Why Square’s Sky-high Valuation, Unlike LinkedIn’s or Skype’s, Makes Sense

A month ago I read an article in the Economist about the latest crop of mind-blowingly high valuations of high-tech companies. The article began with a throwback to the years immediately following the previous era of insanely high valuations of today’s favorites’ predecessors a decade ago when bumper stickers read: “Please God, just one more bubble.”

The author then proceeded to declare that that wish had now been granted, however belatedly. It is hard to argue otherwise. Microsoft recently bought Skype for $8.5 billion – ten times the internet voice call provider’s 2010 sales and 400 times its operating income. LinkedIn was hoping for a valuation of $3.3 billion at its Initial Public Offering (IPO) in May. Instead, at the end of the first day of trading, the social networks for professionals was valued at close to $9 billion, 37 times the company’s 2010 net revenue and about 2,650 times its net profit.

So when earlier this week we learned that Square had raised $100 million on a valuation of $1.6 billion, surely we got yet another confirmation, in case we needed it, that the latest high-tech craze has arrived, right? Well, no we did not. While I agree that a high-tech bubble is being inflated, I would argue that Square is not a part of it. Let me explain.

Square Is Different

I know, you’ve heard that before. Nevertheless, it is true. After all, remember that out of the wreckage of the dot-com era emerged companies like Amazon and eBay, which are still thriving today. The current incarnation of the dot-com madness will be no different and will produce real companies which will be successful long after the bubble has burst. Square will be among them.

See, unlike LinkedIn and Skype, Square shows you exactly how it will make real money. Yes, the company is currently in the red, as the NYT points out, but that is because it is at present focused exclusively on growth, not because it does not yet know how to make money. That is precisely the strategy employed by Amazon a decade ago and it paid off handsomely for Jeff Bezos and company.

Square Is the Mobile PayPal

Think of Square as the mobile PayPal, which it is, although PayPal has its own m-payment offerings. The doubts about Square focus on the viability of a business model that is built around enabling consumers to accept credit card payments. The start-up does make it easier for some types of small businesses to accept cards, but it is true that its core users are consumers.

So how can it be successful with a base of users who for the most part will take cards a few times a year, the critics would ask. Well, PayPal has already showed how this can be achieved and it is a numbers game. eBay’s subsidiary currently manages more than 87 million active accounts worldwide. Its revenue grew 23 percent to almost a billion in the first quarter of this year. PayPal is now one of the biggest payment processing companies in the world.

So Square is not in an uncharted territory. All it has to do is copy what PayPal has done a decade ago. And they are doing precisely that, with former PayPal Executive VP Keith Rabois at the helm as COO.

The Takeaway

We’ve done the numbers on how profitable Square is before and you can review our calculations here, here and here. Our estimate showed that “for every $1 million processed, Square gets about $13,000 – $14,000 in revenues,” but that was before the start-up dropped the per-transaction fee from its discount rate, which will reduce this total by at least a couple of thousand dollars. Still, Square probably gets about a cent for every dollar it processes.

We’ve done the numbers on how profitable Square is before and you can review our calculations here, here and here. Our estimate showed that “for every $1 million processed, Square gets about $13,000 – $14,000 in revenues,” but that was before the start-up dropped the per-transaction fee from its discount rate, which will reduce this total by at least a couple of thousand dollars. Still, Square probably gets about a cent for every dollar it processes.

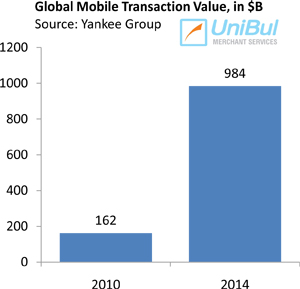

This is a great rate, although to an industry outsider it could look way too modest. Then again, it is a numbers game. Various forecasts give different numbers for the expected growth of mobile payments in the coming years. All of them, however, point to an exponential growth. The Yankee Group, for example predicts that globally by 2015 the value of mobile payments transactions will reach $984 billion in 2014, up from $162 billion in 2010. If Square can grab just one percent of this market, it would be processing more than $10 billion by 2015. Now the fee the start-up charges looks much less modest, doesn’t it?

Image credit: Squareup.com.