Payday Lending Wells Fargo Style

The New York Times’ Jessica Silver-Greenberg points me to a new report issued by the Center for Responsible Lending (CRL), which looks into an interesting development — a few large banks, including Wells Fargo and U.S. Bank, have begun offering payday loans directly to customers through their checking accounts. The lenders have chosen an interesting moment to enter the field — payday lending is facing ever closer regulatory scrutiny and is, in fact, banned in 15 states. Moreover, as Silver-Greenberg notes in another piece for The Times, even fellow big bank JPMorgan Chase has turned against payday lenders by promising to help customers to halt withdrawals and limit penalty fees.

Now, the six banks identified to offer the service are not calling it payday loan, though the report shows that that is precisely what they offer. Evidently, the lenders have decided that they need the extra revenue so badly that the risk of attracting the wrath of regulators and the general public is worth taking. And it’s not as if Wells Fargo hasn’t suffered a consumer backlash over service fees in the recent past. Many readers will recall the huge uproar caused by the debit card fees with which Wells and other banks were experimenting in late 2011, forcing the lenders to eventually abandon the idea. And yet, those debit interchange losses do need to be offset, somehow. Let’s take a look at the latest effort to do so.

Payday Lending by Another Name

CRL’s report tells us that six banks in the U.S. are currently making payday loans: Wells Fargo Bank, U.S. Bank, Regions Bank, Fifth Third Bank, Bank of Oklahoma and its affiliate banks, and Guaranty Bank. The lenders have come up with different names for the service, for example Wells Fargo is calling its offering “Direct Deposit Advance” and U.S. Bank calls its service “Checking Account Advance”. And yet, these advances work as payday loans, and are just as addictive, as the report explains:

Bank payday loans are structured in the same way as other payday loans. The bank deposits the loan amount directly into the customer’s account and then repays itself the loan amount, plus a very high fee, directly from the customer’s next incoming direct deposit of wages or public benefits. If the customer’s direct deposits are not sufficient to repay the loan, the bank typically repays itself anyway within 35 days, even if the repayment overdraws the consumer’s account, triggering high fees for this and subsequent overdraft transactions.

The fundamental structure of payday loans — a short loan term and a balloon repayment — coupled with a lack of traditional underwriting makes repeat loans highly likely. Borrowers already struggling with regular expenses or facing an emergency expense with minimal savings are typically unable to repay the entire lump-sum loan and fees and meet ongoing expenses until their next payday. Consequently, though the payday loan itself may be repaid because the lender puts itself first in line before the borrower’s other debts or expenses, the borrower must take out another loan before the end of the pay period, becoming trapped in a cycle of repeat loans.

So it is easy to see the attraction some lenders may feel toward payday loans, however unpleasant the borrowers’ position may be.

Payday Lending by the Numbers

Here are the report’s key findings:

- The annual percentage rate (APR) of bank payday loans ranges from 225 percent to 300 percent. The cost of bank payday loans ranges from $7.50 to $10 per $100 borrowed and the average term is 12 days, which means that the bank repays itself from the borrower’s next direct deposit an average of 12 days after the credit was extended. This cost and loan term translates to an annual percentage rate ranging from 225 percent to 300 percent.

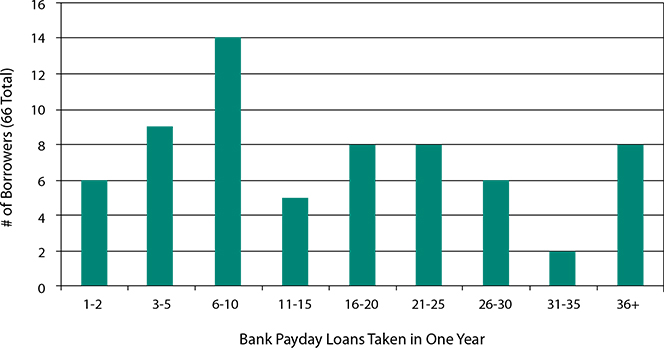

- In 2011, the median bank payday borrower took out 13.5 loans. However, as over a third of borrowers took out more than 20 loans in 2011, the mean number of loans per borrower in that year was 19. A typical borrower had one or more of her bank payday loans outstanding at some point during six calendar months during the year. Here is a graph showing the full distribution:

- Bank payday borrowers are two times more likely to incur overdraft fees than bank customers as a whole. The CRL researchers have found that nearly two-thirds of bank payday borrowers incur overdraft fees.

- More than a quarter of all bank payday borrowers are Social Security recipients. The researchers have calculated that at the end of a two-month period during which a Social Security Recipient has spent 47 of 61 days in payday loan debt, the borrower is again left with a negative balance, in an immediate crisis and in need of another loan.

And it doesn’t help that, almost by definition, the typical payday loan borrower is more prone to making bad financial decisions than the average consumer.

The Takeaway

The payday loan industry has been thriving in the U.S. and, as NYT’s Silver-Greenberg reminds us, many lenders have been moving online, at least in part as an attempt to circumvent existing regulations. From 2006 to 2011, she tells us, the volume of online payday loans grew by more than 120 percent — from $5.8 billion to $13 billion. Moreover, online-only, new-age payday loan alternatives like BillFloat are better than the more traditional options.

Yet, in case anyone needed convincing, CRL’s report illustrates that payday loans are not exactly a consumer-friendly service and a Wells Fargo spokeswoman has admitted as much to Silver-Greenberg, adding that the service “is an important option for our customers and is designed as an emergency option”. Still, a 300 percent interest rate is grossly excessive.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.