How the Viagra Spam Industry Works

The New York Times’ Andrew E. Kramer reports of a small group of Russian hackers who managed to build a system, which at one point was responsible for generating about a third of all global spam emails, hawking things like Viagra and male sexual enhancement products. The spammers profited from their scheme in two separate ways, both of them illegal. On the one hand, this “multimillion-dollar illegal enterprise with tentacles stretching from Russia to India” was capable of producing fake copies of the drugs that were being advertised, which were then used to fulfill the customers’ orders. At the same time, the criminals were infecting the computers of their customers — mostly Americans — with software, which would then be used to collect the victims’ credit card information. Several of the criminals have now been convicted of various offenses and are likely to spend some time in jail, but the spam hasn’t stopped; in fact, if my experience is anything to go by, Viagra-type of emails are on the rise.

So I thought it was time to revisit the issue of how such systems operate. In his piece, Kramer alludes to a University of California, San Diego study from a couple of years ago, which closely analyzed the spam-based business and quotes one of its authors. But he doesn’t really go into much detail about the researchers’ findings, which are incredibly interesting. Digging deep into the origins of spam, the scientists found that behind the vast majority of emails promoting all these cheap sexual enhancements and designer goods are but a handful of banks and suppliers. Moreover, these are all well known. And yet, such operations have proved impossible to eradicate. Let’s take another look at what makes them so enduring.

How Spam Works

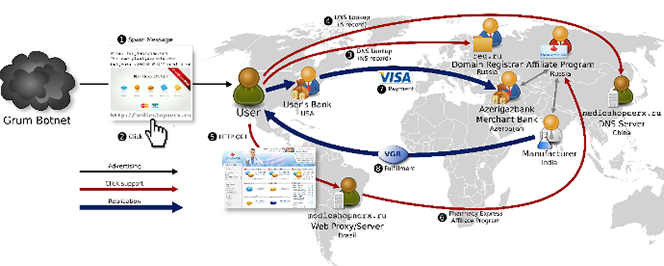

The researchers draw on the findings of a group of investigative journalists, who explored the market structure for illegal pharmaceuticals sold online through the “Behind Online Pharma” project. They identified three main components of the scheme:

1. Advertising

In the fake pharma world, advertising can take several different shapes. The most prominent one is email spam, but it can also include spam on blogs and social media platforms, search engine optimization (SEO), and even sponsored advertising. The researchers note that the introduction of IP blacklisting of email spam senders has only pushed spammers into developing more sophisticated delivery vehicles. Moreover, there are now specialized operators to whom spamming can be outsourced (we’ve recently discussed the “Cybercrime-as-a-Service” marketplace in some detail). In any case, preventive measures have been ineffective and, as Kramer notes, about 70 percent of all global email is still spam.

2. Click Support

Once the huge volumes of spam ads have been delivered, a fraction of the recipients would respond by clicking on a URL and will then be redirected to the spammers’ website. In order to achieve this seemingly straightforward objective without being caught by the authorities, the spammers are forced to go into great lengths. And they do! One of the evasive tactics is the use of redirection sites. See, advertising the end URL in the spam email may be counterproductive, because that URL would often be blacklisted. Instead, the spammers would advertise a totally unrelated URL, which they may have hijacked, and so thwart their adversaries.

Another layer of the “click support” component of the spam infrastructure involves domain ownership. The researchers have found that spammers can buy domains either directly from a registrar or from a reseller, known as “domaineer”, who purchases domains in bulk for the purpose of selling them to the underground community, often as part of a “start-up package”. Intervention here has proved difficult, because registrars “appear indifferent to complaints”.

Furthermore, to do their thing spammers need dependable domain servers (DNS) and web servers, both of which are liable to takedown requests. In response, a specialized industry has evolved, which offers “bulletproof” hosting services.

The final link in the click support chain are the online stores, which accept the customers’ orders. Typically, these are operated by entities, which are independent from the email spammers. In fact, we learn that spammers often work as affiliates of such stores, collecting a commission of about 30 percent – 50 percent of the sales amount for their efforts.

3. Realization

For the whole scheme to work, the scammers must be able to accept payments for their illegal products and ship them to the customer’s destination, which may well be halfway around the world. Now, as most of the customers are located in the U.S., credit card support is essential. Yet, accepting card payments for such things is not a mean feat. As the researchers note, correctly, Visa and MasterCard impose restrictions on their member banks and processors and offenders may be heavily fined or thrown out of the associations altogether. Yet, such pressure has proved inadequate. The study finds that, amazingly, 95 percent of all spam-related credit card transactions are processed by only three banks, based in Azerbaijan, St. Kitts and Nevis and Latvia. Moreover, spam processors tend to specialize in specific niches:

In particular, most herbal and replica purchases cleared through the same bank in St. Kitts (a by-product of ZedCash’s dominance of this market, as per the previous discussion), while most pharmaceutical affiliate programs used two banks (in Azerbaijan and Latvia), and software was handled entirely by two banks (in Latvia and Russia).

As you can see, most, but not all, processors are located in places with lax regulation.

The fulfillment of orders for counterfeit pharmaceuticals, replica goods and other physical products is handled by big business-to-business e-commerce companies, like China’s Alibaba, which offer highly dependable direct shipping services (called “drop shipping”) to affiliate programs. Here is an example of the “spam value chain” from empirical data used in the study:

How to Combat the Spammers

The researchers then examine possible defensive strategies that could be employed against the spammers and conclude that the best approach would be to prevent the spammers from being able to take payments for the things they sell. As they put it:

[T]he payment tier is by far the most concentrated and valuable asset in the spam ecosystem, and one for which there may be a truly effective intervention through public policy action in Western countries.

So, if an issuing bank were to refuse to settle certain types of transactions with the banks identified as providing payment processing services to spammers, the whole criminal structure would crumble, as it would find itself unable to monetize its operations. Moreover, the researchers contend, for most spam-advertised products (for example, regulated pharmaceuticals, replica products and pirated software), such an enforcement action would have a legal basis.

Yet, there is a rather big problem with this approach. See, I just don’t see Visa or MasterCard banning one or several of their member banks from processing certain types of transactions, which other members are perfectly free to engage in. And as issuers cannot make such decisions on their own, the alternative would be for such a black list to be created by a governmental agency. Well, in my original of the paper, I wrote that “spam emails just don’t strike me as the type of issue likely to capture the collective imagination of financial regulators right now”. That was true back then and I believe it still is.

The Takeaway

So, I think that we should prepare ourselves for living with the relentless onslaught of Viagra emails for quite some time to come. If there is good news, it is that the big email providers like Google and Yahoo have become good enough at identifying spam mail, so as to send it directly into our spam folders. I guess that’s as well as anyone can do for now.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.