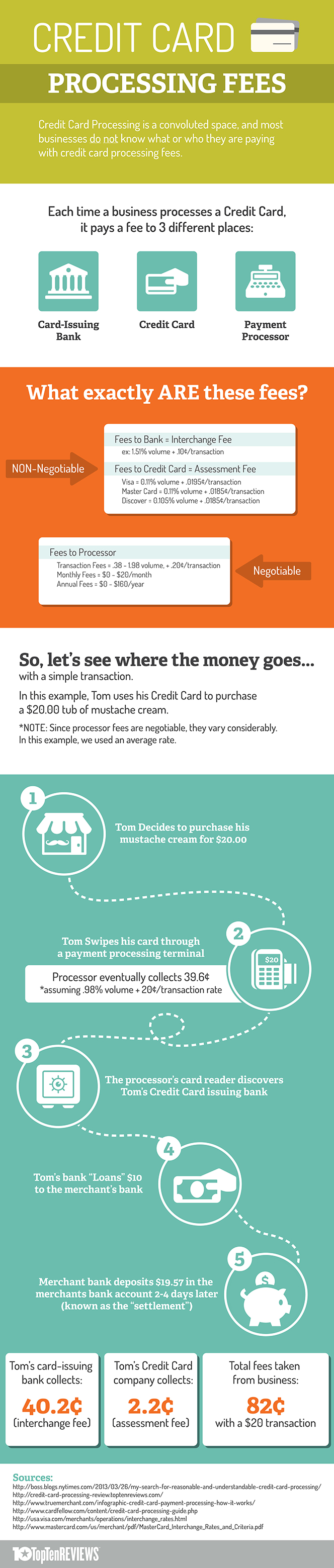

Where Do Your Credit Card Fees Go?

Over the past few months or so we’ve published a couple of infographics, which had attempted, with varying degrees of success, to break down into their constituent components the credit card fees paid by merchants. Of course, this blogger himself has also taken a crack at the issue on many occasions in the past, both in verbal communications with merchants and in blog posts, and can testify to the difficulty of achieving such a seemingly simple objective. The biggest problem lies in the multitude of rates (the infamous interchange rates), which Visa and MasterCard use to calculate the amount their card issuers should collect for each transaction.

Well, this morning I stumbled into yet another infographic dedicated to the same topic, whose authors, I think, have done a somewhat better job than the creators of the two graphs I mentioned earlier. More importantly, however, I think that, by offering different views at this issue, we will help a wider range of people grasp the underlying concept. And this is important, as I’ve seen even merchants doing more than $100,000 in monthly processing volume select the wrong pricing model, and pay dearly for their error. So let’s do this once again.

In Search of Simplicity

So, as you will see in the infographic below, a merchant’s credit card processing fees are made up of three separate components (for the sake of simplicity, I’ll leave Discover out of the picture):

- Interchange fees — these are set by Visa and MasterCard, are non-negotiable and are collected by the card issuers. In the wake of the Durbin Amendment, the Federal Reserve capped the debit interchange rates to a maximum of 0.05 percent of the sales amount, plus 21?ó per transaction and an additional 1?ó can be added for fraud prevention measures implemented by the bank. However, credit card interchange fees are left, for now at least, entirely to the discretion of the two card associations.

- Assessment fees — inaptly called “fees to credit card” in the infographic, these are also set by Visa and MasterCard and are non-negotiable, but are collected by the two credit card associations themselves. The assessment fees (the best way to look at them is as “association fees”) for both Visa and MasterCard are set at 0.11 percent of the sales amount.

- Processing fees — these are set and collected by the payment processor with whom the merchant has a direct relationship and are negotiable (for a change).

Now, it is important to recognize that, as a merchant has direct dealings only with its payment processor, and as that processor is the one doing the selling of the service, it falls onto the processor to find the best way to present it. Look at it this way: Visa, MasterCard and their issuers will collect their interchange and assessment fees, whatever the processor decides to do, so they don’t care about the presentation. Evidently, they don’t care about the simplicity, or lack thereof, of their interchange structure, either. But the processor cares a great deal about it, for if a merchant perceives a given pricing model as too complicated, it will ignore it, even if that model is, objectively, more beneficial than the alternatives. Perception is indeed reality.

Here is an illustration of my point. Square, to pick a name at random, has famously embraced a flat-rate model, in which each swiped transaction, regardless of the card’s brand or type or any other factor, costs a merchant 2.75 percent of the sales amount. A non-swiped transaction costs 3.50 percent plus 15?ó. Simple, right? It is, but let’s compare Square’s swiped fee to a traditional processor’s interchange-plus pricing model (I’m using this model for comparison, because it is the only one, which a larger merchant would ever accept). Let’s assume that our merchant is charged 0.50 percent plus 15?ó above interchange by its processor, which is fairly reasonable. Here is what we find:

|

Card Type and Interchange rate |

Transaction Amount |

|||||||

|

$5 |

$10 |

$100 |

$200 |

|||||

|

Square |

Traditional Processor |

Square |

Traditional Processor |

Square |

Traditional Processor |

Square |

Traditional Processor |

|

|

Visa CPS/Retail, Debit — 0.05% + $0.21 |

$0.14 |

$0.39 |

$0.28 |

$0.42 |

$2.75 |

$0.91 |

$5.50 |

$1.46 |

|

Visa CPS/Retail — All Other — 1.51% + $0.10 |

$0.14 |

n/a |

$0.28 |

n/a |

$2.75 |

$2.26 |

$5.50 |

$4.27 |

|

Visa Credit/CPS Rewards 1 — 1.65% + $0.10 |

$0.14 |

n/a |

$0.28 |

n/a |

$2.75 |

$2.40 |

$5.50 |

$4.55 |

|

Visa CPS/Small Ticket — 1.65% + $0.04 |

$0.14 |

$0.30 |

$0.28 |

$0.41 |

$2.75 |

n/a |

$5.50 |

n/a |

As you can see quite clearly in this comparison table, Square’s pricing model saves a good deal of money for merchants processing very small-ticket transactions (think coffee shops and the like). However, as the sales amount increases, the savings quickly grow ever smaller until eventually the dynamics are reversed and the traditional processor’s interchange-plus model becomes the more cost-saving option. The higher the transaction amount, the bigger the traditional processor’s advantage. You should also note that the cost difference is especially stark in the higher-ticket debit transactions (and remember, there are no non-qualified fees in the interchange-plus model).

The other observation you should make is that the break-even point, at which the merchant’s processing costs of using Square and a traditional processor become equal, is reached at a very low transaction-amount level — somewhere in the neighborhood of $15, give or take. Above it, Square quickly becomes ever more expensive. And that model has become the standard for all Square clones. So much for the virtues of simplicity!

Now here is the infographic:

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.