Young Borrowers Are Good Borrowers

One of the key provisions of the CARD Act of 2009 was aimed at restricting access to credit cards for college-age borrowers. Responding to loud outcries against the “predatory practices” employed by credit card companies on college campuses and elsewhere, the legislators ruled that, once the CARD Act took effect, no person under the age of 21 could be issued a credit card unless the individual had a cosigner or submitted financial information “indicating an independent means of repaying any obligation arising from the proposed extension of credit”. So how well has the new arrangement been serving the youngsters?

Well, a new paper from Peter Debbaut, Andra Ghent and Marianna Kudlyak from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond is the first attempt to answer this very question and the authors’ conclusion may come as a surprise to the proponents of the no-credit-for-college-kids provision. The three economists have taken full advantage of what they call a quasi-natural experiment provided by the CARD Act and have found that, prior to the legislation’s enactment, youngsters under the age of 21 were far less likely to be delinquent or default on their credit cards than older borrowers. And following the enactment, under-21s who would have chosen to get a credit card early, in the absence of the Act, were found to be less likely to get themselves into a credit card trouble than same-age individuals who enter the credit card market later. So, even though the authors can’t bring themselves to say it in as many words, the CARD Act’s under-21 provision has clearly failed young Americans. Let’s take a closer look at their findings.

Younger Borrowers Are Less Likely to Pay Late and to Default

As the authors say, access to credit at an early age can have two opposite effects on default behavior. On the one hand, someone who obtains a credit card early in life has more time to accumulate debt and is therefore more likely to get behind on her payments. On the other hand, an early entrant has more time to learn how to manage her credit and can thus become a lower-risk debtor, compared to people of similar age who get their credit cards later in life. So what do we see in real life? Here is what the three economists have to say:

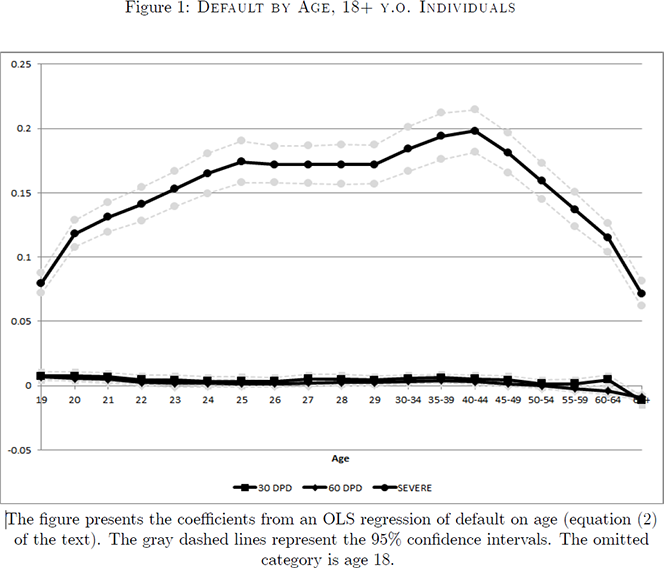

We first study whether young credit card holders are more likely than older credit card holders to experience credit card delinquency. Using data from the period prior to the Act, we find that individuals under the age of 21 are substantially less likely to experience serious delinquency (90 days past due and longer). In general, the incidence of serious delinquency has an inverse U-shaped relation with age. In particular, an individual aged 40 to 44 is 12 percentage points more likely to experience a serious delinquency than an individual aged 19. These differences are economically large considering that the share of serious delinquency in the population is less than 7 percent.

Now that we know that the youngsters are more likely to pay their credit card bills on time, we should also expect them to suffer from lower default rates. And sure enough, that is precisely what the paper finds:

Young Borrowers Are Good Borrowers

Then the CARD-Act-as-a-quasi-natural-experiment comes into play and this is where it all gets really interesting. If you segment the under-21 group based on individual preferences for getting a credit card at an early age, you can evaluate how well the early adopters are doing in comparison with the abstainers. And here is what the authors have found:

Using the passage of the Act to identify the selection effect, we find that individuals who would have chosen to enter the credit card market early in the absence of the Act are less likely to experience serious delinquency or default than the individuals who enter the credit card market later. Furthermore, these individuals are more likely to be homeowners early in life. We interpret these results as indicating that some young individuals choose to enter the credit card market to establish a credit record and thus facilitate the transition to homeownership. Our findings contrast with the view that young individuals get credit cards early primarily as a response to aggressive advertising to this demographic group.

And just in case you’ve somehow missed the point, the authors give it another try:

We find that, conditional on the length of the credit history, individuals who enter the credit card market early have a lower probability of experiencing serious delinquency later in life. In summary, we find no compelling evidence that young borrowers are bad borrowers.

There it is. Again, the three economists don’t say it in as many words, but the inescapable conclusion is that the CARD Act’s under-21 provision is doing a lot of harm to young borrowers, even as it is producing no discernible benefit.

The Takeaway

So the Richmond Fed economists are making quantitatively a point, which I’ve often argued impressionistically: that college kids are perfectly capable of managing credit cards in a responsible way and should be given the opportunity to do so. Moreover, at some point they do have to start learning how to manage credit and, as the paper in question clearly shows, the earlier that process begins, the better. Furthermore, the CARD Act’s other provisions ensure that, when a college kid does decide to open up a credit card account, she is as well protected from abuse, as makes sense.

Encouragingly, the Richmond Fed paper shows that youngsters understand perfectly well what a credit card is: a tool for making payments in a convenient way whose use — and misuse — is reflected in the cardholder’s credit history. And as the authors say, to many a youngster credit building, through its effect on eligibility for a home mortgage, is the biggest benefit a credit card has to offer. Well, I, for one, see no reason why this opportunity should be denied to them, do you?

Image credit: Flickr / StockMonkeys.com.