More on Using Alternative Data for Determining Creditworthiness

A new study by Javelin Strategy and Research, and commissioned by LexisNexis, delves into the fashionable issue of using alternative data for the purposes of establishing the creditworthiness of loan applicants. There is great need for the use of such data, the authors argue, as various factors have combined to make it increasingly difficult for lenders to determine the level of risk posed by a diverse array of borrowers. The Great Recession has taken its toll on the credit reports of otherwise responsible borrowers, sometimes pushing them outside of the traditional financial system. As a consequence, lenders need more information to help them separate genuinely risky borrowers from those whose present financial troubles are not correctly reflecting their actual creditworthiness, the report argues.

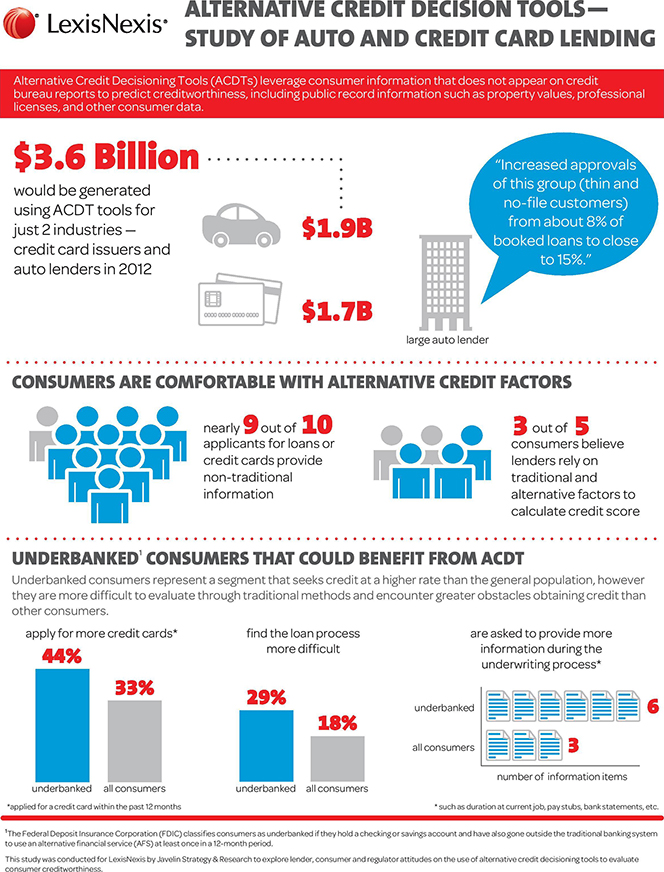

Then of course lenders have to deal with the more traditional issue of evaluating the credit risk posed by consumers with thin or no credit files. Needless to say, they find the potential of alternative sources to provide the additional data that could allow them to assess that risk more accurately at the very least worth exploring. The authors tell us that, had such alternative data been used in 2012, credit card issuers could have generated $1.7 billion in additional revenue and auto lenders — $1.9 billion in that year alone. To me the most interesting part of the report is the one dealing with one underserved consumer segment, about which we have written quite a bit on this blog: the underbanked consumers. Let’s take a look at what the authors have found.

Who Are the Underbanked?

There are several definitions of an underbanked consumer, but the report’s authors use the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) one: consumers are underbanked if they hold a checking or savings account and have also gone outside the traditional banking system to use an alternative financial service (AFS) at least once in a 12-month period. The underbanked represent 21 percent of all U.S. adults, or more than 50 million consumers.

Now, as the authors note, even as they utilize alternative financial services, the underbanked are quite active in the traditional financial system. The use of AFSs suggests that they are not having their financial needs fully met by the banks and other traditional lenders. In fact, we learn that the underbanked apply for loans and credit cards more frequently than all consumers. However, they go through a more intensive underwriting process, which, unsurprisingly, they find more difficult than consumers as a whole, and are more frequently denied credit. The underbanked demonstrate that they understand the underwriting process, the report finds, but are more likely to have a credit score that qualifies them only for sub-prime loans. Yet, their huge numbers and the interest they promise to generate attract the interest of lenders. The problem is that this group is exceptionally risky for lenders, because they are prone to high rates of default.

What Alternative Financial Services Do the Unbanked Use?

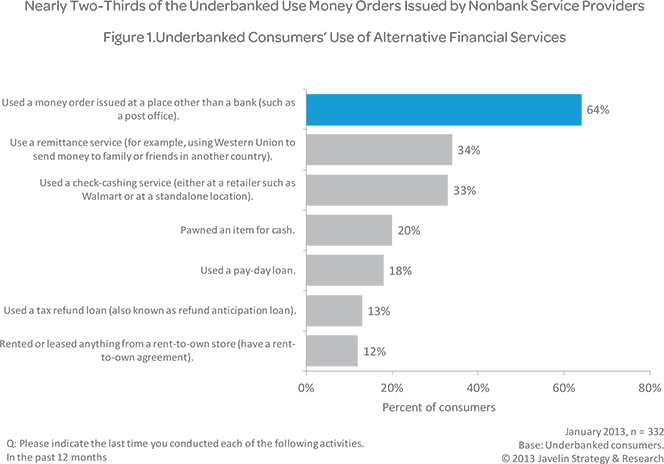

By far the most popular AFS among the underbanked — used by close to two-thirds of them — is the money order issued by a non-bank (for example, the post office). Here is the full list:

The Underbanked Actively Use Traditional Financial Services

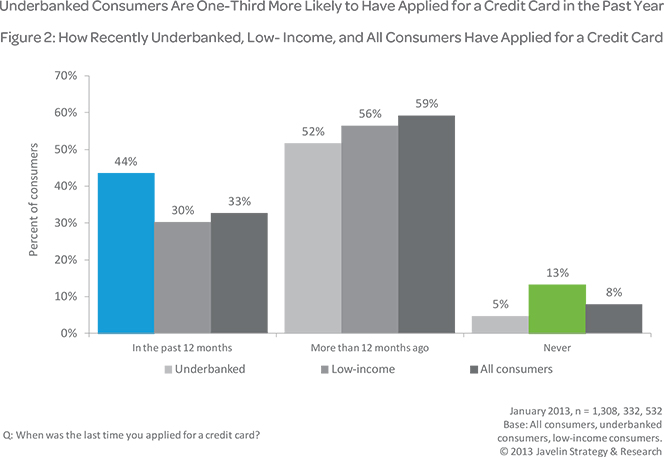

Even as they conduct some of their financial activities outside of the traditional banking system, the underbanked are actively using the traditional channels. For example, they own the same number (six) of financial products as all consumers and are more likely (44 percent vs. 33 percent) to have applied for a credit card in the past year than all consumers.

Moreover, the underbanked are the fastest growing market for traditional lenders, we learn. The authors cite a 2012 CFSI study, according to which revenue from fees and interest in the underbanked market for credit, payments, deposit, and other financial products grew by 7 percent to $78 billion from 2010 to 2011. In the same period, the volume of business conducted by the underbanked grew by 5 percent to $649 billion. So the underbanked can make for good customers, provided the lender can accurately assess the associated risk.

The Underbanked Suffer from Poor Credit History, not from the Lack of It

The underbanked, it turns out, are not typically younger than 25 and their use of traditional financial products is comparable with all consumers. So the vast majority of them have credit files that are sufficiently long for them to be scored. The trouble is that their credit scores are low. When asked, almost half of the underbanked who have viewed their credit score in the past year said they scored below 680 (46 percent, compared with 26 percent of all consumers). When asked why they believed their credit score was low, they were more likely to cite late payments (33 percent vs. 28 percent), and collection accounts (31 percent vs. 25 percent). Regardless of their credit scores, the underbanked were also more than twice as likely to say that they had made more late payments in the past six months (20 percent vs. 8 percent).

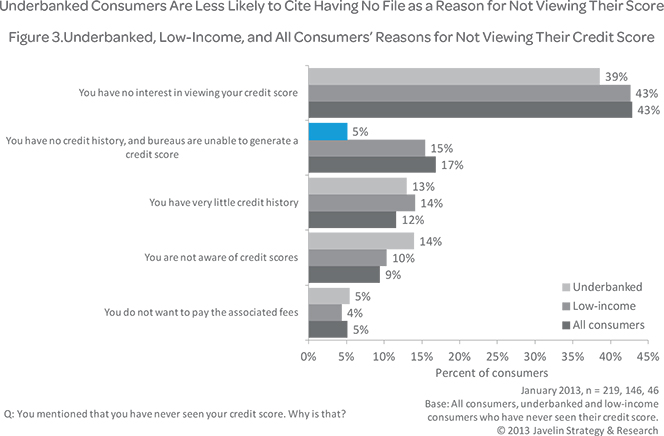

The underbanked are slightly more likely than consumers as a whole to check on their credit scores — 14 percent of underbanked consumers said they had never seen their credit score, compared with 17 percent of all consumers.

Difficult Underwriting Process

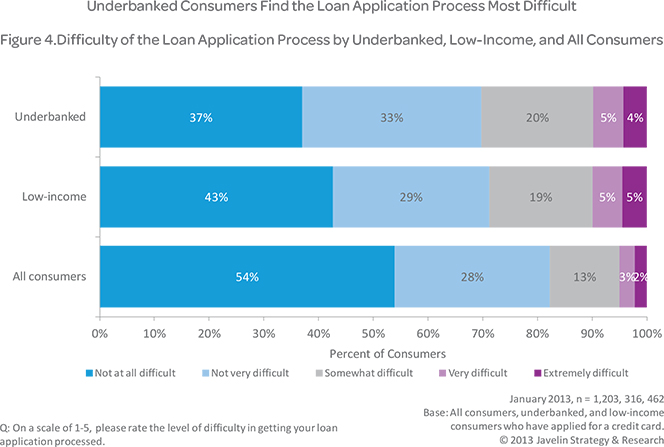

As it should be expected, given their high-risk classification, the underbanked face a more intensive underwriting process than consumers as a whole. They are more frequently asked for a variety of information and documents, such as employment status (71 percent vs. 63 percent), duration at their current job (53 percent vs. 41 percent), pay stubs (32 percent vs. 19 percent), and bank statements (23 percent vs. 12 percent). Unsurprisingly then, the underbanked who had applied for either credit cards or auto loans found the application process more difficult (29 percent rated the process at least somewhat difficult vs. 18 percent of all consumers).

The Takeaway

Having taken a close look at the underbanked’s relationship with traditional and non-traditional financial products, the authors suggest that alternative data “may be able to reduce the burden to both loan officers and underbanked consumers by providing additional information on behalf of the consumer”. Well, whereas that may be the case for younger consumers, with thin credit files, I just don’t see how alternative data may help with the underbanked who, as we saw, tend to be older than 25 and have had the time to build up their credit files. The problem, once again, is not that there are not enough data for this consumer segment, but that the data that are available clearly show that the underbanked are too high of a risk for traditional lenders.

Finally, here is a nice infographic produced by the report’s authors:

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.

I agree that alternative data might be the necessary tool in tapping into the underbanked market. However, I contest your generalizations of who are the underbanked. For example, 28% of underbanked consumers earn more than $75,000 a year. Additionally, 9.5 million members of Generation Y are considered underbanked, not just because of late payments and collection accounts. This generation grew up during financial turmoil and is adverse to credit/debt. It?ÇÖs not that they don?ÇÖt make their payments on time; it?ÇÖs that they don?ÇÖt have any payments to make. Yet there is certainly alternative data available on these consumers, giving financial institutions an opportunity to reach new clientele that in actuality, are not as risky as this article suggests. To be fair, the population of poor credit consumers has grown during the recession and also represents a potential market as they return to financial health.