Affirming Your Intention to Pay and the Bane of Debt Collection

If the headline doesn’t make much sense to you, just bear with me for a minute. A couple of years ago, a start-up called Kwedit enabled users to receive virtual goods immediately if they promised to pay for them later. No immediate payment was required, just a promise. If you kept your word, you would be allowed to borrow larger amounts of money for your next purchases (initially you could only borrow up to $5). How did Kwedit do? Well, at some point the start-up told us that only about 33 percent of the payment promises were being kept and, in due time, the company folded.

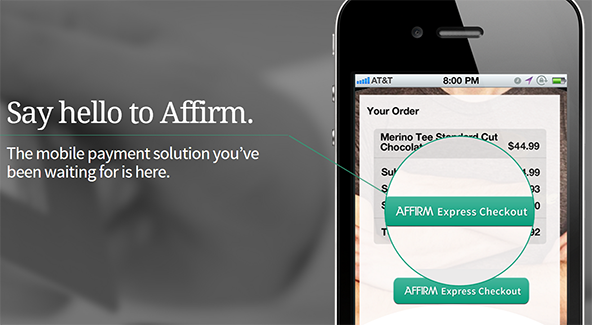

But why am I telling you the sad story of a little-known start-up, which, in hindsight, was doomed to fail? Well, this morning, Reuters informed me that a famous entrepreneur had just launched a start-up that seems to be doing something very similar to what Kwedit did, only on a more ambitious scale. On cue, Felix Salmon has reviewed Affirm — the start-up in question — and is mildly skeptical about its prospects. I share his skepticism, only mine runs deeper due to a side effect, which has escaped Salmon’s attention, but is certain to afflict Affirm, if the start-up manages to survive its initial growing pains. I’m talking about the collection efforts, in which Affirm will inevitably have to engage on a regular basis and the negative publicity these efforts are sure to produce. Let me elaborate.

What Is Affirm?

First, though, let’s take a look at what Affirm does. Here is how the start-up explains its raison d’?¬tre on its website:

You were ready to buy, but not ready to pull out your credit card in the middle of the coffee shop. You had five minutes to kill, which was enough to find some cute open-toes for your favorite sundress, but not enough time to actually complete the purchase. You found the Giants tickets you wanted, but it might be a little suspicious if you pulled your wallet out in the middle of the weekly operations meeting. Our phones make it so easy to shop, but why is buying so hard?

Leaving aside the highly dubious proposition that five minutes are “enough to find some cute open-toes”, this is where Affirm comes to your rescue:

Affirm brings Two Tap purchase to the sites you shop every day. No fumbling with a credit card, battling autocorrect on a billing form, or downloading any apps. It’s time to turn your phone from a mobile shopper into a mobile buyer. Tap. Tap. Buy.

Having solved your odious problem of not having five minutes to complete an impulse purchase, Affirm is generous with the debt repayment terms, because they “know you’re good for it”:

Buying with Affirm is not only effortless, but you also have thirty days to pay us back. When you’re back at your desk — when you’ve got more time — we provide a lot of ways we can settle your bill. And you won’t pay any fees. Affirm aspires to create a magnificent experience and help you fall in love with buying on your phone.

Now, am I the only one to wonder how exactly Affirm has solved the dreaded time deficiency problem, if the time it “saved” you will eventually be spent in making the repayment? But let’s move on the issue of how the start-up generates revenue, if its service is free for users? The company explains in its Terms of Service:

Affirm currently is free to use for users making purchases. Affirm makes money by reducing friction in the buying process, thereby increasing sales for merchants. Affirm charges merchants for this service.

No pricing details have been released, but, as Salmon explains, Affirm’s fee structure is likely to be easily accepted by merchants:

Merchants already pay an interchange fee so that they can accept credit cards as payment; paying a similar fee to Affirm will surely be worth it, if they can convert a greater percentage of shopping carts into actual purchases.

Still, it wouldn’t hurt if Affirm had disclosed its fees.

The Case for Skepticism

Salmon has identified a weakness in the start-up’s business model:

Obviously, Affirm needs to know who you are, and where to find you, so that it can invoice you for the stuff that you’ve bought online. And if you do end up being rejected when you try paying with the Affirm button, then the worst-case scenario is that you’re just back to the?ástatus quo ante, forced to pay with a credit card or similar. Still, people don’t like being instantly profiled as untrustworthy; the problem, of course, is that it’s?áprecisely?áthe untrustworthy people with no intention of paying who are likely to be flocking to Affirm in an attempt to order free stuff.

Indeed, that is precisely what happened to the aforementioned Kwedit. And what would Affirm do with those refusing to pay, of whom, if Kwedit’s experience is anything to go by, there would be many? The company explains in the “Collection Methods” section of its Terms of Service:

You agree to allow Affirm to send you payment reminders from time-to-time. These reminders may take the form of any available communication. You also acknowledge that Affirm or any of its affiliates has the right to contact you by any available means in order to obtain your payment. [Emphasis added.]

Now, that is a recipe for disaster. See, irrespective of the start-up’s undisputed right to collect unpaid bills, any collection efforts it may undertake are bound to cause a backlash, however mild-mannered and law-abiding Affirm’s debt collectors may be. It is not a question of if, but of when it would happen and when it does, the damage may be irreparable.

The Takeaway

Whatever Affirm’s website may say, a sizable share of the start-up’s customers will not be good for the credit they are given and the company is bound to have a high rate of delinquent payments. So, in order to become and remain a viable business, Affirm will have to rely heavily on debt collection efforts and that is where its biggest problem lies. The reality is that no one likes debt collectors and it could only take one debt collection terror story, whether real or fictitious, to go viral on Facebook or Twitter to cause Affirm to go the way of Kwedit — that is if it hadn’t done so even before that.

Image credit: Affirm.com.