Prepaid Cards: Short-Lived, Underused and Increasingly Popular

That is the gist of a recent study by three Philadelphia Fed researchers. Prepaid cards still make up a relatively small share of the consumer payments total in the U.S., they remind us, but have been growing much faster than the other two major payment card types — credit and debit — and have now become too big to ignore. The researchers have focused on one segment of the prepaid card market — open-loop reloadable cards, which accounts for about 30 percent of the total. Open-loop are prepaid cards that bear the logo of one of the major payment card networks and can be used for payment at any merchant that accepts that card brand.

The researchers have taken a close look at consumers’ usage patterns, such as longevity, the number and value of purchases, ATM withdrawals, the mix of retailers where purchases occur, bill payments, and funds loaded onto the cards. They have also examined the make-up of the cardholder fees collected by the issuers for each of the prepaid card categories. And this is where the significance of direct deposits jumped out at me: it turns out that the usage of this feature makes prepaid cards many times more profitable for issuers than otherwise. Let’s take a closer look at the study’s findings.

The Average Prepaid Card Lasts for 6 Months

The researchers compare prepaid cards to their most closely-related product and find that:

Prepaid cards offer much of the functionality of checking accounts, but that does not mean the underlying economics are the same. A typical prepaid card in the data is active for six months or less, a small fraction of the longevity seen with consumer checking accounts. As a result, account acquisition strategy and the recovery of fixed and variable costs are likely different than for checking accounts.

Then the economists go on to explain that:

[A]ny fixed costs associated with establishing a reloadable prepaid card used by a consumer must be recovered over a time span that is only 5 to 15 percent that of a typical checking account.

Of course, another option would be to try to increase the lifespan of prepaid cards and that is precisely what the use of the direct deposit feature has achieved. More on that in a minute.

Most Prepaid Cards Are Rarely Used

We learn that:

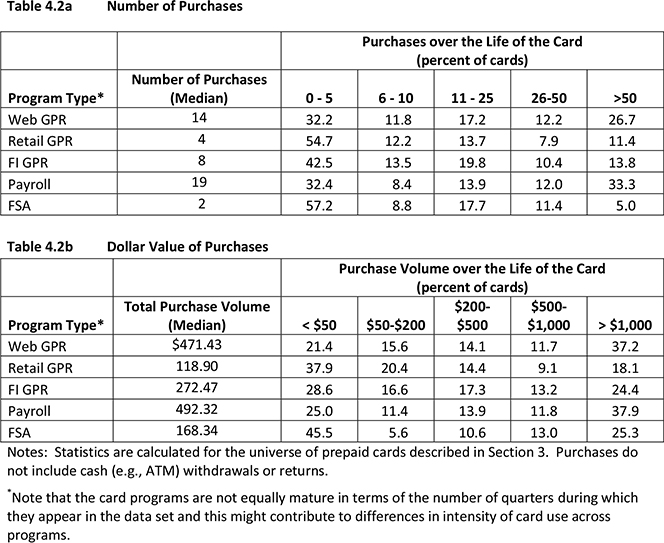

A typical (median) prepaid card in these programs is not used for a large number of purchases. This statistic is better explored by examining the shares of prepaid cards allocated into different categories of purchase transaction frequency ranging from zero to more than 50 over the life of the card. This breakdown illustrates a bimodal pattern in the usage of prepaid cards — the largest shares of cards in most program categories are hardly used (five or fewer purchase transactions) or are used quite intensively (51 or more purchase transactions).

Here is the full breakdown by number and dollar value of purchases:

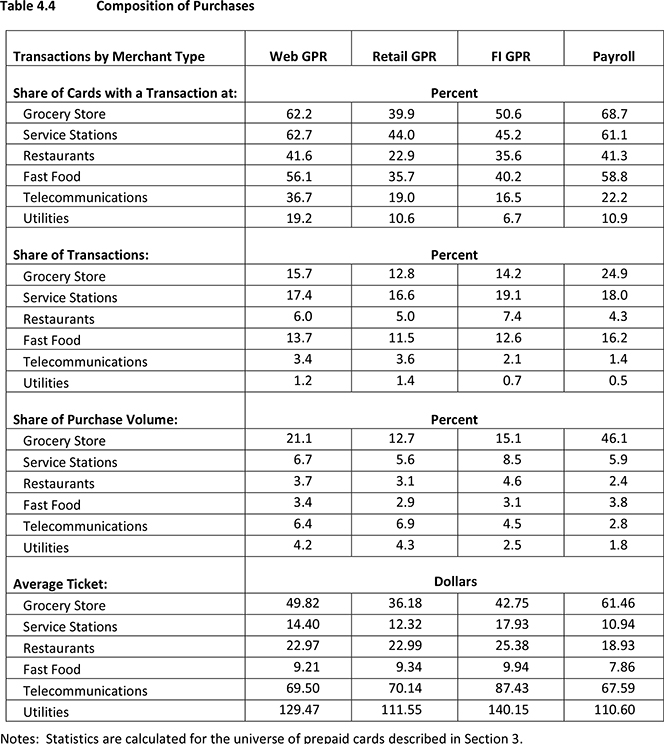

Purchases at three types of stores (grocery, service stations, and fast food) account for about half of all purchase transactions and about a third of the transaction value, we learn. Here is the full breakdown:

The Direct Deposit Advantage

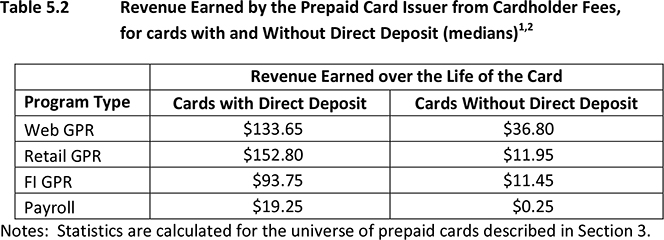

Now let’s look at the statistics, which I think are the most interesting ones in the paper. Here is what we learn:

An extremely important distinction for the prepaid cards we study is the presence (or lack thereof) of repeated value loads that appear to reflect direct deposit. While uncommon, general purpose prepaid cards with such patterns remain active at least twice as long (or longer) and have 10 times or more purchase and other activity than other cards in the same program category. These cards also generate at least four times more revenue for the prepaid card issuer. Average monthly cardholder costs are about twice as high, because these cards are used more intensively; on a per transaction basis, cardholder costs are lower.

And here is the breakdown of the issuers’ revenues from cards with and without direct deposits:

Small wonder than that American Express, Chase and others are now offering prepaid cards with no or very low monthly and other fees. If the issuers can convince consumers to get their paychecks direct-deposited into their prepaid accounts, they will be more than well compensated for the concession.

The Takeaway

The Philadelphia Fed researchers’ findings clearly indicate that consumers view prepaid cards as a payment product that is distinctly different from debit and credit cards. There is plenty of information that is still needed for a more complete picture of consumers’ usage patterns to emerge, but we now know that the direct deposit feature is an extremely important factor in determining how long a prepaid card will remain active and how often it will be used.

Image credit: Creditcardcity.com.

Good post. Prepaid cards truly are coming of age and there is a lot of demand for them to be met.