Feeding the Student Loan Black Hole

Bloomberg’s Peter Coy makes a great point in his analysis of the latest student debt data released by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in its Household Debt and Credit quarterly report earlier this week: the huge growth of the overall volume of student debt in the U.S. and the rapidly rising delinquency rate on these loans are direct results of a government policy to give student loans to everyone who wants them, irrespective of the debtors’ ability to repay them. Small wonder then that 85 percent of the outstanding student debt is owed to the government.

Somewhat perplexingly, though, having laid out the facts, Coy takes the easy way out and merely contents himself with making the observation that, by extending credit to vast numbers of people unlikely to pay it back, the federal government has set itself up for huge losses. Well, as Coy surely knows, policy makers fully realize that fact. As he says, the federal student loan programs are designed to give everyone the chance to get a college degree. It’s an admirable goal, to be sure, but the question is whether this is the way to achieve it. Well, it seems to me that, for several years now, the data have been strongly indicating that the answer is “no”. Let’s look at the numbers.

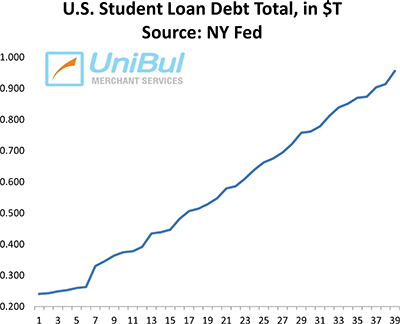

The Rise of Student Debt

The total amount of U.S. student debt has increased fourfold in the past decade — from $241 billion at the end of the first quarter of 2003 to $956 billion at the end of the third quarter of this year. Here is the chart:

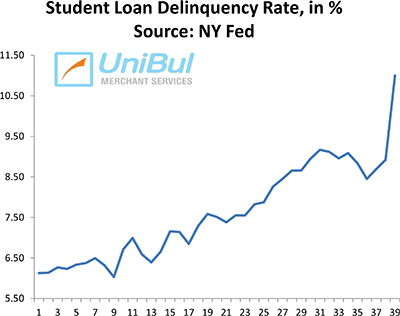

During the same period, the student loan delinquency rate has increased by 80 percent — from 6.13 percent to 11 percent. Here is the chart:

What makes the relentless rise of the delinquency rate even more significant is the fact that the government is doing its best to keep it in check. As Coy says:

Borrowers who are unemployed, in the military, or back in school can ask for up to three years or full or partial deferment on repayment of a federal loan. For those who have a job but don’t earn enough to cover the monthly payment, there are six options: graduated repayment, extended repayment, income-based repayment, income-contingent repayment, income-sensitive repayment, and pay-as-you-earn repayment. In other words, the federal government will do just about anything to keep borrowers from giving up and walking away completely.

Yet, at some point your student loan does become due and has to be repaid. Whether you can pay it back or not, you cannot escape from it. And “walking away” is not exactly a solution to the problem. Coy does a good job at describing the consequences of not repaying your student loan:

Defaulting is “like a trip through hell with no light at the end of tunnel,” says Kantrowitz. The federal government can garnish up to 15 percent of a borrower’s wages, Social Security disability, and Social Security retirement income without a court order. Unlike other debt, student loans can’t be discharged in bankruptcy. Collection charges of up to 20 percent can be skimmed off the top of payments — enough to turn a 10-year loan into a 19-year loan. To say nothing of the lasting damage to a borrower’s credit score, which will make it hard or impossible to get a credit card, auto loan, or mortgage.

As I said, it’s not a pretty picture.

Spinning Down a Black Hole

And yet, the government keeps lending to anyone who asks for a loan. Coy:

The federal government, which holds 85 percent of outstanding student debt, doesn’t make loans to students based on their ability to repay them. That may sound crazy, but it is designed to ensure that students of all backgrounds and income levels get a shot at a college degree.

I can’t see any sense in such a policy. By extending credit to students unlikely to complete their education, the government is not only not helping these borrowers, as they will eventually have to enter the workforce without a college degree and with few prospects of a well-paying job, but it is burdening them with huge amounts of debt that cannot even be discharged in bankruptcy. Oh, and as a side effect, this unlimited supply of student loans helps push college costs ever higher. Saying that the system is unsustainable in its present state would be putting it mildly. The government is inflating a bubble that will inevitably burst, with potentially disastrous consequences not only for the student loan system, but for the economy as a whole.

The Takeaway

The laws of economics will always be served and the day of reckoning is approaching. The extension of credit to people who can’t reasonably be expected to pay it back, with interest, makes no sense at all, for anyone involved in the transaction and whatever the stated purpose. That practice will eventually have to be abandoned and regular underwriting procedures instituted. The only question is how much damage will be done before the inevitable happens.

Image credit: Alaskadispatch.com.

The growing student loan bubble is a huge concern, especially for people who are just entering college. With the cost of student tuition continuing to rise, the necessity for families to borrow is also rising. Some people are starting to look outside of the federal aid that is offered by going into the private sector. The options found there aren?ÇÖt much better and some of them even resemble the variable rate loans from the housing crisis. Loan underwriters need to take accountability and make sure that the loans being offered will not lead to another industry crash. New start ups in the student loan industry may be on to something as well. CommonBond is a program that connects student borrowers with alumni investors to offer lower rates. Additionally, it provides a network to help students find jobs once they have completed their education. This seems like a good model that could have a positive impact, especially in today?ÇÖs economy.