More than Half of U.S. Student Loans Are Deferred

It was TransUnion’s turn this morning to tell us just how bad the student loan situation in the U.S. has become. Only last week, FICO—the provider of the most widely used consumer credit scores in the country—told us that a quarter of all student loans in the U.S. were past due by 90 days or more. Now one of the nation’s three biggest credit reporting agencies is reporting that more than half of all student loans are in deferment. There are some differences between the two studies, as should be expected, but the trend is clear.

TransUnion’s study is also interesting in another respect. Unlike the FICO report, the credit reporting agency’s study breaks down the data by student loan origination type. It turns out that during the recession and the ongoing recovery, federal loans have accounted for practically all of the growth in the overall balances. Moreover, whereas the federal loans’ delinquency rate has risen substantially, the corresponding rate of private loans has actually fallen. This discrepancy is not exactly surprising, considering that the federal student loan programs are designed with the explicit goal of giving everyone a chance to get a college degree and so the government doesn’t make loan decisions based on the borrowers’ ability to repay the debt. As long as that remains the policy, I can’t see how the current trend could be reversed.

More than Half of U.S. Student Loans Are Deferred

TransUnion has found that 51 percent of all student loan accounts in the U.S. are in deferred status, where the repayment of the principal and interest of the loan is postponed, sometimes for up to three years. Measured by volume, deferred loans now account for 43.5 percent of total balances.

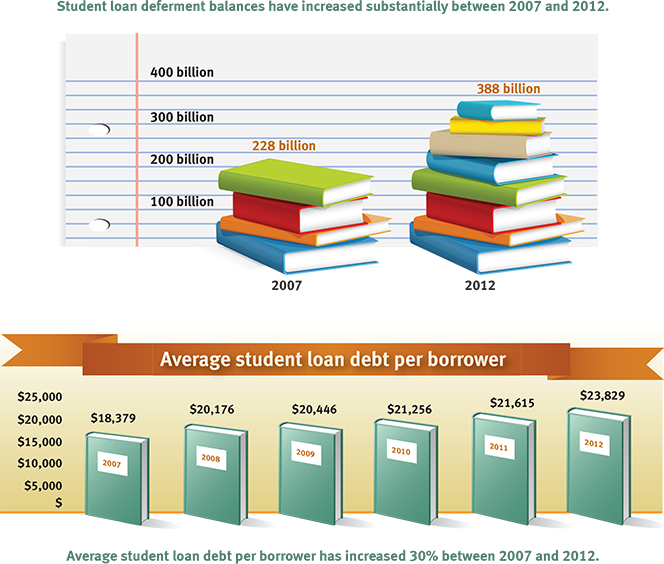

The recession has clearly exacerbated the problem. Between 2007 and 2012, total balances of deferred loans have spiked by 70 percent—from $228 billion to $388 billion—and, as the report’s authors note, rising unemployment has had a lot to do with it. The study cites an analysis of government data, conducted for The Associated Press, according to which more than half of all U.S. college graduates under the age of 25 are either unemployed or underemployed—the highest rate in 11 years. However, as Ezra Becker, a TransUnion vice president, notes, the problem is that you can only defer payment on a student loan for so long:

It is especially noteworthy that more than half the student loans in our study were in deferment, and with unemployment rates remaining high, particularly among recent graduates, the repayment of these loans remains a concern. Students can defer their loans for only a certain period, often up to three years. After that, these students can find themselves in a difficult position financially.

That is putting it mildly, considering that student loans cannot even be discharged in bankruptcy.

Student Loan Balances up by 75% since 2007

TransUnion tells us that between 2007 and 2012 student loan balances rose by 75 percent, with the average student loan balance per borrower increasing by 30 percent—from $18,379 to $23,829. As others have suggested before him, Becker notes that the state of the economy has influenced the decision of a higher-than-usual share of the working-age population to go back to college:

With the economy either in recession or slowly coming out of it during the study period, we had expected that student loan balances might increase as consumers frustrated with the job market went back to school to work toward a different career path. However, the rate of growth we observed was truly eye opening.

And now we come to the interesting issue of the make-up of student loan originations. In 2009, the Student Aid and Fiscal Responsibility Act (SAFRA) limited the origination of federally-funded educational loans to four providers. As already noted, this federal lending program was designed to make college education available to everyone. TransUnion tells us that student loans issued by private lenders typically go to cover the gap between loans extended by government-backed programs and the actual tuition costs. According to the study, federal loans make up 92 percent of all student loan accounts and 86 percent of overall balances. Tellingly, between 2007 and 2012, federal loan balances increased by 97 percent, while private loan balances only rose 4 percent. Clearly, the federal program is being implemented as intended.

Delinquencies Up

As it should be expected, expanding the volume of student loan balances by 75 percent during a deep recession and its messy aftermath has led to an increase in the delinquency rates. And this is the statistic that illustrates most clearly the difference in underwriting policies between the federal and private lending programs. Between 2007 and 2012, we learn, federal student loan delinquencies rose by 27 percent, whereas private loan delinquency rates actually fell by 2 percent for the period. As of March 2012, the ratio of payments late by 90 days or more was 12.31 percent for federal loans, compared to 5.33 percent for private loans. For perspective, even the much lower private-loan delinquency rate is high compared to corresponding rates for other consumer loan types. As Becker says:

It’s important to highlight that both federal and private student loan delinquency rates are higher than most other credit products such as mortgages, home equity lines of credit, credit cards and auto loans. While the focus in recent years has been on the mortgage market, lenders will need to keep an eye on student loan portfolios — and on customers who have student loan debt — as the high delinquency rates among these borrowers can spell trouble across multiple products.

Here is an infographic presenting some of TransUnion’s findings:

The Takeaway

Using a different methodology, the FICO study calculated a 25.1 percent rate for payments overdue by 90 days or more for student loans opened before October 2010, a much higher ratio than TransUnion’s. Yet, however measured, the delinquency rate is unsustainably high and clearly tells us that student loans are being extended at an ever-increasing rate to borrowers who cannot pay them back. This makes no sense to me. The federal lending programs are intended to ensure that people get a better start in life, but they all too often achieve the opposite outcome, producing a huge number of college dropouts who not only end up entering the workforce without a college degree and with few prospects for a well-paying job, but are burdened with huge amounts of student debt that cannot even be discharged in bankruptcy. How is that helping them?

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.