Do We Really Care about Credit Card Security?

Over the past month or so we’ve had a couple of big data breaches at large U.S. retailers. First, in the middle of December, Target — the second-largest retailer in the United States — reported that the credit and debit card accounts of as many as 40 million of its customers had been compromised. Then last week, high-end retailer Neiman Marcus told us that hackers had managed to install “malicious software” in their system, which had been used to collect the information of 1.1 million credit and debit card accounts.

And now the FBI is telling us that it had discovered about 20 data hacking cases in the past year that involved the same type of malicious software used against Target and is warning us to prepare for more cyber attacks to come. In fact, the FBI has gone as far as to distribute “a confidential, three-page report to retail companies… describing the risks posed by “memory-parsing” malware that infects point-of-sale (POS) systems, which include cash registers and credit-card swiping machines found in store checkout aisles”.

But, while there can be no question that retailers are very worried about the security of their payment processing and data storage systems, consumers’ attitude toward data security is, it turns out, much more nuanced. In a newly-released paper, Joanna Stavins of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston finds that, for established payment methods like credit cards, consumers’ perception of security does not influence adoption, although it does affect actual usage.

And there is a good reason for consumers’ more relaxed approach to data security, as compared to the retailers’: whereas merchants actually suffer losses when fraud is committed at their stores, consumers are fully protected. Of course, no one looks forward to cleaning up his credit card account after it’s been compromised, but issuers typically resolve such issues proactively by replacing all affected cards and changing their account numbers and security codes. I am fairly confident that very few consumers whose cards have been hacked during the recent data breaches would suffer any inconvenience, never mind a loss. That being the case, why would they be concerned? But let’s take a look at Stavins’ findings.

On Security and Payment Adoption

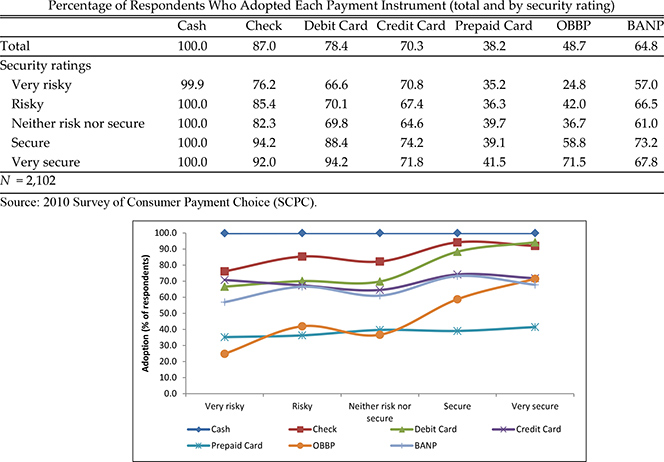

For some payment instruments, Stavins finds, adoption shows no correlation with security. For credit cards in particular, the correlation was found to be absent altogether. Within each sub-sample (that is, consumers who rated credit cards as “very risky”, “risky”, etc.), about two-thirds of people adopted credit cards, the author tells us. However, as you can see in the table below, that is not at all true for debit cards and online bank bill payments. Whereas only two-thirds (66.6 percent) of those who considered debit cards “very risky” adopted them, the share rose to 94.2 percent among those who considered them “very secure”.

On Usage and Payment Adoption

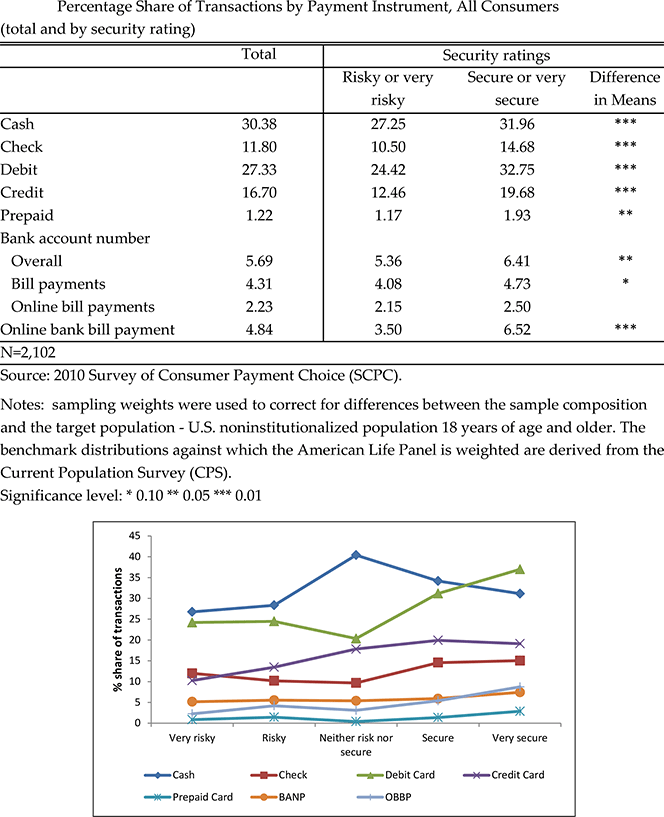

However, the link between security and usage of payment methods is plainly evident in the table below. For every payment method, Stavins finds, consumers who consider it secure or very secure use it more intensively than those who consider it risky or very risky. The author is quick to add that this correlation between security perception and payment use does not imply causality, but she does not offer an alternative implication, either.

On Security and Location

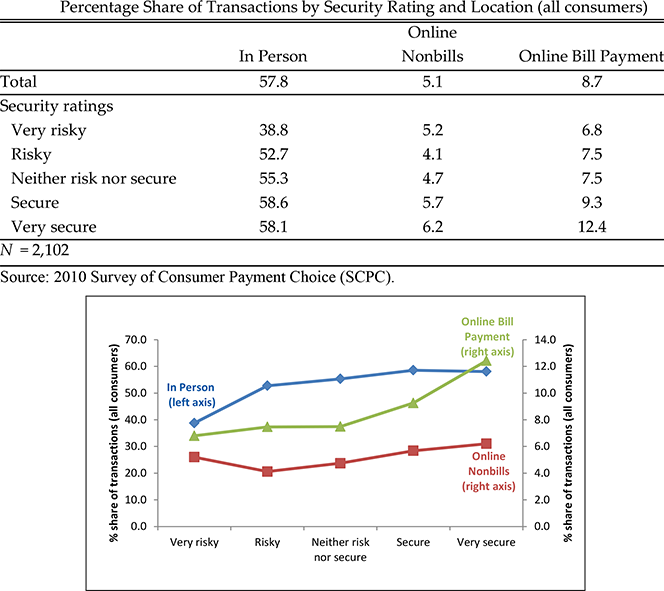

The location of transactions (online vs. offline) was found to matter to consumers, regardless of the type of payment method used. Respondents who rated online transactions as very secure paid a significantly higher share of their bills online (12.4 percent), compared to consumers who rated online transactions as very risky (6.8 percent).

PIN vs. Signature Debit

Every time you use your debit card, the payment can be processed in one of two ways. PIN transactions, Stavins reminds us, are routed through an electronic funds transfer (EFT) network (e.g., Star, NYCE, Pulse). Signature debit transactions, in contrast, are authorized and settled through the same Visa and MasterCard networks used for credit card transactions.

The important difference, at least as far as our present exercise is concerned, is that the two types of debit card transactions differ in terms of expected losses resulting from fraud or theft. PIN debit transactions are considered more secure because the consumer authenticates her card with a pre-selected PIN. Signature debit transactions cannot be as easily authenticated, not least because many merchants waive the signature requirement for small-value payments at the point of sale (POS).

Moreover, the signature debit process is used in card-not-present transactions, such as online, mail or phone payments, where the likelihood of processing fraudulent transactions is greater. Consequently, in 2011, PIN debit card fraud losses were estimated at only $0.004 per transaction, while the average for signature debit card fraud losses was eight times as high — $0.031 per transaction. In percentage terms, signature POS fraud losses averaged 0.08 percent, while PIN POS fraud losses averaged 0.01 percent.

Crucially, however, card issuers’ losses do not imply that consumers suffer the same losses. In fact, a cardholder is liable for no more than $50 per PIN debit transaction if she reports the fraudulent transaction within a specified period of time. Visa and MasterCard have gone even further, offering the same zero-liability protection against unauthorized transactions as they do against fraudulent credit card transactions. For card-not-present transactions, if card issuers do not provide a way for merchants to identify the cardholder, consumers do not face any liability. So, even though signature debit cards carry higher fraud losses than PIN debit cards, consumers are well protected against incurring those losses.

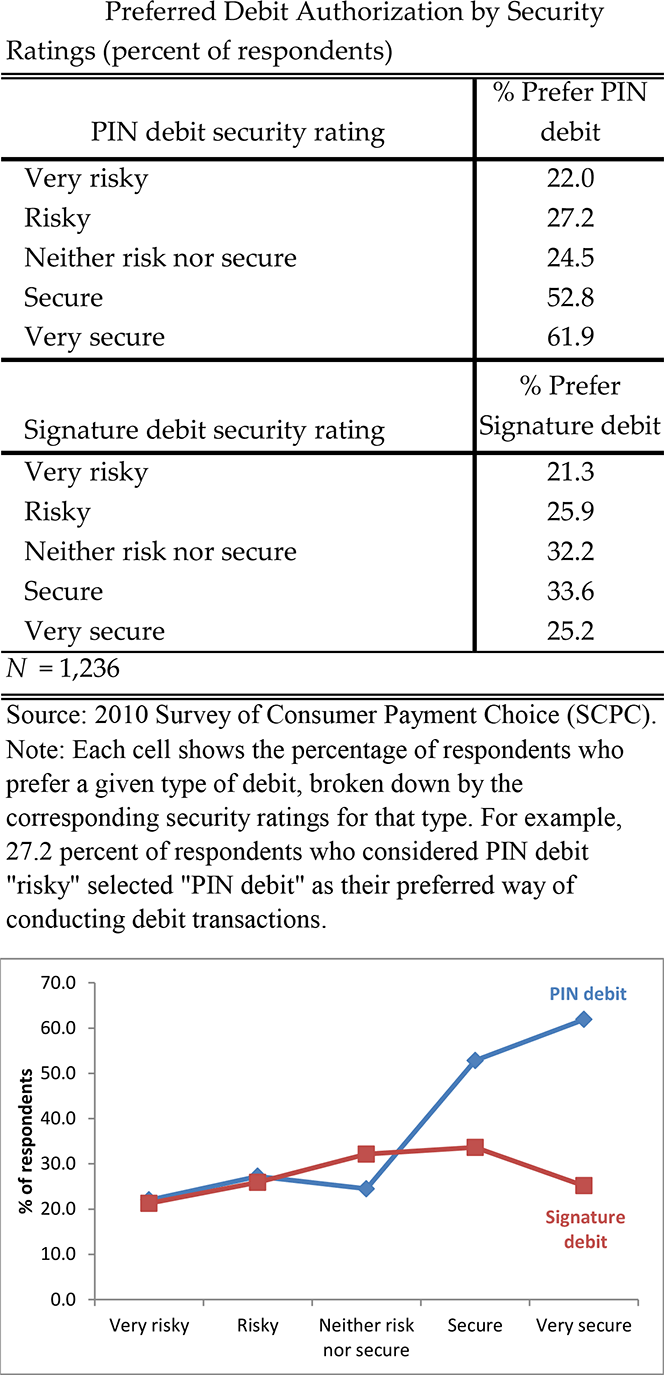

Nevertheless, irrespective of who bears the loss, consumers’ assessments are consistent with the evidence that PIN debit is more secure than signature debit: 63.8 percent of respondents consider PIN debit secure or very secure, compared with 51.4 percent for signature debit. This divergence is illustrated in the table below, which compares security ratings of PIN and signature debit to the stated preferred way. As you see, consumers who consider PIN debit?á “secure” or “very secure” are at least twice as likely to prefer PIN debit as those who consider PIN as “risky” or “very risky”. Moreover, even consumers who consider signature debit “very secure” are less likely to prefer signature debit over PIN debit at the checkout.

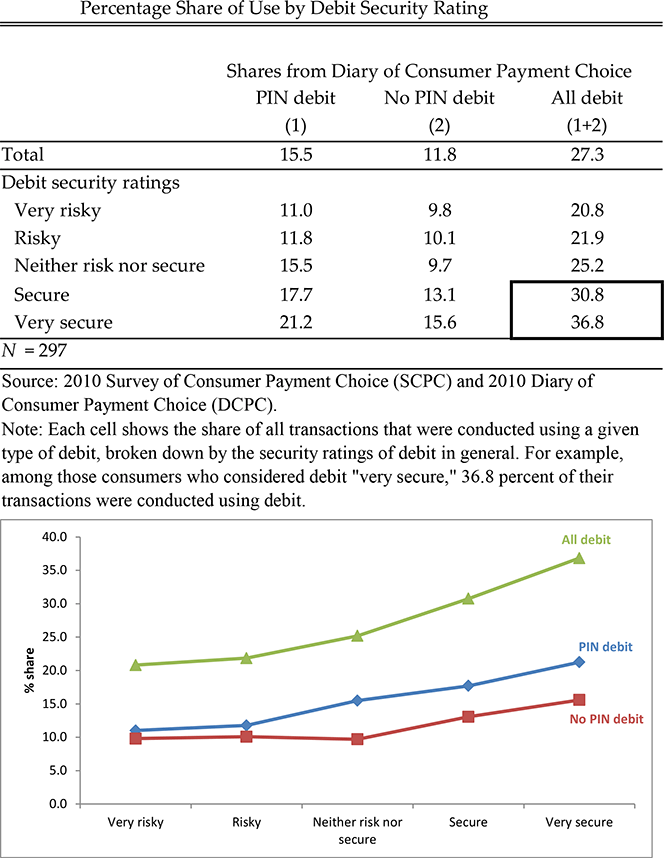

It should come as no surprise that consumers who consider debit secure or very secure tend to use debit cards more intensively than those who consider it more risky. The pattern is apparent in the case of total debit, PIN and no-PIN (signature) debit, as seen in the table below. The author is quick to point out, however, that the correlation between consumers’ security assessment and use may be affected by several factors and, anyway, consumers may not have a choice as to what type of debit the merchant accepts. For example, in online or phone payments, signature debit is the only option.

The Takeaway

Consumers consistently cite security as the most important attribute of payment methods, the report notes, but their decisions on whether or not to adopt and use a certain type of payment are only modestly affected by their assessment of its security, mostly because they see not much difference in security among the various payment methods. Stavins:

Security can be interpreted differently by different people. Respondents who are more concerned about their financial loss (those who view cash as risky) are more likely to adopt bank account number payments, while those who are more concerned about loss of their personal information (those who view cash as secure) are less likely to adopt bank account number payments.

Image credit: Iitpro.co.uk.