How Are Free Checking Accounts Faring?

That is the question Richard J. Sullivan from the Kansas City Fed has tackled in a new paper. It is the first systematic attempt to analyze the effects of the cap on debit interchange fees, which went into effect in October 2011. As regular readers know very well, Congress, through the passing of the Durbin Amendment to the Dodd-Frank financial overhaul legislation, directed the Federal Reserve to ensure that debit interchange fees were “reasonable and proportional” to the cost of processing of debit card transactions. The Fed responded by ruling that card issuers with consolidated assets of $10 billion or more could not receive a fee that exceeds 21?ó plus 0.05 percent of the transaction amount, plus 1?ó for implementing certified fraud-prevention programs. Smaller banks, however, were exempted from the new rule. In all, the imposition of that limit translated into an annual revenue loss of about $7 billion (estimates vary) for non-exempt issuers.

Given these huge revenue shortfalls, Sullivan reminds us, there were concerns that affected banks might try to offset their losses by raising more revenue from checking accounts, for example by introducing monthly fees. On the other hand, the author notes, exempted banks might have attempted to take advantage of their privileged position and attract new customers by reducing or eliminating fees. Well, the author finds that, on net, “consumers actually had increased access to free checking after the debit card regulations went into effect in late 2011”. Let’s see what lies behind this conclusion.

Free Checking Accounts on the Rise

The author’s sample data sets include 41 non-exempt banks, with $548 billion in combined assets, which accounted for 58 percent of all checking account deposits at the end of 2010. In contrast, the 240 banks in the exempt sample held $15.4 billion in combined assets, or 1.6 percent of all checking account deposits. Sullivan is confident that these samples are representative for their respective groups and I see no reason to doubt it.

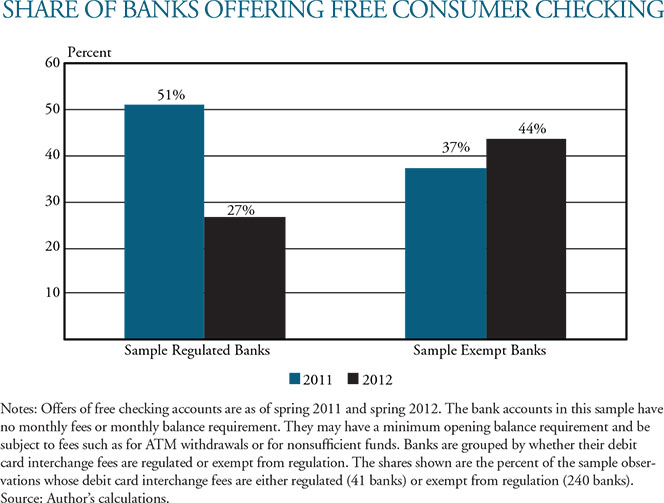

Sullivan’s analysis shows that regulated banks mostly raised fees on checking accounts, whereas most exempt banks reduced theirs, in the process more than offsetting the impact of regulated banks’ raising of fees. In the regulated sample, the share of banks offering free checking accounts declined sharply, from 51 percent in 2011 to 27 percent in (see the chart below). By contrast, in the exempt sample, the share offering free checking increased from 37 percent in 2011 to 44 percent in 2012.

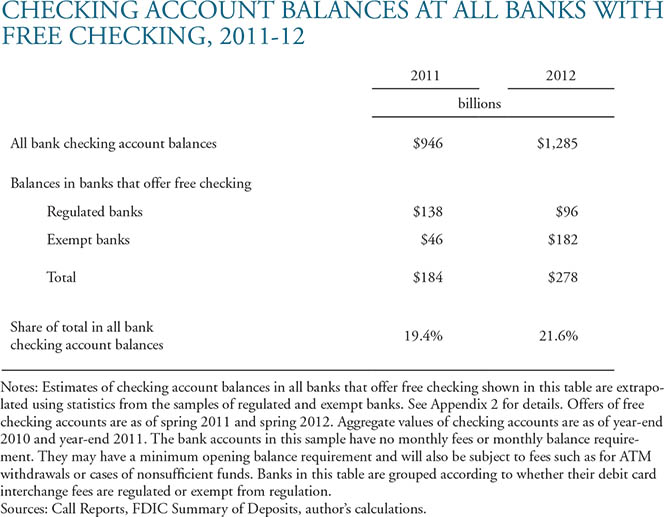

Sullivan argues that the relatively small increase in the share of exempt banks which offer free checking accounts to consumers had an outsized effect on the overall availability of free checking. The reason is that the volume of checking account balances held in banks which offer free checking, as a share of all checking account balances, rose from 19.4 percent in 2011 to 21.6 percent in 2012. In dollar terms, the increase was from $184 billion to $278 billion.

Conditionally-Free Checking Accounts Are also Increasing

Conditionally-free accounts are those, which allow customers to avoid monthly fees by meeting certain requirements, typically a minimum-balance requirement, a usage requirement, or both. Balance requirements involve a minimum daily balance or a minimum average balance, or both. Usage requirements stipulate a minimum on the numbers of debit card payments or an automated deposit with a minimum dollar value, or both. As with free accounts, conditionally-free accounts usually involve an opening balance requirement or fees such as for ATM use or for insufficient funds.

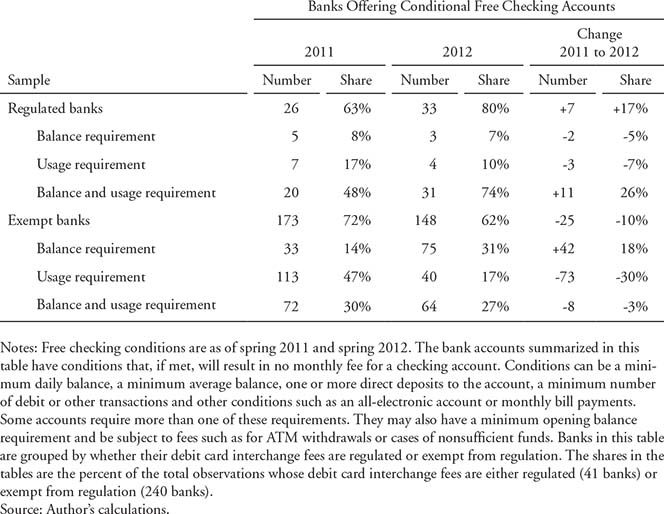

Sullivan finds that, in contrast to free checking, the availability of conditionally-free accounts increased among non-exempt banks and declined among banks in the exempt sample. The share of regulated banks, which offered such accounts increased by 17 percent, from 26 banks in 2011 to 33 banks in 2012 (see the table below). The share of exempt banks offering conditionally-free accounts fell by 10 percent, from 173 in 2011 to 148 in 2012. Given the results from the free checking account products, the obvious conclusion is that, while some regulated banks have shifted from unconditionally- to conditionally-free accounts, the reverse was true at exempt banks.

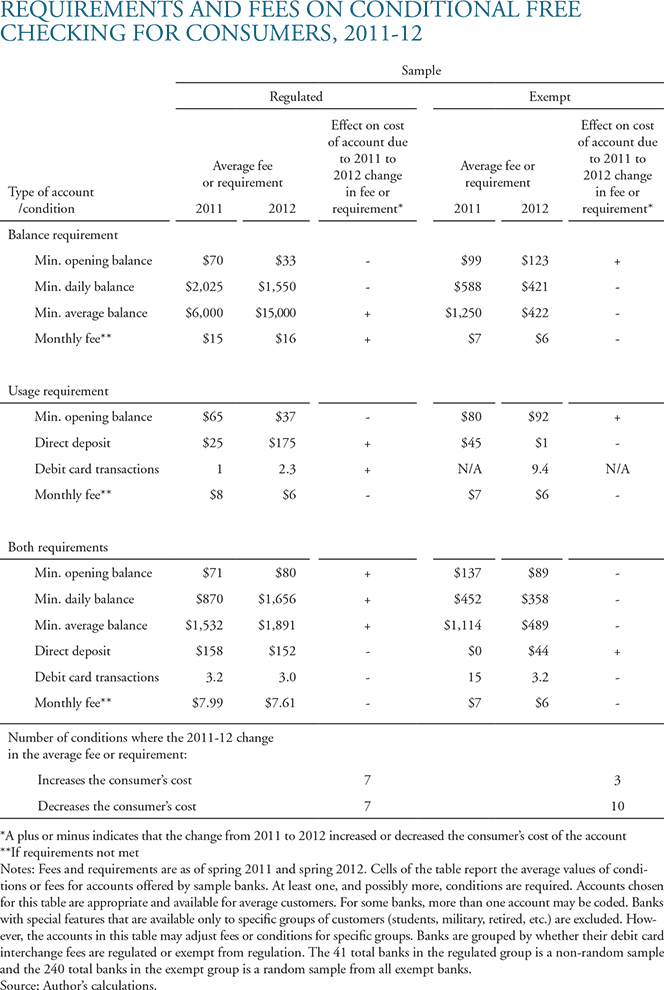

Changes in the requirements on conditionally-free accounts were mixed across banks. Some of them increased the usage or balance requirement, while others lowered them. As Sullivan notes, the importance of the change to consumers depends on how they use their account. For those who cannot meet a minimum balance, for example, the most important fee might be the resulting monthly fee on the account. Among non-exempt banks, the monthly fee for an account with only a balance requirement increased from an average of $15 in 2011 to $16 in 2012. However, the average monthly fee in the other five type-of-account and sample combinations of the conditionally-free accounts declined from 2011 to 2012, along with the cost to consumers (see the table below). Overall, the cost of monthly fees to consumers seems to have declined.

The Takeaway

Here is Sullivan’s conclusion:

Interchange fee regulation has led to significant changes in the extent to which free checking accounts are available to consumers and, in many cases, to changes in the requirements under which conditional free checking accounts are offered. Several key factors appear to have driven banks’ decisions. Regulation of interchange fees for debit card payments eliminated roughly $8 billion of revenue at regulated commercial banks. Such a large change led many regulated banks to drop free checking. Some exempt institutions may have seen the regulation of interchange fees as an opportunity to drop free checking and earn added revenue from deposit services. However, more exempt banks, particularly larger exempt banks—those with strong loan demand and a need for additional funding—decided to add free checking.

For an average consumer, free checking became more available after interchange fee regulation.22 The footprint of banks offering free accounts rose from 19.4 percent of all checking account balances in 2011 to 21.6 percent in 2012. Elimination of free checking accounts at larger, regulated banks was more than offset by an increase in free checking accounts at smaller, exempt banks. While generally more available, a consumer who wants free checking may have to switch to a smaller bank.

Changes to another major category of checking account products, conditional free checking, are less clear but are similar to changes in unconditional free checking. Conditional free checking became somewhat more expensive and more complex at banks in the regulated sample but less expensive and less complex at banks in the exempt sample.

I think that this will not be the last study of the issue.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.