How the CARD Act Saves Us $3.5 Billion a Year in ‘Other Fees’

Last week I reviewed the CFPB’s report on the effect the CARD Act of 2009 has had on the cost of credit cards in the U.S. In all, between 2008, the year before the Act began coming into effect, and 2012, credit cards became cheaper by almost two percentage points, the CFPB has found. Much of the decline was the result of two developments: the virtual elimination of the over-the-limit fees, which resulted in annual savings of $2.5 billion, and the reduction of the overall amount of late fees paid by cardholders, which added an additional $1.5 billion in savings. The total amount of annual fees collected by card issuers increased, but only by $475 million a year, so the aggregate amount of consumer savings from these three major fee categories came to about $3.5 billion, give or take.

But, it turned out, there was another group of lower-profile credit card fees, whose total was pushed down by the CARD Act by as much as the total of the three major fees. These “other fees” include charges for debt suspension (these make up about 45 percent of all “other fees”, by dollar amount), balance transfers (25 percent), cash advances (20 percent), returned payments and other transactions. The amount of “other fees” paid by American consumers declined from $2.0 billion per quarter in 2008 to $1.1 billion per quarter in 2012, for a total of about $3.5 billion. Let’s break that total down.

Suspension Fee Total down by 41%

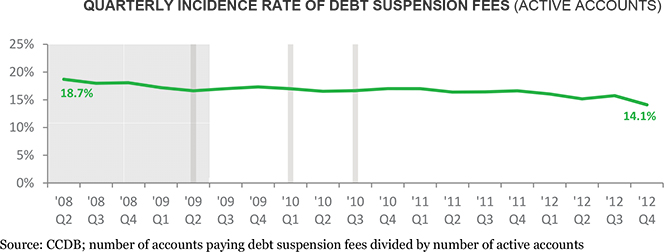

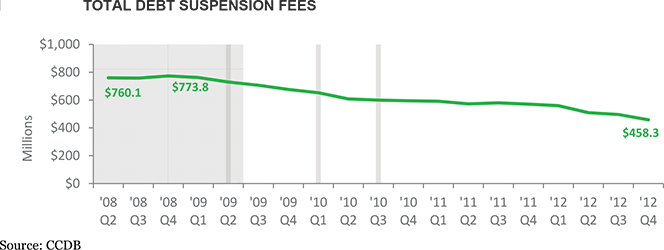

Consumers enrolled in debt suspension and debt cancellation services are typically charged a monthly fee, which varies with the size of the balance at the end of the month. The quarterly incidence rate of debt suspension fees has declined from 18.7 percent in 2008 Q2 to 14.1 percent in 2012 Q4. The reduction was similarly large among consumers with core and deep subprime credit scores — from about 18 percent in 2008 Q4 to about 12 percent in 2012 Q4, whereas the super-prime group saw a much smaller decrease — to 4.6 percent in 2012 Q4 from 5.2 percent in 2008 Q4. The incidence rate fell the most — by 250 basis points — between 2011 Q4 and 2012 Q4.

In dollar terms, the quarterly volume of debt suspension fees has declined from $773.8 million in 2008 Q4 to $458.3 million in 2012 Q4, a drop of 41 percent. The decline is the result of the reduction in the total number of accounts, the fall of the incidence rate in accounts paying debt suspension fees, particularly among cardholders with subprime credit scores, and the average balance per enrolled account. The biggest decline in the volume of debt suspension fees was measured in 2009, which the researchers believe may be the result of a reduction in the number of accounts due to the recession.

Balance Transfer Fees down by 26%

Balance transfers give cardholders the opportunity to pay a lower interest rate on their outstanding card balances for a limited period of time — typically between 6 and 18 months. However, consumers are generally charged a fee when they transfer balances from one issuer to another, which is calculated as a percentage of the transferred amount and usually comes with a floor and / or a ceiling.

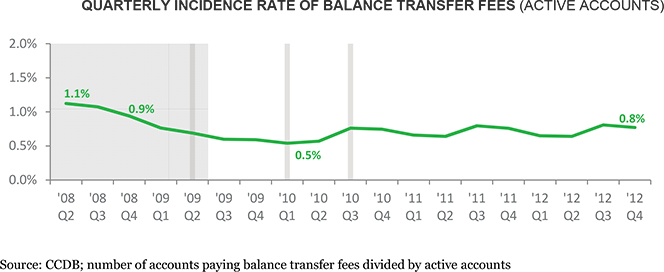

The quarterly incidence rate of balance transfer fees declined from 0.9 percent in 2008 to Q4 to 0.8 percent in 2012 Q4, although it had reached a trough of 0.5 percent in 2010 Q1.

The total volume of transferred outstanding balances fell from $33.6 billion in 2008 Q4 to $14.1 billion in 2009 Q4, and has remained roughly at that level through 2012, we learn.

The researchers suggest that the steep decline of the balance transfer total “may indicate a reduced appetite for debt transfers due to the recession”. However, it seems clear to me that the sharply increased balance transfer rate, by deterring consumers, should also have something to do with it. As you see in the chart below, the balance transfer rate rose from 1.3 percent of transferred amount in 2008 Q4 to a peak of 2.7 percent in 2010 Q3, before falling to 2.0 percent in 2012.

Cash Advance Cost up by 20%

Issuers typically charge a fee when consumers use their credit cards to obtain cash at an ATM or from a bank teller. The cash advance fee is calculated as a percentage of the transaction amount, often with a floor.

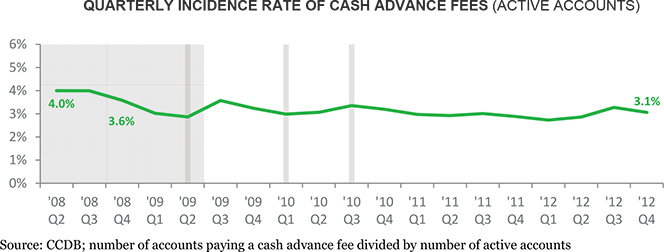

The quarterly incidence rate of cash advance fees declined slightly from 3.6 percent in 2008 Q4 to 3.1 percent in 2012 Q4.

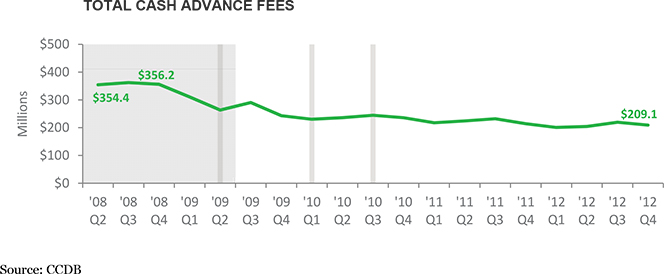

The total amount of cash advance fees also fell — a result of the modest decline of the incidence rate, a decrease in the number of accounts, an overall declining portfolio (the volume of cash advances fell from $9 billion in 2008 Q4 to about $4 billion in 2012 Q4, we learn), as well as a reduction of 30 percent in the per-incident cash advance size.

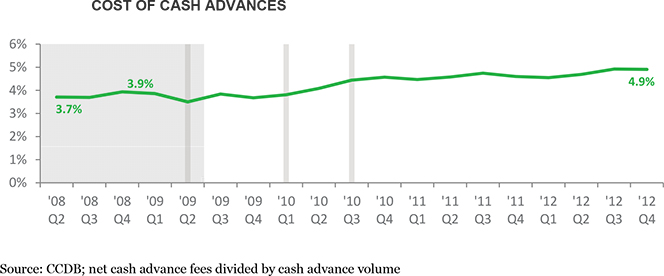

The total amount of cash advance fees fell less rapidly than the overall volume of cash advances, as the issuers raised the cash advance rates. As shown in the chart below, the cost of the average cash advance rose from 3.9 percent of the advanced amount in 2008 Q4 to 4.9 percent in 2012 Q4.

The Takeaway

So, on the whole, the CARD Act has effected a significant reduction in our overall cost of using credit cards. The CFPB’s report doesn’t calculate the total amount we’ve saved, but a recent NBER paper, which I reviewed last week, estimates that the legislation has reduced Americans’ overall borrowing costs by 2.8 percent of our aggregate daily balances, saving us $21 billion a year in the process. That’s a lot of money.

Image credit: Flickr / Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.