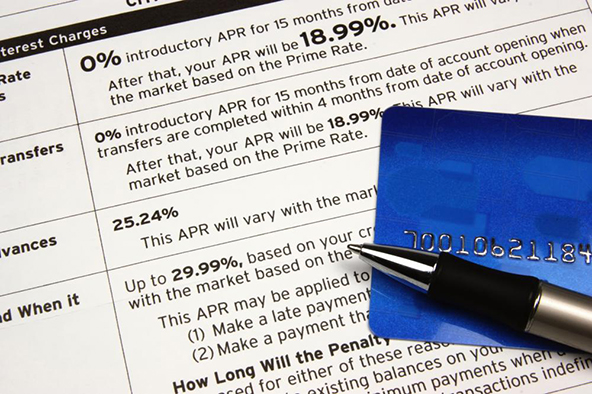

Do You Understand Your Credit Card Agreement?

The government is once again attempting to simplify credit card agreements, various news outlets are reporting this morning. This time the agency in charge of the project is the recently founded U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB).

You may remember that not too long ago, Congress itself passed the CARD Act, which was intended to protect consumers against unfair practices employed by credit card companies. Prominent among the act’s provisions were mandates for clear and easy-to-understand disclosures of the terms of agreement, which were supposed to eliminate confusion among consumers. Now the CFPB is trying to achieve exactly the same objective all over again.

CFPB’s Goal: Short, Simple Credit Card Agreements

Bloomberg has a reference to a “prototype” of CFPB’s vision for the ideal credit card agreement, but the link is broken and I have not been able to locate the document on CFPB’s website. So I’m relying on Bloomberg’s description:

The standardized, two-page card agreement outlines prices, risks and terms that are shorter and more concise than conventional agreements, augmented by an online glossary to aid consumers on such items as billing disputes, privacy, rights, interest-rate calculations and the consequences of late payments.

What this new agreement template is expected to achieve is summarized by Raj Date, a special adviser to the Secretary of the Treasury, as quoted in Bloomberg’s piece:

Credit cards can be complicated. With a short, simple, easy-to-understand credit card agreement, consumers can clearly see the terms of the deal and make decisions that are right for them.

Well, as I said, the CARD Act was supposed to achieve precisely that.

CARD Act on Credit Card Agreements

Let’s take a look the part of the act dealing with credit card agreements:

Plain Sight / Plain Language Disclosures: Credit card contract terms will be disclosed in language that consumers can see and understand so they can avoid unnecessary costs and manage their finances.

- Plain Language in Plain Sight: Creditors will give consumers clear disclosures of account terms before consumers open an account, and clear statements of the activity on consumers’ accounts afterwards. For example, pre-opening disclosures will highlight fees consumers may be charged and periodic statements will conspicuously display fees they have paid in the current month and the year to date as well as the reasons for those fees. These disclosures will help consumers make informed choices about using the right financial products and managing their own financial needs. Model disclosures will be updated regularly based on reviews of the market, empirical research, and testing with consumers to ensure that disclosures remain clear, useful, and relevant.

- Real Information about the Financial Consequences of Decisions: Issuers will be required to show the consequences to consumers of their credit decisions.

- Issuers will need to display on periodic statements how long it would take to pay off the existing balance and the total interest cost if the consumer paid only the minimum due.

- Issuers will also have to display the payment amount and total interest cost to pay off the existing balance in 36 months.

Additionally, the act required issuers to post credit card agreements on the internet, so that both consumers and regulators would have an easy access to them. So what was the effect of these changes? Let’s look at CFPB’s own assessment.

CFPB on CARD Act’s Effect on Credit Card Agreements

Here is how the CFPB assessed the Act’s success at clarifying credit card terms and conditions for consumers:

- 80 percent of cardholders have noticed that their payments are now due on the same day of each month

- 77 percent have noticed that the monthly statements contain a warning about the cost of making a late payment

- 70 percent of cardholders have noticed that monthly statements now contain information about the consequences of making only minimum payments

- 48 percent of consumers recall that their bill now tells them how much to pay each month in order to pay off the balance within three years

- 31 percent of cardholders who recall seeing the new information on their statement report that this information has caused them either to increase the payments they make or to reduce their use of credit.

- Of the cardholders who have noticed at least one of the changes in their monthly billing statements, 60 percent say that their monthly statements are easier to read and understand than they were a year ago. Additionally, 60 percent say that the terms of their credit card are clearer than they used to be.

- At the same time, 32 percent of those who carry a balance from month to month say they do not know how much interest they paid on their primary credit card last year.

This sounds to me like a fairly positive evaluation. Fully 60 percent of consumers already find the agreements both easier to read and more clear. Considering that a substantial number of consumers will not have read their agreements to begin with, two of Mr. Date’s objectives seem to have been achieved quite successfully by the CARD Act.

What about helping consumers understand the meaning of terms like “billing disputes, privacy, rights, interest-rate calculations and the consequences of late payments?” Well, isn’t it obvious what a billing dispute is? I mean, what is there to be clarified? And isn’t it equally obvious that payments should be made on time and that the consequences of not doing it would be unpleasant? Not to mention that these consequences are already prominently disclosed in each agreement in the form of a late payment fee and that the CFPB’s own assessment states that 77 percent of consumers are aware of them.

Regarding privacy and rights, these terms need no explanation, but a disclosure and have already been heavily regulated in the CARD Act and other legislations. Finally, interest rate calculations can indeed be difficult to understand for everyone and I don’t think that any amount of explanation can change that fact. However, that does not mean that consumers are not protected against high interest rates. For example, the CARD Act banned retroactive interest rate hikes, required a clear disclosure of any promotional rates, gave consumers the right to close an account, with no negative consequences, if they did not agree with a proposed rate increase, put a stop to the practice of “universal default,” etc.

The Takeaway

The way I see it, what the CFPB is attempting to do with credit card agreements has already been achieved quite successfully by the CARD Act, even by the CFPB’s own assessment. I have no idea why the agency has taken up this task, but I think that it is wasting government resources.

Image credit: Wisegeek.com.

I’m not sure you have this right. You are confusing monthly statements with the agreement. Specifically, when you say “Fully 60 percent of consumers already find the agreements both easier to read and more clear” you are comparing Apples to Oranges. The survey was talking about changes to the monthly bill, not to the agreement.

The link worked for me, maybe you should try again and comment on the actual situation.