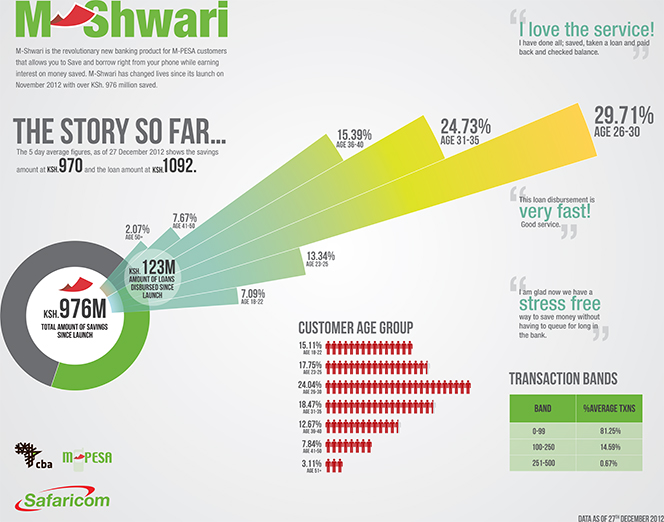

Evidently, the message is resonating with Kenyans, 2.3m of whom have subscribed to M-Shwari in the service’s first four months and 900,000 of them have active accounts, according to The Economist. The newspaper tells us that total deposits to date amount to 4 billion KSh ($46.7 million) and one-third of the users have applied for small loans, averaging around $12 each. So total deposits have more than quadrupled from the end of last year when they stood at 970 million KSh ($11.3 million), according to data released by Safaricom and presented in the infographic below, while the average loan amount has slightly decreased from the $12.8 figure calculated back then.

As you can see in the infographic, the vast majority of M-Shwari borrowers are young Kenyans — about half of them are 30 or younger and about three-quarters are 35 or younger.

The Takeaway

The Economist cautions us that the vast majority of consumers living in “average Kenyan towns and villages” have still not embraced the service. The author cites a report, which has found that the median transaction amount in the studied group was just $1 and most of it was in paper money, adding that the “handful of mobile payments that showed up averaged $75.” Well, that may be so, but we should keep in mind that M-Shwari is still a new service and it will take time for it to spread across the country. But spreading rapidly it is, as exemplified by the quadrupling of the aggregate deposit amount in less than three months. So let’s give it some time.

It is the other issue raised in the article that I find more concerning — Safaricom has a monopoly over mobile financial services in Kenya and I think that calls for the carrier to open M-Shwari to other banks, in addition to the Commercial Bank of Africa, are reasonable. “Safaricom is admired abroad”, The Economist reminds us, but it is the admiration of its Kenyan users that the carrier should be concerned with the most. And letting the banks compete for customers on its platform should lead to lower borrowing fees — always a consumer favorite.

Image credit: Technologybanker.com.