Prepaid Cards Are a Better Alternative to Paper Paychecks

A couple of weeks ago a widely circulated New York Times piece told horror stories about the evils of prepaid cards replacing paper paychecks for an increasing number of American workers. Using such cards involves paying fees, we were informed, which can “take such a big bite out of paychecks that some employees end up making less than the minimum wage once the charges are taken into account”. Sure enough, a couple of days after the story was published, the NYT reported that Eric Schneiderman — New York’s Attorney General — was investigating the issue and had sent letters “seeking information” to about 20 private employers, including McDonald’s, Walgreen and Wal-Mart.

Well, what Schneiderman could also do is to read a report just published by the Association of Government Accountants (AGA), which looks into the very issue he is investigating. What New York’s AG would learn if he chose to read the AGA report is that recipients of government benefits (for example, unemployment compensation, social security, supplemental security income, etc.) saved hundreds of millions of dollars in 2011 alone by using prepaid cards in place of check-cashing services. Check-cashing costs, it turns out, are far greater than prepaid card-related fees. Let’s take a closer look at the AGA report.

Why Governments Use Prepaid Cards

There are several major reasons why various state and federal government agencies are switching to prepaid cards. The primary reason, according to the AGA report, is that prepaid card programs saved the government money, a lot of money. To begin with, such programs can be implemented at no or low cost to government agencies. Moreover, the AGA tells us, the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Management Service (FMS) “is projected to save an estimated $1 billion over the next 10 years by moving Social Security, Supplemental Security Income and other paper check payments to prepaid cards”.

But disbursing benefits through prepaid cards offers other advantages as well:

Other major reasons that governments switched to prepaid debit cards included better cash access and improved security for recipients of government payments. Government agencies saw the cards as a way to increase the options available to the unbanked for accessing funds. With a prepaid debit card, government cardholders have the same access that all other cardholders have to automated teller machines (ATMs) and retailers that offer cash back with purchases. Cardholders have the flexibility to access some or all of their funds at one time and, even though their card is not tied to an individual bank account, they have the option of going into a bank to obtain cash from their card. Cardholders can make purchases at any retailer that accepts the brand displayed on their card (i.e., Visa or MasterCard), and can shop and pay bills online or by phone, thereby taking major steps into the financial mainstream.

Moreover, prepaid cards are more secure than checks, not least because recipients do not need to carry large amounts of cash after cashing a check, but also because the cards don’t have to be mailed out each month, as check do.

Now let’s move on to the cost of using prepaid cards.

Prepaid Cards Save You Millions

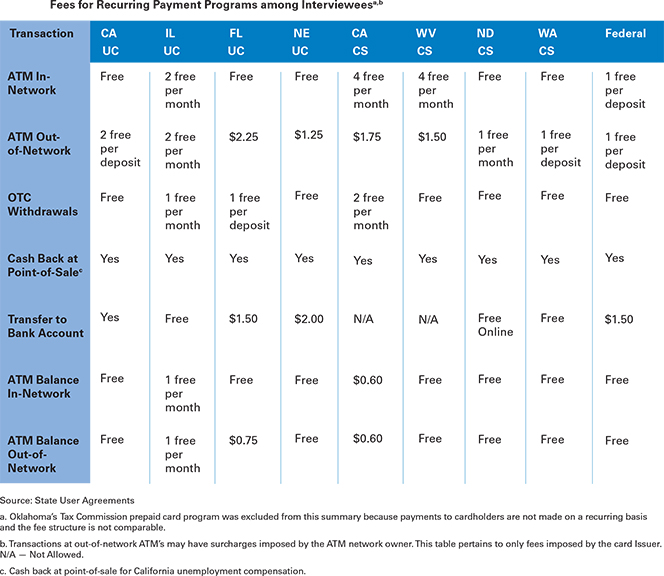

The table below summarizes the fees that holders of various government-issued prepaid cards may incur.

According to a 2011 Federal Reserve report cited by the AGA, in that year the 15 issuers for government prepaid card programs reported to have received $120 million in cardholder fees, an average of $6.33 per card, or 0.3 percent of the dollars disbursed through government payment prepaid cards annually. At $59 million, ATM fees made up the largest portion of the total cardholder fees.

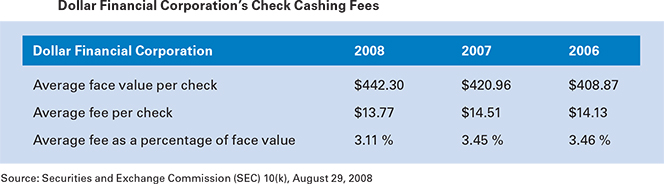

Regulations regarding check-cashing fees vary by state, but the researchers tell us that the average costs are “comparable” to those presented in the table below.

Additionally, we learn that in California, for example, the fee is limited to three percent of the check amount for payroll or government checks, provided the individual presents the check and identification. In Illinois, the check cashing fee cannot exceed 1.4 percent of face value plus a service charge of $1 on all checks equaling $100 or less, and 2.25 percent on checks over $100. Check-cashing fees in Florida are in the range of one to three percent of the check’s face value.

When applied to the dollar amount of the government payments disbursed on prepaid cards, the difference in fees for each service is quite significant. For example, a Federal Reserve report cited by the AGA states that in 2011 26 states reported disbursing $39 billion in unemployment compensation benefits, 35 percent (or $14.43 billion) of which was expended using prepaid cards. If, as we just saw, check-cashing fees typically range from one to three percent of the check amount, while the average prepaid cardholder’s fees was only 0.3 percent, recipients who received unemployment compensation benefits through prepaid cards have collectively saved between $100 million and $389 million in fees per year in the 26 states covered by the report.

The Takeaway

So there are very good reasons to believe that employers who have elected to deposit their employees’ paychecks into prepaid card accounts are onto something and the various prepaid card-related fees bandied about in the NYT piece should all be put in perspective. There is no question that some cardholders would be paying the out-of-network ATM charges or paper statement fees the NYT mentions, but as we have seen, on average prepaid cards beat paper checks hands down.

Moreover, there is evidence that the savings keep growing as employees get used to their cards. The Federal Reserve report cited in the AGA study tells us that “cardholders have become adept at avoiding fees”, meaning that over time they learn which ATMs and transactions are free of charge. So I really don’t see what is there for Schneiderman to investigate — it seems to me that replacing paper paychecks with prepaid cards is simply the sensible thing to do.

Image credit: Flickr / Thomas Hawk.

I think you’re comparing apples to oranges.

Yes, prepaid card programs that have low fees, such as those being used by governments for various benefits programs, have a lower recipient cost for the recipients who are unbanked/underbanked and are comparable in recipient cost to payment by check for the recipients who are adequately banked. And the prepaid card programs that are being heavily marketed to employers and that have high fees have roughly equivalent recipient cost for the recipients who are unbanked/underbanked (as compared to check cashing, etc.) But these high fees prepaid card programs have much higher recipient cost for recipients who are adequately banked and who can deposit paychecks at zero incremental cost.

Even the low fees prepaid cards provided by various government benefits programs have the disadvantage, I would think, for the adequately banked recipients in that they would find it hard to make payments to entities that want to receive a check rather than process a credit card or debit card transaction. For example, paying rent to a small landlord. There are some prepaid products like Bluebird that would allow recipients to write checks against the received amount.