Square Goes Online, Takes on Amazon, eBay

It was bound to happen and now it has. Square, the company which pioneered the smart phone-based credit card acceptance, has just launched an online marketplace, called Square Market. In a direct challenge to Amazon and eBay, Market is designed to enable small businesses which lack the resources or expertise to set up and maintain a dedicated e-commerce website to sell their products and services on Square’s new, sleek e-commerce platform. And yes, as everything Square does, Market is very sleek.

Apart from its pleasing design, Market does have a couple of big things going for it. Firstly, Square has already cultivated relationships with millions of very small sellers — the vast majority of them couldn’t really be called merchants — which are precisely the types of users Market is designed to serve. Eager to explore that advantage, Square has made it incredibly easy for users of its offline service — Square Register — to start selling online and I have little doubt that many will at the very least give it a try. Secondly, Square is exploiting its close relationship with Twitter (CEO Jack Dorsey is Twitter’s chairman) to enable Market users to post items directly to Twitter for their followers to discover, purchase and / or share. And I expect it to succeed. So let’s take a look at Square’s latest.

How Market Works

Market is designed as an add-in to Register — Square’s offline payment processing service, which allows sellers to swipe their customers’ cards for payment, as well as to create a customizable library of the items they sell, complete with their names, photos, order modifiers and prices. Additionally, Register comes with features like sales reporting, transaction history, business analytics, staff management, rewards program and others which, up until it was first released were only present in expensive point-of-sale (POS) systems, which only large merchants could afford. Moreover, it is all wrapped up in a neat interface.

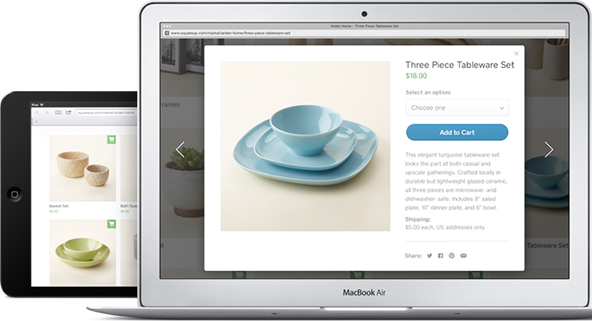

With Market, Square offers its Register users the choice of selling their merchandise online. All a user has to do is select the option of selling online within the Register app and her products are immediately posted on her Square online store. In keeping with the processor’s overarching theme of stripping off all that is unnecessary, these stores contain only the bare minimum: the business’ name and address, a short profile and a large photo giving you a general idea of the things the store sells and then smaller pictures, descriptions and prices of the individual items, as well as small buttons to buy them, which are placed within the products’ photos (as can be seen here, for example). That is all.

Unlike eBay, Square doesn’t charge listing fees or in fact anything other than its regular payment processing fee of 2.75 percent of each transaction’s amount. WePay is another processor which utilizes the same business model, but, at 4.9 percent plus 30?ó, its payment processing fee is much higher than Square’s.

Using Twitter

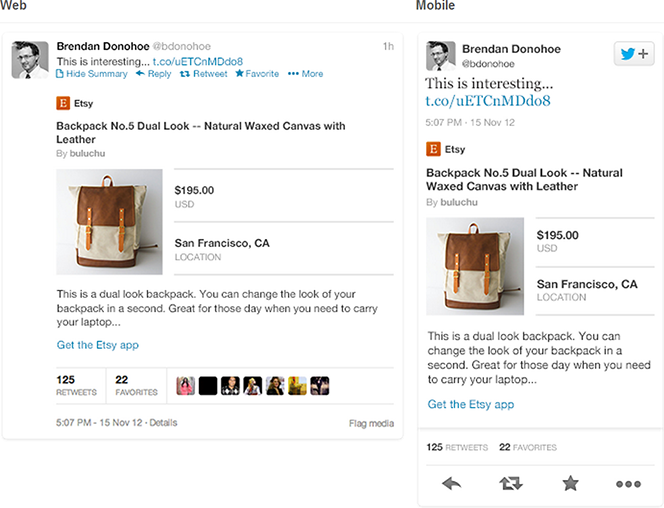

In the Market announcement, Square tersely informs us that “sellers can post items directly to Twitter for their followers to discover and share”. The posting is done via tweets. But there is a lot more to be said about it. As others have already pointed out, Twitter’s “product card” feature, through which Square users’ sales items are posted on the micro blog, turns Twitter into a product catalog, but one that is free for sellers.

Twitter’s product cards look very similar to the listings on Square Market. As Twitter tells us (and as you can see below), they are “designed to showcase your products via an image, a description, and allow you to highlight two other key details about your product”.

Now, it should be said that Twitter’s product cards are available for anyone to use, not just Square, but Jack Dorsey clearly must have had both of his companies’ in mind when the feature was being developed. I think that this statement of his is quite revealing:

We don’t have to brand it explicitly. It’s all about the people using it. Both Twitter and Square have been really great at diminishing their brands in favor of the people using them.

In fact, I’m sure that Dorsey would be perfectly happy if Market’s users advertise their items on other platforms — Facebook, Pinterest and Google Plus come to mind — as long as the owners of these platforms allow for the sales themselves to be processed by Square. Remember, unlike eBay, Square makes money exclusively from charging payment processing fees, not product listing fees.

But should we believe Dorsey when he says that it is all about people using the service? Let’s imagine that, say, Pinterest creates something similar to Twitter’s product cards, which allow Square Market users to list their items for sale on the photo sharing website, much as they would do on the micro blog. However, let’s also imagine that whenever a consumer clicks on the “Buy” button, she is not taken to the seller’s Square Market store, but instead the transaction is completed on Pinterest and, this is the really important part, the photo sharing site collects the payment processing fee. In that scenario Square gets precisely nothing out of the deal. Do you think that, if that were the case, Dorsey would still be telling us that all that matters is for people to use the service? I doubt it. And I also doubt that Facebook, Pinterest or Google would allow such transactions to be completed anywhere but on their websites. However, whereas Square clearly benefits from Twitter’s product cards, it should be reiterated that there is nothing wrong with that — after all, the feature is available on the same terms to anyone who may want to use it.

The Takeaway

I think that Market’s biggest advantage is that it builds on already existing relationships. People and very small businesses, which are already using Square to take credit card payments, now have the option of also selling their merchandise online, without having to expend any additional money or efforts. Yes, they had options before, but for the vast majority of Square users a traditional e-commerce website is simply out of the question — too expensive and complicated to maintain — and even an eBay listing costs some money and takes time to manage. The downside for Square is that the processing volume of the average Market user is likely to be very tiny, as anyone whose business size justifies it will still prefer to maintain a dedicated e-commerce website. Yet, for Jack Dorsey and company it was still worth doing it, as the expense is negligible and at any rate more than justified by the volumes of new data Square will be collecting about its merchants and use to further improve its offerings.

Image credit: Square.

How does it compare to Etsy?