How Do You Like Your Prepaid Card?

This is the broad question, which yet another recent prepaid card study has attempted to answer. This one is the work of Fumiko Hayashi and Emily Cuddy — researchers from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Once again, the researchers’ interest falls squarely on one specific type of prepaid card — the general-purpose reloadable (GPR) card — which, the researchers tell us, has been gaining the most traction among consumers with no access to more traditional payment instruments, such as debit and credit cards.

Hayashi and Cuddy have addressed a long list of questions, including: How long do GPR card accounts typically survive? How often and in what amounts are the accounts loaded by cardholders or by third parties, such as the government? How often and in what amounts are debit transactions made each month? What proportion of debit transactions are making purchases, withdrawing cash, paying bills or transferring money between people? Where are purchase transactions made? What are the average number and value of fees incurred per month? How does prepaid card fraud typically occur? Which types of transactions have the highest fraud rates? Does the ticket size vary between fraudulent and non-fraudulent transactions? Well, let’s see how the researchers answer these questions.

GPR Prepaid Basics

First, let’s remind ourselves what GPR cards are. So, GPR is also known as an “open-loop” prepaid card. Its alternative — the “closed-loop” prepaid card — is a non-reloadable card that is typically sold by, and usable exclusively at, a given merchant or a merchant chain (for example, an Applebee’s or a Starbucks prepaid card).

Another big difference is that a closed-loop prepaid card cannot be issued to a specific consumer (meaning that anyone can use it), which is an option reserved for open-loop cards. Whereas a closed-loop card displays only the logo of the merchant at whose locations it can be used, an open-loop card displays the logo of the payment network, which is processing the payments made with it. In the U.S., these networks are Visa, MasterCard, Discover and American Express.

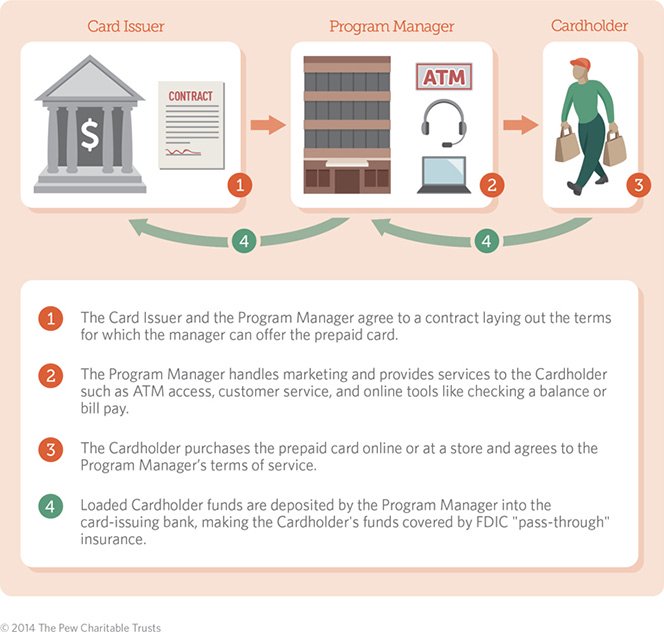

Here is a representation of the GPR payment process, from a Pew study, which we recently reviewed:

In case you wonder what the function of the program manager of our diagram is, Hayashi and Cuddy explain. While GPR prepaid cards are issued by depository institutions (i.e. banks), they tell us, program managers are the ones who are managing the prepaid programs for them. So, a program manager will consult with, and obtain approval from, the issuer in regard to the design and the fees associated with the card programs. Program managers also support the card issuance, delivery and distribution and may be responsible for providing customer service. Finally, one program manager can be managing prepaid cards issued by multiple financial institutions.

How Do We Like Our Prepaid Cards?

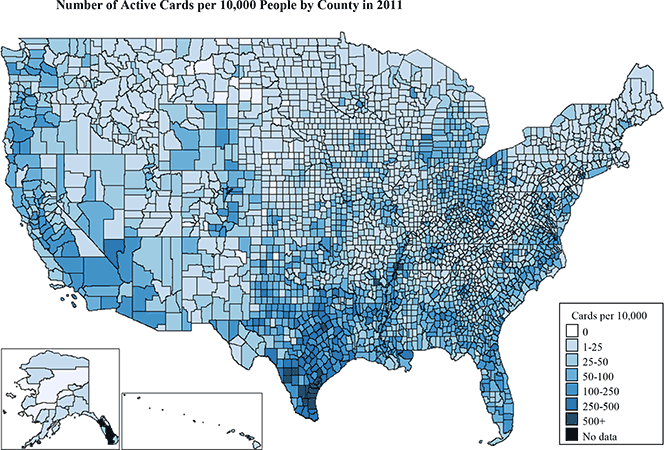

Hayashi and Cuddy analyze data provided by NetSpend — one of the biggest U.S. prepaid program managers. They begin by giving us this visual representation of GPR prepaid “penetration rates” across the U.S.:

Unsurprisingly, the researchers find that penetration rates of GPR prepaid cards in their sample are higher in counties where the shares of unbanked and underbanked consumers are higher. Within these regions, they find that penetration rates in Texas are higher than in any other states. Furthermore, other socio-demographic characteristics, such as ethnicity, household structure and crime rates are found to be strongly correlated with penetration rates, which suggests to the authors that GPR cards are more widely adopted by “certain groups of consumers than others”.

Prepaid cards, the GPR variety included, are generally short-lived, with the median life span of the accounts in this sample being less than a month, we learn. About a fifth of prepaid cardholders have never reloaded their cards. However, the life span of the cards varies significantly by account characteristic. For example, cards with periodic direct deposits by the government survive for at least two or three years. These cards are also used more intensively.

Almost all of the cards were used for purchase transactions while only half of them were used for cash withdrawals, but these rates also varied significantly for different types of accounts in this study. Most purchase transactions on the GPR cards in the sample were for non-durable goods and services, such as groceries, gas and fast food. Compared with debit card transactions, the share of card-not-present (CNP) transactions is considerably larger, which the authors see as an indication that for some consumers prepaid cards provide the only way to make transactions over the internet, by phone or by mail.

When they examine the fees paid by the cardholders in their sample, the researchers find that, besides reload fees, users pay an average of about $14 per month. The number and amount of fees are positively correlated with the users’ debit activities, although they vary significantly by account characteristic.

Finally, the authors find that prepaid fraud rates are considerably lower for PIN transactions than for signature-based ones and, among signature transactions, fraud rates are much higher in a card-not-present environment. Furthermore, fraud rates for ATM transactions are higher than card-present signature transactions, but lower than CNP signature transactions. Counterfeit and lost-and-stolen cards are two major sources of fraudulent transactions, we are told. In fact, lost-and-stolen is the number one reason for fraud in the card-present environment, whereas counterfeit causes more fraud in the CNP setting. Fraud rates are typically higher for merchant categories that have larger shares of signature-based CNP transactions and lower for the ones with larger shares of PIN transactions, we learn.

The Takeaway

Here is how Hayashi and Cuddy interpret their findings:

Our results suggest that both account and local socio-demographic characteristics significantly influence the life span, the load and debit activities, the shares of purchase and cash withdrawals, and the average number and value of fees incurred per month, and that transaction and merchant types influence the rate of fraudulent transactions.

For my part, I am most intrigued by the finding that the share of card-not-present transactions in the examined prepaid sample is much higher than it is for debit cards — prepaid’s closest relative. Prepaid, we now learn, is not only unique as the only payment card available to the nation’s unbanked population, but it also seems to have its unique uses.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.