How to Clone a Smart Credit Card

The EMV technology was introduced a decade ago to make it impossible for criminals to clone our credit cards and is now the standard in most of Europe, Asia and elsewhere. According to all reports that I’ve seen, the strategy has succeeded and credit card fraud levels are now way down in all countries that have adopted the new technology.

But is it possible that the criminals have just not had the time or desire to adjust to the new system and to fully explore its vulnerabilities? After all, studies have shown that following a switch to EMV in a given country, the fraudsters have simply shifted their attention to non-chip transactions (e-commerce would be one example) or to other countries (e.g. the U.S.). However, now that the U.S. — the world’s biggest credit card market — has gradually begun the transition to EMV, the criminals may finally be forced to take a harder look into the new technology and, according to a recent paper published by four University of Cambridge researchers, there are flaws to be discovered there and exploited.

The Issue with EMV

The researchers have looked into the smart card adoption process in Europe and have found that it has been far from smooth:

EMV is the main protocol used worldwide for card payments, being near universal in Europe, in the process of adoption in Asia, and in its early stages in North America. It has been deployed for ten years and over a billion cards are in issue. Yet it is only now starting to come under proper scrutiny from academics, media and industry alike. Again and again, customers have complained of fraud and been told by the banks that as EMV is secure, they must be mistaken or lying when they dispute card transactions. Again and again, the banks have turned out to be wrong. One vulnerability after another has been discovered and exploited by criminals, and it has mostly been left to independent security researchers to find out what’s happening and publicise it.

The authors stop short of passing judgment on whether the issuers have genuinely believed in the inviolability of the newly-adopted card payment system or have just been taking advantage of the new technology’s sterling reputation. However, they do cite one court case, in which the plaintiff had sued an unnamed bank for a refund of a transaction he claimed was fraudulent. The judge ruled in the defendant’s favor, even though the bank had destroyed the log files, in direct violation of Visa’s rules. I can’t help but wonder why the issuer would risk being penalized by the card networks and destroy the transaction files and I can’t think of any reason, other than hiding the evidence that the transaction was indeed fraudulent.

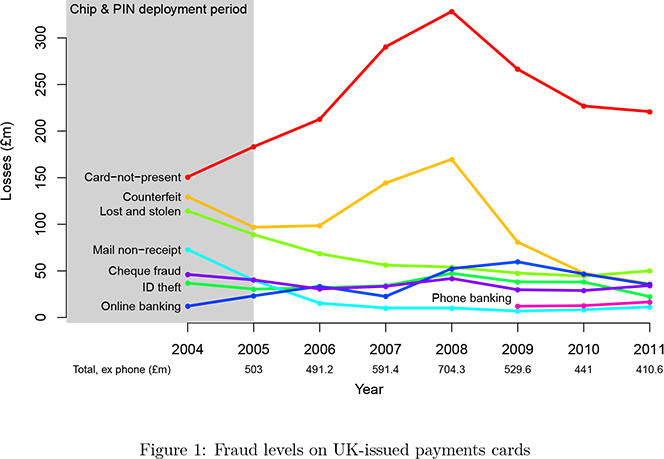

Yet, even if you don’t count such unproved cases, credit card fraud still went up in the first few years following the EMV adoption. Here is the chart for the U.K., as presented in the paper:

Eventually, fraud levels were brought down

through improvements to back-end fraud detection mechanisms which reject suspicious transactions; by more aggressive tactics towards customers who dispute transactions; and by reducing the number of UK ATMs that accept “fallback” magnetic-strip transactions on EMV-issued cards.

Chip and Skim: Cloning EMV Cards

The researchers have identified a vulnerability that exposes EMV-compatible point-of-sale (POS) terminals and ATMs to what they call a “pre-play” attack:

Payment cards contain a chip so they can execute an authentication protocol. This protocol requires point-of-sale (POS) terminals or ATMs to generate a nonce, called the unpredictable number, for each transaction to ensure it is fresh. We have discovered that some EMV implementers have merely used counters, timestamps or home-grown algorithms to supply this number. This exposes them to a “pre-play” attack which is indistinguishable from card cloning from the standpoint of the logs available to the card-issuing bank, and can be carried out even if it is impossible to clone a card physically (in the sense of extracting the key material and loading it into another card). Card cloning is the very type of fraud that EMV was supposed to prevent.

The criminal wouldn’t need to physically clone the card, because, by inserting a device between the merchant and its acquiring bank, he could intersect and modify a transaction en route to the acquirer.

The Takeaway

The paper doesn’t offer any specific measures for shoring up the EMV technology’s defenses against such “pre-play” types of fraud. Instead, the researchers are urging for more regulation, because “not even the largest card-issuing bank or acquirer or scheme operator has the power to fix a problem unilaterally”. I don’t think that more regulation is what’s needed here. It is in Visa’s and MasterCard’s best interest to enforce the needed changes and they are more than capable to do that. I expect that that the card networks will take action sometime soon, before the criminals manage to exploit the vulnerability.

Image credit: Procuria.net.

Chip-based cards are not nearly as secure as their proponents make them sound. It’s going to take years until their security can be improved.

You put the credit card in the chip reader backwards

EMV is really not secure with a simple software like EMV Reader Writer Software v8.6 any-own can clone a EMV Credit card and use it like the original one

how is that posible ? EMV Reader Writer Software v8.6 ?????

Chip-based cards are not nearly as secure !they are really not safe a simple software like EMV Reader Writer Software v8.6 can clone any emv chip soo….

there is also a software emv sdk http://www.emv-sdk.com that will allow anyone to spoof the arqc key generate a icvv at each transaction,so emv are not secure as the bank pretend

??Poor people have a whole mythology about money. There is a whole set of delusions associated with superstitions and myths about money. There are a lot of proverbs about money, including religious ones. Sometimes I think that all such things are invented by wealthier people for less wealthy people.

What’s the difference between poor and rich?

Wealth is only the difference between people from one person and another, and the difference is in many aspects. The common difference is the amount of property and money that a person can dispose of. And if we give everyone an equal amount of property, the poor and rich will disappear for a certain period of time.

But…

If you’re an alcoholic, you’ll become an alcoholic again, even after a miraculous enrichment with trading. If you’re a gambler, you’ll lose your entire deposit one way or another. If you’re a lazy ass – you’ll forget all about it and go back to idling.

Yeah, trading can make almost anyone rich. But it’s up to the man to keep him there by fighting the inner demons.

Clone ?prices?

1k$ balance costs 200$ btc

3k$ balance costs 400$ btc

5k$ balance costs 600$ btc

10k$ balance costs 1k$ btc

15k$ balance costs 1.5k$ btc

20k$ balance costs 2k$ btc

You don’t need no Pc or any hacking knowledge for this?

All you need is your Phone ? to Dm me for your CCC???….. 4602078574

Wait a darn minute…

That is smart dude