Where Is My Debit Discount?

The proponents of the legislation that reduced the fees retailers pay for accepting debit cards promised that such a reform would lead to lower retail prices. The reform, known as the Durbin Amendment, went into effect on 1 October 2011, but Martha C. White of Time Magazine can’t see the savings. What she does see instead are higher bank fees.

White is not the first one to make this observation. We have written about the Durbin Amendment’s negative side effects on this blog many, many times before. But if the reform didn’t result in lower retail prices, where did the money go? After all, the lowering of the debit interchange fees from an average of $0.43 to $0.24 per transaction has reduced the card issuers’ aggregate annual revenue by billions of dollars ($8 billion, according to a CardHub.com estimate cited by White). However, locating the whereabouts of the missing billions proves to be a daunting task and White eventually gives up on it, concluding that “about the only thing everyone agrees on is that customers are losing out while these respective industries [retail and banking] battle over swipe fees.”

Well, I think that White may have given up a bit too easily on this one. There are only two places where the missing billions may be hiding: the merchants and their processors. Let me elaborate.

What Is Interchange?

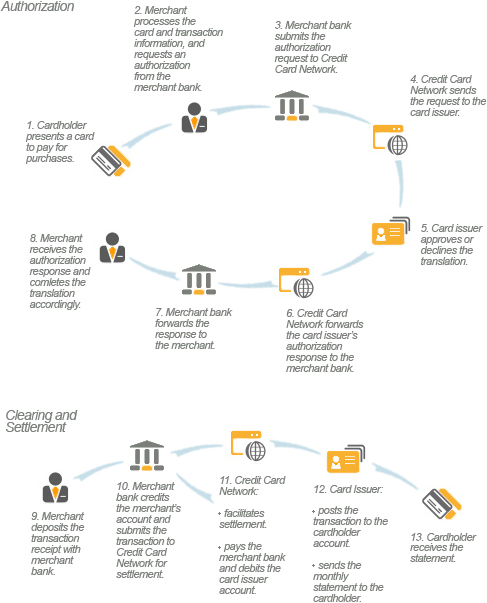

In order for us to locate our elusive target, we first need to understand exactly what interchange is. So interchange is the fee which a card issuer collects for every transaction that involves one of its payment cards (credit, debit or prepaid). The interchange fee is paid by the processor of the transaction, which then collects it from the merchant which accepted the card for payment. The whole process is facilitated by the credit card network (Visa or MasterCard) whose logo is imprinted on the card. Here is a visual representation of the process:

By the way, the “swipe fee” label that is frequently applied to the interchange fees is really unhelpful. These fees are charged for both swiped (face-to-face) and non-swiped (telephone or e-commerce) transactions.

How Merchants Pay Their Transaction Fees

Now that we know what interchange is, let’s take a look at how it is collected from the merchants. As illustrated in the diagram above, the merchant does not transact directly with the issuer. The processing bank (or merchant bank) is the merchant’s link to the payment card system and is the entity responsible for the settlement and funding of the merchant’s transactions. It is also the entity that collects the interchange fees from the merchant. However, the interchange makes up only a portion of the total amount of the fees collected by the processor. The rest is comprised of the fees which the processor itself charges for its services. And here is where it gets tricky.

The only way that a merchant would have directly benefited from the lowering of the debit interchange fees would be if it had signed up for an interchange-plus pricing model with its processor. In this pricing structure, the processor’s fees are charged independently from the interchange fees, so any lowering of the latter by any amount would result in a saving for the merchant by the same amount. Let me give you an example. Suppose that a merchant is charged a transaction rate of 0.50 percent above the interchange. Here is what this merchant would be charged for a debit transaction in the amount of $100 before and after the Durbin reform.

|

Transaction Amount: $100 |

Merchant Fees if Pricing Structure is Interchange + 0.50% |

|

Pre-Durbin Interchange: 0.95% + $0.20 |

$1.65 |

|

Post-Durbin Interchange: 0.05% + $0.22 |

$0.77 |

So in our hypothetical example (I’ve used the pre-Durbin rate of Visa’s “CPS/Retail Debit — All Other” interchange category), the merchant pockets the entire saving (all $0.88 of it) afforded by the interchange reform.

However, in any other type of merchant pricing, the interchange rate is incorporated into the aggregate processing rate, which is unaffected by the Durbin Amendment and in this case the saving would be pocketed by the merchant. Here is the same example, but this time the transaction rate is a flat 1.45 percent plus $0.25:

|

Transaction Amount: $100 |

Merchant Fees if Pricing Structure is 1.45% + $0.20 |

|

Pre-Durbin Interchange: 0.95% + $0.20 |

$1.65 |

|

Post-Durbin Interchange: 0.05% + $0.22 |

$1.65 |

As you see, in this scenario the lowering of the interchange rate has absolutely no impact on the merchant’s processing cost, but it increases the processor’s profit.

The Takeaway

So the different pricing structures used by the payment processors are the main reason why Martha White and others are having difficulties tracking down the billions lost by the card issuers in the wake of the interchange reform. And yet, there are only two participants in the transaction process that may have collected the elusive fees: the processors themselves and the merchants.

But keep in mind that all of the big retailers’ payment processing accounts are set up using interchange-plus pricing. Big-box retailers employ armies of accountants who have long ago figured out that interchange-plus is by far the best pricing model, even as their smaller competitors are having a huge problem wrapping their minds around it (trust me, I’ve tried explaining what interchange is and how it works many, many times with astonishingly little success). The bottom line is that the big retail guys are paying much less in debit transaction fees than they used to. So where is my promised discount?

Image credit: Etsystatic.com.

The Durbin Amendment is as good an example as we can have that government intervention should be kept to a minimum. They totally dropped the ball on this one, although they’ll never admit it.

What I want to know is how the Fed calculated that the debit card fees should be capped at 24 cents. Why not 15 cents or 35 cents? I’ve never seen a single explanation for their decision. It seems to me that they were not sure what they were supposed to do and made a mess of this thing.

Durbin seems to believe that banks are non-profit organizations, rather than for-profit businesses and there is not much we can do about that. But in the real world banks exist to make money for their shareholders and to do that they have to charge money for the services they provide. They have to comply with all kinds of costly requirements, which further adds to their costs and these requirements are increasing all the time. The banks cannot be expected just swallow these additional fees. If they did, they’d go bankrupt.

Once more we are haunted by the unintended consequences of a totally misguided and poorly written legislation. Why exactly does Durbin believe that he is smarter than everyone else and knows best what the interchange should be. Keep in mind that he keeps telling everyone who would listen that the Fed should have place a lower limit on these fees.

We accept credit cards and PIN debit in my convenience store, but our merchant services provider has raised rates again and I’m not sure that it’s worth it and may go back to cash only. The customers won’t like it but that’s what we may have to do.

Scott,

All you have to do is switch to another service provider, there is a ton of them out there to choose from. Just because one company is increasing its pricing doesn’t mean that the government should get involved and set the “right” fees.

It’s not the debit fee limit that has caused “unintended consequences.” It’s the banks and all of their affiliates that insert themselves between the merchants and their customers that are to blame. They want to get as big a cut as they can get away with and will not easily back off. So the fee limit is a step in the right direction and the same thing should be done for credit cards.

Jeff,

If a limit on debit interchange fees did so much damage in the form of higher bank fees elsewhere, can’t you imagine the devastation that would result from a cap on credit interchange? This is not about greed or anything like it, it’s about charging a fee for a service provided. And it’s not like merchants are forced to accept credit cards. They don’t have to if they don’t want to.

I’m all for the debit fee limit. Yes, the banks are trying to get around the rules and hike fees in other places, but that should not be allowed. And no, this is not just business as usual: you charge a reasonable fee for the service you provide. These fees were way too high and were hurting the small retailers.

What I don’t get is if what the Durbin Amendment is about bringing debit fees to reasonable levels, why did it exempt the small banks? They continue to charge as much as they used to before the limit was passed. Am I the only one who sees a double standard at play here?

The real problem with the Durbin Amendment is that tries to decide what the cost of a service should be, which the government has no business doing. If they can decide on the level of debit interchange, why wouldn’t they set the price of a cup of coffee? What’s the difference? Once they get involved in setting prices, this cannot be isolated to a certain industry and there is no end to it.

The merchants are still complaining about high debit fees, even after they were reduced to 24 cents. Well, if they don’t like them they don’t have take cards. What is the problem here? If I think that Starbucks’ lattes are too expensive, I don’t buy them. I don’t go in the store and start arguing with the manager that he has to lower the price of its coffee.

Andrew,

Setting the level of interchange fees is a bit more complex of a thing than setting the price of a Starbucks coffee. If you don’t like paying $3 for a latte, you can go to the 7/11 next door, but you can’t do that with credit cards where Visa and MasterCard have a duopoly of the market. So a slight intervention like this one was needed and will not bring destruction.

Bill, this is not a “slight intervention.” Nothing like it. Debit interchange fees were reduced by 45%, not by 5% or 10%. Imagine getting Starbucks, to use your example, to lower the cost of its latte from $3 to $1.65. I know you would like it, but I’m not sure there will still be a Starbucks around to serve it to you.

Banks will just have to accept lower debit interchange revenue, just as we had to accept living through years of misery that followed the financial crisis they caused and there is no end in sight to it. And if they don’t like it, too bad.

We are all paying the price of this thing. Free checking is gone and overdraft fees are up and no retailer that I know of has reduced prices art all, which was the whole point. Great job Dick Durbin!

Great comment John.

Look at the marvelous job they did in the health insurance industry, prices are going UP not down. Where does it stop? Why not regulate taxi fares and plane tickets? Hell, why don’t we just issue a national mandate that NO business can mark up ANY product or service beyond a certain percent or cost? I’m sure all the government tit suckers would rejoice at that… and it will be at that point we all realize what has happened, that the other foot has finally stepped into the murky waters of socialism and there will be no return absent of a revolution.